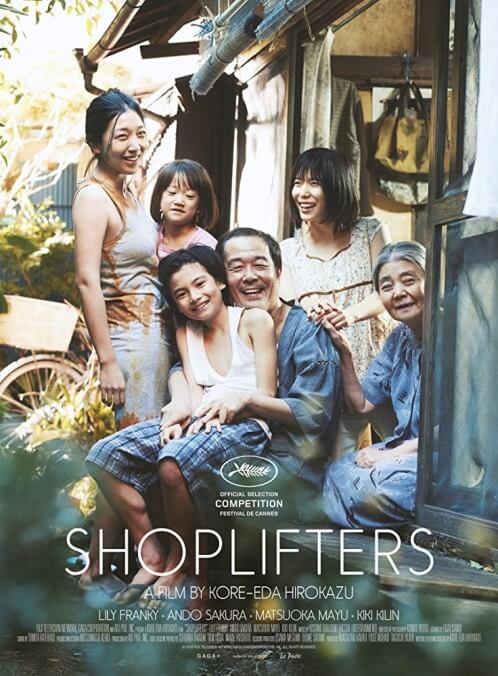

This year’s big Cannes winner, Shoplifters, is an affecting ode to the families we choose

Kids partaking of the ol’ five-finger discount is a common sight in the movies. Sometimes it’s an early indication of serious trouble; more often, minor larceny is merely intended to suggest a character’s rebellious nature. Either way, one assumes that the parents, if they knew, would disapprove. So it’s slightly disconcerting, early in the Japanese drama Shoplifters, to see Shota (Jyo Kairi), a boy of roughly 11 or 12, stealing items at the grocery store with the active assistance of his father, Osamu (Lily Franky). Dad serves as lookout, signaling when the shopkeeper’s attention is distracted and letting the kid do the dirty work, but the crime appears to be his own idea. What’s more, when they arrive home with the loot, Osamu’s wife, Nobuyo (Sakura Andô), treats this misadventure not just as normal but also routine, suggesting that virtually everything they eat and own is obtained illegally. Given its title and this opening sequence, one might naturally assume that Shoplifters concerns an oddball family of professional grifters.

Yes and no, turns out. Writer-director Kore-eda Hirokazu has spent much of the past two decades examining and questioning the bonds that tie families together, via such extreme scenarios as a mother who abandons her four children (Nobody Knows) and two couples who discover that their pre-teen boys were accidentally switched at the hospital as newborns (Like Father, Like Son). Shoplifters, likewise, soon reveals itself as a meditation on family—specifically, on the makeshift family, assembled by choice rather than by inherited genes. Happening upon a little girl (Miyu Sasaki) freezing in the winter cold, with no adult anywhere around, Osamu impulsively takes her home. After discovering signs of physical abuse, he and Nobuyo decline to contact the authorities, giving the girl a new name, Rin, and effectively adopting her. Technically, this qualifies as kidnapping, though it’s hard to feel outraged by the sight of a neglected child finally receiving love and care, even in such threadbare circumstances. Things are even more complicated than that, though, as a startling series of late-breaking revelations makes disturbingly clear.

Shoplifters earned Kore-eda the Palme D’Or, and while it wasn’t the best film to compete at Cannes this year (that would be Burning), it’s arguably his strongest to date. He’s always excelled at orchestrating chaotic ensembles, and this household—which also includes a pachinko-addicted grandma (Kore-eda regular Kirin Kiki, who passed away, sadly, a couple of months ago) and an adult daughter (Mayu Matsuoka) who performs in a peep-show booth—is so memorably ramshackle that it’s a wonder the crew managed to find room for the camera equipment among the jostling bodies and piles of pilfered debris. What these people have in common beyond a shared surname really pounds the film’s theme home with a sledgehammer, but there are numerous tender, affecting moments en route to the finale’s tearjerker overdrive, many of them productively tangential to the overarching idea of choosing one’s own family. A subplot involving the adult daughter and a desperately shy client pays unexpected dividends, and even a seemingly gratuitous sex scene (which refreshingly treats its middle-aged characters as if they were young hotties) boasts a disarming frankness that will affect how viewers assess what happens later. Is it wrong to steal a loaf of bread if you’d otherwise go hungry? That’s not the question that Shoplifters asks, ultimately, but the questions that it does ask inhabit the same murky ethical domain, and are just as difficult to answer.