Elagabalus was also a prostitute, working in taverns, brothels, and even the palace. He bragged that he out-earned other prostitutes, and according to later Roman historian Cassius Dio, “he had numerous agents who sought out those who could best please him by their foulness.” In and out of the brothel, Elagabalus would “paint his eyes, depilate his body hair and wear wigs” to appear more feminine, and preferred to be called a lady and not a lord. Cassius Dio wrote that “Elagabalus delighted in being called Hierocles’ mistress, wife, and queen.” He also “offered vast sums to any physician who could provide him with a vagina,” which may have made Elagabalus the first person on record as seeking out gender-reassignment surgery.

(A note on pronouns: While it’s possible Elagabalus was a trans woman, we only have speculation based on centuries-old gossip to go on, so absent stronger evidence one way or the other, we’ll continue to use the emperor’s assigned-at-birth gender, as the Wikipedia article does.)

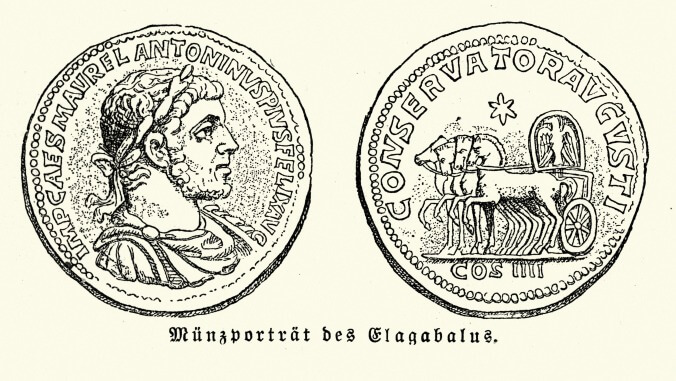

Strangest fact: His name wasn’t Elagabalus. Like the Pope, the emperor often assumed a new name upon taking the throne; Elagabalus’ was Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus. His given name was likely Sextus Varius Avitus Bassianus, although the historical record doesn’t seem sure. The name Elagabalus came from a Syrian sun god who was folded into the Roman pantheon. Our emperor was a priest of Elagabalus as a child, and as emperor replaced Jupiter with Elagabalus as the head of the pantheon of gods (to much consternation from the Roman faithful), and presided over religious ceremonies in his honor. Marcus Aurelius Severus Antoninus was only referred to as Elagabalus after his death, most likely to differentiate him from Caracalla, three emperors previous, who also went by those same four names.

Thing we were happiest to learn: Women’s rights took a small step forward under Elagabalus. Powerful women in Rome could usually only assert power indirectly, and Elagabalus was put in power through his grandmother’s influence. When Caracalla was assassinated, he was replaced by the head of the Praetorian Guard, Marcus Opellius Macrinus, but Caracallas’ aunt (and Elagabalus’ grandmother), Julia Maesa, convinced the army’s Third Legion to revolt and put her grandson on the throne at age 14. Once in power, Elagabalus gave senatorial titles to both his mother and grandmother (women had previously never been allowed in the Senate chamber), and both can be found on Roman coins, rare for women in any era of Rome.

Thing we were unhappiest to learn: Elagabalus’ reign didn’t last. After less than five scandalous years, Elagabalus had exhausted the patience of the real power behind the throne. The Praetorian Guard disapproved of his sexual antics, particularly his relationship with his chariot-driver husband Hierocles, while Maesa realized her grandson had no popular support and hung both him and her daughter out to dry.

Maesa pushed Elagabalus to appoint his cousin, Severus Alexander, as his heir and co-consul. Elagabalus quickly realized the Praetorians preferred Alexander, and after several failed assassination attempts, Elagabalus had to be content to strip his cousin of his titles and revoke his citizenship. The Praetorian Guard demanded to see the two cousins in their camp. When they, along with Elagabalus’ mother, appeared, the Praetorians cheered Alexander and ignored the emperor. Enraged, Elagabalus ordered the arrest and execution of the insubordinate soldiers. Instead, the guards killed him and his mother. We return to Cassius Dio: “[T]heir heads were cut off and their bodies, after being stripped naked, were first dragged all over the city, and then the mother’s body was cast aside somewhere or other, while his was thrown into the Tiber.” Hierocles and several of Elagabalus’ other associates were killed soon after.

Also noteworthy: Some more recent historians question the narrative of Elagabalus as an oversexed incompetent. After his death, Elagabalus suffered damnatio memoriae—his name was erased from public records, and statues of him were re-carved to resemble Severus Alexander. As a result, much of what was written about Elagabalus came from his enemies, and has therefore come under question. Martijn Icks’ 2008 book Images Of Elagabalus argues that it was Elagabalus upending the Roman religion, not his sexual exploits, that turned the Roman elites against him. Leonardo de Arrizabalaga y Prado’s The Emperor Elagabalus: Fact Or Fiction? from the same year suggests he was merely a pawn in his grandmother’s power struggles, and the more salacious stories were part of a campaign of character assassination, which quickly followed his more literal assassination.

Further down the Wormhole: We mention Cassius Dio several times, because as historians go, he’s the closest thing we have to a primary source on Elagabalus. Cassius Dio was his contemporary, and while he wasn’t in Rome during much of the young emperor’s reign, he had easy access to eyewitness accounts. He also served as consul under Severus Alexander, so his accounts may contain a bit of bias, but in general, Dio is a terrific source, as his book Roman History spans nearly a thousand years, starting with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. A hero of the Trojan War (second cousin to Hector and Paris) mentioned in The Iliad, Aeneas is a revered figure in both Greek and Roman mythology.

While Aeneas may have been an historical figure, most of the stories about him are mythological—Aphrodite and Apollo frequently intervene on his behalf, and Poseidon rescues him after an assault by Achilles. The Iliad’s main character, and the greatest of Greece’s warriors, Achilles also blurs myth and history, and as with Aeneas, myth wins out, as Achilles is most famous for his heel—his only vulnerable spot, after being dipped in the River Styx and granted magical invulnerability. The Iliad refers to Achilles as “the brightest star in the sky.” That star would be Sirius, visible from almost everywhere in the world, apart from the very northernmost latitudes. We’ll beat the summer heat by visiting the list of northernmost settlements next week.