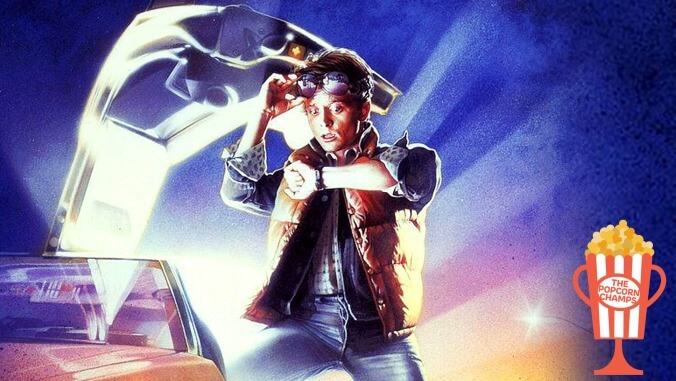

Though set in two bygone eras, Back To The Future is timeless blockbuster fun

Image: Graphic: Jimmy Hasse

“Sir, do we get to win this time?” That’s John Rambo, talking to his old mentor Colonel Trautman, at the beginning of Rambo: First Blood: Part II, the No. 2 movie at the 1985 box office. The answer, we’ll soon find out, is yes. John Rambo, a disturbed traumatized Vietnam veteran in prison for his destructive rampage across a small American town, is about to go back to Vietnam. There, he will rescue forgotten American POWs and effectively nullify the USA’s great world-stage humiliation. John Rambo is about to rewrite history.

The second- and third-highest grossing films of 1985 are both greased-up absurdist Sylvester Stallone action sequels. Both Rambo and Rocky IV are about restoring American primacy in a threatening and unpredictable world. In Rambo, Stallone goes to Vietnam and rights old wrongs. Six months later, in Rocky IV, Stallone goes to Russia, takes on an ice-blooded colossus, and convinces a Soviet crowd to cheer for American fighting spirit. Watching these two beautiful, ridiculous movies is like injecting yourself with a cocktail of cocaine and anabolic steroids. They’re both big, dumb, loud, awesome spectacles. But as huge as both of them were, they both lost the year to a smarter, smaller movie that, just like Rambo, was about rewriting history and correcting past mistakes.

Back To The Future almost didn’t get made because it wasn’t horny enough. Most of the major Hollywood film studios turned the movie down. Thanks to the out-of-nowhere 1981 smash Porky’s, studio executives believed that people would go see pictures about ’50s teenagers only if those movies were idiotic sex farces. Back To The Future was not an idiotic sex farce, and writer-director Robert Zemeckis and his cowriter, Bob Gale, didn’t have great track records. Steven Spielberg had been executive producer for their first two films, 1978’s I Wanna Hold Your Hand and 1980’s Used Cars. They’d both lost money. Zemeckis and Gale had also written 1941, Spielberg’s first failure. For years, then, the Back To The Future script went nowhere.

All that time around Spielberg eventually paid off, though. Zemeckis finally hit with 1984’s Romancing The Stone, which reimagined Raiders Of The Lost Ark as a quip-happy romantic comedy. People in Hollywood didn’t have high hopes for Romancing The Stone, and Zemeckis was actually fired as the director of Cocoon when studio heads saw an early screening of Stone. But Stone became one of the year’s biggest hits, and it gave Zemeckis the latitude to make Back To The Future, with Spielberg on board as executive producer. (Ron Howard ended up getting the Cocoon job. That movie turned out to be an even bigger Spielberg bite, and also a big hit.)

Spielberg’s fingerprints were all over the big movies of 1985, or at least the ones that didn’t feature an oiled-up Sylvester Stallone. Spielberg himself took on the questionable task of adapting Alice Walker’s novel The Color Purple. His film was clear awards-season bait, and it won nothing, despite 11 nominations. But The Color Purple was still one of the year’s highest earners, even though it’s a rough watch. Spielberg was also executive producer of The Goonies, and he’s got to, at the very least, be the reason that Robert Redford wears an Indiana Jones hat in the sweeping and old-timey Best Picture winner Out Of Africa. But with Back To The Future, Zemeckis essentially did Spielberg—the knowing suburban nostalgia, the eye-twinkling quips, the scenes of open-mouthed special-effects wonder, the booming score—better than Spielberg himself could’ve done at the time.

