This week, and maybe any other, the terrorist-attack docudrama Hotel Mumbai is a grueling watch

Hotel Mumbai, a brutally realistic dramatization of the 2008 Mumbai terrorist attacks, can’t help but inspire some thorny ethical questions. It arrives in theaters exactly one week after the nightmare in Christchurch, New Zealand—apparently, distributors are now resigned to every date on the calendar being in close proximity to a mass shooting, and won’t bother to postpone release out of sensitivity. Many people have watched the live-streamed video recording of that massacre, either because they’re sadistic racist ghouls themselves or (more commonly, in all likelihood) out of morbid curiosity. Others find the very idea of doing so distasteful, if not obscene. What if someone were to meticulously re-create that footage, though, using actors and squibs? Still horrible, or acceptable? Now what if there were no footage, but a filmmaker interviewed the survivors and attempted to accurately depict what the massacre looked like? Would that qualify as entertainment? Exploitation? Is it worth honoring the bravery and selflessness of those who fought back or attempted to save others if you’re simultaneously treating real-life victims as bullet-riddled extras? There are no easy answers, but one thing’s for sure: If the thought of seeing a lot of people get murdered with automatic weapons at close range makes you queasy right now, Hotel Mumbai is not a film you want to go anywhere near. Few slasher movies have such a high, graphic body count.

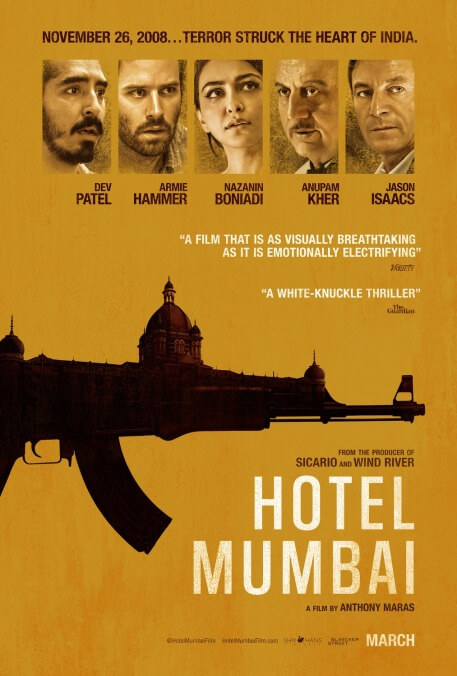

As its title suggests, the film concentrates primarily on events at the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel, though there are also brief depictions of simultaneous, equally horrific attacks at a railway station and a café. Dialogue among the terrorists identifies them as Islamic radicals who consider their victims infidels (another good reason not to release it at this particular moment, arguably), but anyone curious about the group’s history, ideology, goals, or even geographical origin (Pakistan), will have to research those subjects on their own. Hotel Mumbai scrupulously avoids providing any information that the characters on screen wouldn’t know; so far as the Taj Mahal Palace’s staff and guests are concerned, several young men just walk in and start shooting everyone in sight, for reasons unknown and, for the moment, unimportant. Among those who manage to stay alive and hidden, at least for a while, are the hotel’s head chef (Anupam Kher), one of its waiters (Dev Patel), a married couple (Armie Hammer and Nazanin Boniadi), the nanny who’s caring for their baby (Tilda Cobham-Hervey), and an obnoxious Russian businessman (Jason Isaacs).

Viewers who sit through the closing credits will see a standard disclaimer noting that while the film is based on actual events, some characters are composites of several individuals, and various details have been altered for dramatic purposes. Some aspects of Hotel Mumbai do indeed feel Hollywood-processed (though it’s actually an Australian production), from various nick-of-time escapes to the matter of which characters can be executed before our eyes and which ones, like the nanny holding the baby, are clearly safe because their slaughter would just be too deeply upsetting. At the same time, though, director Anthony Maras, who cowrote the screenplay with John Collee, refuses to sugarcoat the sheer horror of what happened. The terrorists killed 31 people at the hotel (165 total across 12 locations), and it feels like we see every single one of those deaths—slowly, methodically, with little left to the imagination. In real life, the attack lasted three days; the movie compresses it to roughly 12 hours, but that’s long enough for the carnage to become numbing. People are still getting their brains blown out in the last few minutes.

Maras has said that he made Hotel Mumbai in order to pay tribute to the Taj Mahal Palace’s employees, many of whom heroically chose to remain in the building and attempt to save guests rather than flee. That heroism is represented on screen, but often in a hokey way: Chef Oberoi, for example, gathers the staff and delivers a motivational speech familiar from countless Westerns—the whole “If any of you want to back out now, no hard feelings” spiel. Likewise, a scene in which Patel’s Sikh waiter explains the religious significance of his turban to a foreigner, offering to remove it if that will make her less frightened of him, comes across as a didactic contrivance. And all of these moments honoring the victims wind up subsumed by the amount of time spent observing the terrorists as they stalk their prey, communicate with their handlers back in Country To Be Named Later, tearfully call their families asking whether said handlers have sent the money they promised, etc.

The recent quasi-documentary Tower, which uses rotoscoped animation to re-create Charles Whitman’s 1966 sniper attack at the University Of Texas At Austin, demonstrated that it’s possible to depict a prolonged mass shooting, beat by beat, without inadvertently reducing human beings to mere targets. Maras goes the conventional thriller route, with an extra helping of viciousness and gore, and while he’s done a skillful, professional job—nobody will be bored, certainly—he hasn’t made a strong case for the value of his film’s existence, either as entertainment or homage. Do we gain anything by watching a man spend two hours valiantly attempting to protect his loved ones, only to finally be shot point-blank in the head by someone who thinks of him as subhuman? Perhaps in certain contexts, but not this one.