This week’s most pressing legal issue: Monkey selfies!

We explore some of Wikipedia’s oddities in our 6,181,160-week series, Wiki Wormhole.

This week’s entry: Monkey Selfie Copyright Dispute

What it’s about: Definitely the most consequential legal dispute you’ve read about this week. In 2008, nature photographer David Slater was trying to get up-close photos of endangered Celebes crested macaques in Indonesia. The macaques didn’t trust him to get up close, but he found that if he left his camera on a tripod, the animals would look at their reflection in the lens, and even push the release to take photos. Three years later, he licensed the photos for publication, but when they ended up on Wikipedia, the Wikimedia Foundation argued that Slater couldn’t copyright the images, as they weren’t taken by him. What resulted was the biggest cross-species legal dispute since Yogi Bear’s 1966 indictment for pic-a-nic basket theft.

Biggest controversy: Wikimedia’s argument was that a copyright was held by the creator of an image, which wasn’t Slater—but that animals can’t hold copyrights, so the macaque selfies belonged in the public domain. But there was a third legal position: PETA jumped into the ring, arguing that animals should be able to hold copyrights. By that point (2015), Slater had published a book of monkey selfies, and PETA argued that the macaque who took the photos should receive the royalties, which would then be used to benefit the endangered species (under PETA’s guidance, naturally). A judge threw out that argument, ruling that under U.S. law, a monkey cannot hold a copyright. (An appeals court found that “PETA’s motivations had been to promote their own interests rather than to protect the legal rights of animals.”)

Meanwhile, Slater claims he lost £10,000 in income, as he earned £2,000 in licensing fees the first year the photos were available, but as soon as they appeared on Wikipedia, no one wanted to pay for them. In 2016, he intended to sue Wikipedia, but cried poverty, saying he couldn’t pay a lawyer to pursue the suit. (Slater, who’s British, would also have to travel to the U.S. at his own expense for a trial of indeterminate length, as Wikimedia is an American nonprofit and the issue falls under U.S. copyright law.) So as of this writing, the public domain legal issue is unresolved.

Strangest fact: This is basically the plot of The Bee Movie, in which a human sues on behalf of an animal who wants royalties for their work. Just replace bees with macaques, honey with intellectual property rights, and the human woman who wants to fuck a bee with PETA.

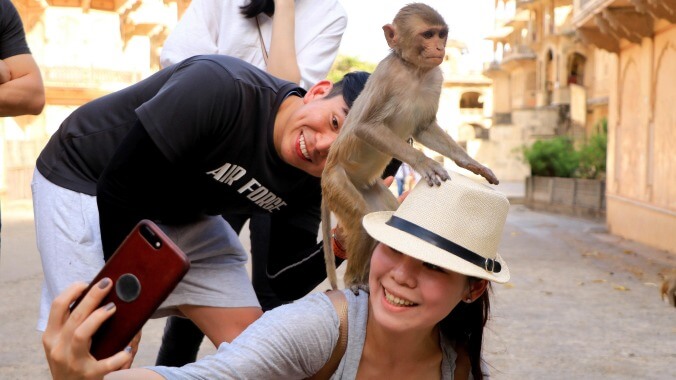

Thing we were happiest to learn: Slater was able to look on the bright side. Besides retaining royalties from his book, Slater also sold the rights to his story to Condé Nast, who want to make a documentary film about the monkey selfie legal dispute. Slater was also “absolutely delighted,” with the photos’ cultural impact. He did succeed in bringing attention to these endangered animals, and may have helped save the species. Locals long considered the crested macaque pests, as they ate crops; the macaques were hunted, despite their endangered status. But since Slater’s photos, the “selfie monkeys” have become a beloved tourist attraction.

Thing we were unhappiest to learn: We still don’t have a resolution on the monkey copyright issue. Intellectual property lawyers (several of whom are quoted here) are split between two arguments: that, as animals can’t hold copyrights, the photos fall into the public domain, or the argument Slater himself made, that he did the bulk of the work to make the photos happen, finding the macaque troop, gaining their trust, setting up the equipment in such a way that the macaques could take the photos, and the monkeys simply pressed the button. The issue won’t be settled definitively until a court rules on it, so we’re hoping resolution comes from the precedent-setting case Best Of Times V. Blurst Of Times.

Also noteworthy: Not only did Wikipedia win the legal dispute because Slater didn’t have the means to fight them, they were kind of dicks about it. The Wikimania 2014 convention adopted the monkey selfie as an unofficial theme, with attendees taking their own selfies in front of a print of the disputed image. Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales was among those taking selfies with the money selfie, which was criticized as “tactless gloating.”

Best link to elsewhere on Wikipedia: One British lawyer suggested that Slater has a legal case based on that country’s rulings on computer-generated art, which argues that a programmer who creates conditions in which a computer can make art can credibly claim authorship of whatever the computer produces. This would also have legal implications on another murky area of intellectual property—animal-made art. Elephants, rabbits, and dolphins have made paintings, with some primate artwork even displayed in museums.

Further Down the Wormhole: The court ruled that PETA was acting out of self-promotion and not genuine concern. Every activist group struggles with striking a proper balance between the two, as well as between appealing to those in power and taking direct action to push for change. “Direct action” is a term for protest, violent or non-violent, that causes enough disruption to force a response, and there’s a long tradition that stretches from Gandhi’s independence movement to the ongoing Black Lives Matter protests.

Some of the most successful direct action in American history were the protests of the Civil Rights Movement, with marches, sit-ins, boycotts, and strikes carried out by everyone from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the NAACP to the United Auto Workers and Brotherhood Of Sleeping Car Porters. The BSCP was the first Black-led labor organization to be welcomed into the AFL, and in the 1910s and ’20s, were involved in another protest movement, the Society For The Prevention Of Calling Sleeping Car Porters “George”. While the SPCSCPG was jokey on the surface, it revealed serious issues underpinning the railway industry.

While the SPCSCPG is a fascinating glimpse at a largely forgotten moment in history, the Wikipedia article is only a few paragraphs. So we’re going to try something new: Instead of doing a deep dive into one Wikipedia article, we’re going to do a bunch of quick hits on short articles that are nonetheless fascinating. We’ll take several short steps further down the wormhole next week.