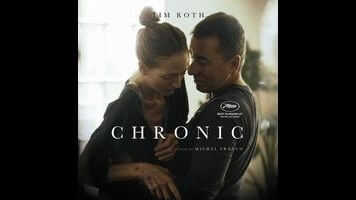

This mysterious Tim Roth drama has a Chronic case of ambiguity

Most film students learn early on about the Kuleshov effect, which demonstrates how much our interpretation of a neutral image is influenced by whatever image precedes it. The same blank facial expression that’s perceived as “hungry” when it follows a shot of soup, for example, becomes “sad” when it follows a shot of a little girl in a coffin. Chronic, the first English-language feature by Mexican director Michel Franco (Daniel And Ana, After Lucia), employs the Kuleshov effect on a grander scale, freighting a whole lot of ostensibly neutral scenes with tension that’s derived from other, tangentially related scenes. The whole movie is an exercise in ambiguity, designed to engender suspicion about activities that would ordinarily seem utterly benign, and that might very well be utterly benign. When Chronic premiered at Cannes in 2015 (where it unexpectedly won Best Screenplay), one tweet waggishly retitled it Caring Is Creepy, and it really does play, for better and worse, like a lengthy exploration of that Shins song’s thesis.

The film’s equivalent of the bowl of soup or the dead girl is its voyeuristic opening scene, in which a man named David (Tim Roth) sits parked outside a suburban house and then stealthily follows a young woman (Sarah Sutherland) who emerges from it, for reasons unknown. Later, we see him repeatedly Facebook-stalking the same woman, strengthening the impression that he’s a deviant of some sort. The vast majority of Chronic, however, simply observes David at work as a hospice nurse. He tends to one patient at a time (turnover is dismayingly speedy), and appears to be compassionately devoted to making their final days as painless as possible. Our knowledge of how David spends his off hours can’t help but intrude upon long, uninflected shots of him soaping up his nude patients in the shower. Is he getting off on this in some way? One dying man insists that David watch porn with him, and it’s hard to know whether David’s willingness to do so demonstrates that he’s kind and understanding, or that he’s a total perv with no business in this line of work. When he’s sued for sexual harassment, it’s unclear whether that’s just.

Roth does a superb job of making David unreadable without turning him into an automaton, especially in some oddly disturbing off-duty scenes that see him casually incorporate details of his patients’ lives into his own personal history. (Talking with strangers at a bar, he speaks of one recently deceased patient as if she’d been his wife of many years; when he’s caring for an architect, he pretends to be one.) But his efforts are undermined by Franco’s emphasis on the stalking behavior, which makes the character far too overtly menacing. A little inappropriate behavior would have gone a long way. Chronic also eventually serves up a bathetic backstory for the character, needlessly “explaining” his dedication to his work. Worst of all, the film ends on a note so randomly jarring that the audience at the film’s Cannes premiere burst into mocking laughter, which was clearly not the intended reaction. This conclusion feels like such a fuck-you, directed at the viewer, that it retroactively recodes the entire movie as a sick shaggy-dog joke. Is there a film-school term for an image that influences the preceding image? If not, call it the Franco effect.