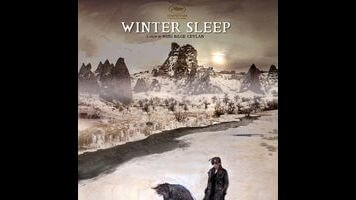

Both views were essentially accurate, it turned out, as Winter Sleep was justly lauded as a career culmination and overvalued by the easily awestruck. At bottom, it’s a stealth portrait of an asshole: Aydin (Haluk Bilginer), the middle-aged owner of a fantastically gorgeous hotel carved into the side of an Anatolian mountain. Proud of his status as the ruler of this petty fiefdom, Aydin spends his days schmoozing with guests, dealing with complaints from the tenants of shabby properties he owns near the foot of the mountain, and researching a book he intends to write on the history of Turkish theater. He still has time, however, to heap endless condescension upon his considerably younger wife, Nihal (Melisa Sözen), who galls him by attempting to carve out just a tiny portion of her life that he doesn’t completely control. Her efforts to fight back in whatever way she can eventually intersect with an early incident in which a small boy throws a rock at a passing truck (in which Aydin is a passenger), breaking a window.

If that synopsis doesn’t sound like it would demand more than three hours of screen time, well, such is the glory and the frustration of Winter Sleep. Ceylan’s synthesis of exterior (landscapes) and interior (mental states) is typically masterful in the film’s first and final hours, when the characters are frequently defined, or at least heavily informed, by their surroundings. And Bilginer gives a truly towering performance as Aydin—arguably the year’s best, across all categories. Rarely has a portrait of a monstrous personality been so richly detailed in its self-justification (and self-delusion); Bilginer makes it painfully clear at every moment that Aydin, even as he relentlessly steamrolls over people, believes himself to be a mensch, misunderstood and unappreciated by those around him. Ceylan doesn’t give Aydin any speeches to that effect—it’s all in his maddeningly arrogant manner, which he poorly masks with pseudo-empathy. Winter Sleep is well worth seeing for Bilginer’s work alone. That it’s also gorgeous is just gravy.

Unfortunately, Ceylan isn’t entirely averse to speechifying. His inspiration for the film was a couple of short stories by Anton Chekhov, and at roughly its midpoint, he takes the camera inside the hotel and has Aydin engage in two of the longest and most stultifying conversations ever filmed—scenes that might work beautifully in fiction, or onstage, but bring the movie to a tiresome standstill. One of them is between Aydin and his sister, Necla (Demet Akbag), and concerns the columns Aydin writes for a local newspaper, Voices Of The Steppe. The other is a knock-down, drag-out with Nihal about a charity function she’s planning, with which she does not want his help. Each runs, no kidding, somewhere in the neighborhood of 20 to 30 minutes, continuing long, long, long after its dramatic gist has been beaten into the ground. Had Ceylan resisted the temptation to bloviate in these two scenes, which together make up roughly a third of Winter Sleep’s three hours, the film would have been much stronger. Would it still have won the top prize at Cannes, though? We’ll never know, but it’s fair to wonder.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.