It wasn’t an easy process. Zemeckis, for instance, had to fend off a studio exec who was determined to change the film’s title to Space Men To Pluto. At first, Zemeckis couldn’t land the star he wanted; the producers of the hit sitcom Family Ties wouldn’t give the young Michael J. Fox enough time off to make the movie. Instead, Zemeckis went ahead with Eric Stoltz, a young actor who’d impressed him in Peter Bogdanovich’s Mask. But after burning through weeks of production and millions of dollars in budget, Zemeckis looked at his footage and realized that Stoltz simply wasn’t funny enough to carry the movie. So he went back to the Family Ties producers, and they worked out a deal where Fox could film the TV show during the day and film Back To The Future at night and on weekends. By the end of production, Fox was so drained that he couldn’t remember most of what he’d shot.

It’s hard to imagine anyone being more perfect for the Marty McFly role than Michael J. Fox. In Back To The Future, Fox is small and squinty and breezily charismatic. Fox was 24 when he shot the film, but he was so good at stammering disbelief that he easily passes as a high schooler. On top of that, Fox was already famous for playing Alex P. Keaton, a sort of avatar of Reagan youth. The central conceit of Family Ties was that the aging-hippie parents can’t understand how their son has become a square and uptight young Republican. In the ’80s, a big part of the Republican sales pitch was a return to ’50s values. Marty McFly and Alex P. Keaton are two very different characters, but there’s still something primally satisfying about seeing this kid go back to the ’50s and learn that ’50s values are not what he thought.

None of the actors in Back To The Future were movie stars at the time. Fox and Christopher Lloyd were both familiar from sitcoms. (Lloyd had been part of the ensemble on Taxi, which had finished its run a couple of years earlier.) Lea Thompson had only done a few films at the time; she got the part because she’d played opposite Eric Stoltz in The Wild Life a year earlier. Crispin Glover, who played Marty’s father George McFly, was actually three years younger than Fox, and he’d done bit-part duties on a couple of Family Ties episodes. One of the great things about Back To The Future is that it gives Glover a chance to be wonderfully, flamboyantly weird, performing symphonies of awkwardness just by walking into a diner or dancing rhythmlessly. A year later, Glover would play a braying psychopath in River’s Edge, and this would lead to a career primarily composed of bugshit performances.

If Back To The Future has a clear star, though, it’s the script. Zemeckis and Gale’s screenplay is a marvel of narrative tricks and giddy momentum. (The first sequel, a big hit in 1989, is even more dazzling on that score.) The premise is not exactly a guaranteed home run: An ’80s teenager accidentally travels back in time and threatens his own existence because his mom takes a romantic interest in him. But Zemeckis and Gale take that idea and build a charming and inventive sci-fi thriller out of it. Clocks are the first things that appear onscreen in Back To The Future, and we see them again and again throughout the film; Christopher Lloyd, like the silent-era slapstick star Harold Lloyd before him, even dangles from one during the climax. (Harold and Christopher aren’t related, but they’ve got to be part of the same physical-comic genealogy.) Marty McFly has to keep moving throughout; his very existence depends on it.

Back To The Future is jammed full of clever touches. Zemeckis makes Hill Valley feel like a real place, even though it only exists on a Hollywood backlot, and he sells the difference between the ’80s version of the place and the ’50s one. The Ronald Reagan jokes are low-hanging fruit, but they work beautifully. The film indulges in the same ’50s nostalgia as movies like Grease, but it also alludes to the idea that it wasn’t a great time for everyone—the diner owner, for instance, harrumphing about the very idea of a black mayor in a throwaway moment. And there are touches of foreshadowing throughout. VCRs and cable TV were both in their relative infancy in 1985; I wonder if Zemeckis had any idea just how many repeat viewings that Back To The Future would get. The picture earns its cliffhanger ending; it truly makes you want to see what’s going to happen to these people later on.

