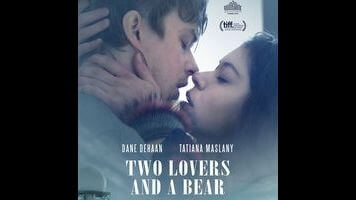

This magical melodrama has Two Lovers And A Bear, and not much else

Set in the snowy, isolated northernmost reaches of Canada, Two Lovers And A Bear provides only a brief glimpse of any living organism not included in its title. Both Roman (Dane DeHaan) and Lucy (Tatiana Maslany) deliberately came to the small outpost called Apex in order to flee unpleasantness back in civilization, and the movie proves to be a battle between their dueling buried traumas. Lucy, who drives a cab (even though snowmobiles seem to be the region’s primary vehicle most of the time), initially seems the more stable of the two, albeit prone to panic attacks in response to an unidentified, threatening male figure who repeatedly appears out of nowhere. Indeed, Lucy has even applied to a university somewhere back in the larger world, intending to study biology. When she’s accepted, Roman, who says he’d rather kill himself than go back to wherever he came from, abruptly ends their relationship, leading to a series of screaming fits and drunken rages that ultimately land Roman in a rehab clinic.

All of this is just belabored setup for the film’s main journey, which sees the reunited couple set out for civilization together on snowmobiles. Director Kim Nguyen (War Witch), who also wrote the screenplay (based on an idea by Louis Grenier), was clearly inspired by the romantic notion of two vulnerable people in a vast frozen landscape, with nothing to rely on except each other. They find love, you might say, in a hopeless place, though their relationship seems to be defined entirely by sex and shared torment. Both actors are burdened with conveying how deeply haunted these characters are by their pasts; DeHaan gets the showy, choked monologue recounting a horrible episode he can never forget, while Maslany, who made her name playing wildly divergent clones on Orphan Black, gets stuck here toggling between levelheaded and batshit insane. By the time Roman and Lucy seek shelter from a storm in an abandoned military bunker, Two Lovers And A Bear has turned into a horror film in which backstory is the monster.

What about the bear, though? Oh, right: There’s also a talking polar bear, who speaks in the voice of venerable Canadian actor Gordon Pinsent (best known in the U.S. from Sarah Polley’s Away From Her). This magical-realist element gets introduced early, and Nguyen makes a point of establishing that the bear itself is real—other people (including Lucy) see it, though only Roman and the audience hear its voice. “I can talk to bears,” Roman explains, and that’s that, basically. Nothing significant comes of the bear’s recurring presence, however—it just shambles up to Roman at key moments to dispense ursine wisdom (and demand fish), and seems to represent the beyond in some conveniently vague way. It’s the bear who counsels Roman on what he’ll need to do in order to finally vanquish Lucy’s personal demon, leading to an ending that’s clearly intended to be tragically beautiful, but which mostly just suggests that these damaged young people badly needed psychiatric help. Preferably from somebody who’s bipedal.