For an ’80s comedy, Back To The Future has aged remarkably well. One of the big plot moments revolves around an attempted rape, but Biff Tannen is the story’s villain; he’s supposed to be an irredeemable shitbag. The idea that Marty McFly invented rock ’n’ roll and that Chuck Berry ripped him off is the type of thing that sends music dorks like me on indignant “well, actually” rampages, but as jokes go, it’s pretty good. (That joke comes out of a truly fun musical sequence, though Fox’s lip-syncing bothers me more than any time-travel-related logical paradoxes.) The only part of the movie that seems risible today might be the broadly stereotyped Libyan terrorists, and even that gives us the honestly-pretty-funny image of militant jihadists speeding through suburbia in a broken-down VW bus.

Even though Back To The Future is a movie about two specific historic moments, it’s held up. When I showed my kids Back To The Future, I worried a bit that they wouldn’t get anything out of it. To the, 1985 is even more remote than 1955 was to me as a kid, so I figured that none of the fish-out-of-water jokes would land. And they didn’t, not really. But the cartoonish characters, the convoluted situations, and the narrative momentum sucked them in anyway.

Though it’s fast and complicated, Back To The Future really does come off as a contained human story. Marty McFly learns that his father was a pathetic and horny weasel at his age, but he also sees his own worst tendencies in his father. He’s forced to confront the idea of his mother as a horny human being. (The chemistry between Fox and Lea Thompson is still surprisingly intense, and it probably helped spawn at least one internet-porn subgenre.) Ultimately, the movie turns into a parable about the importance of assertiveness. When George McFly punches Biff, he’s like the caveman in 2001: A Space Odyssey who first figured out how to use a bone as a weapon. When Marty returns to a changed 1985, the world he sees is shaped by a father who, awkward though he may be, is willing to take some chances.

Thirty-five years later, Back To The Future is an even more satisfying rewatch, since it’s become its own kind of time capsule. There’s the sight of Billy Zane, for instance, as the least memorable of Biff’s goons. (Zane didn’t even get the 3D glasses. He just got the toothpick.) There’s Huey Lewis, adorably goofy in his quick cameo, complaining that Marty McFly’s version of his own song is “just too darn loud.” There are the great scenes of Michael J. Fox and his stuntmen skateboarding, which helped spread skate culture across America in a crucial moment.

And of course, there’s Biff Tannen, a glass-jawed fuming idiot bully who might be the single most evocative character in the film today. Biff looks, talks, and acts a whole lot like Donald Trump, the baffling-cultural-relic president of our own corroded age. Bob Gale has said that Biff was at least partially modeled on Trump — something that becomes a whole lot plainer in the sequel, when a rich Tannen is running a casino plastered in his own stupid name and image.

But Back To The Future doesn’t need those weird new touches of resonance, just like it doesn’t need all the nostalgic humor that’s purely theoretical for most anyone younger than 70 today anyway. Like at least a few other big movies of its day, Back To The Future is about rewriting history. But unlike those others, it’s good enough to transcend that history as well.

The contender: Peter Weir’s Witness, the No. 9 movie at the 1985 box office, presents its own vision of nostalgic escape: A Philadelphia detective finds meaning and community while hiding out among the Pennsylvania Amish. It’s a great white-knuckle crime thriller with a couple of classic action scenes. But it also finds time for moments of great lyrical beauty—places where you can feel Harrison Ford’s character losing himself, and where you can start to lose yourself, too.

Next time: With Top Gun, Tony Scott uses MTV-style montages and coked-out Bruckheimer/Simpson plotting to make what amounts to a naval recruitment film. But he also gives a weirdly compelling image of masculine vulnerability, and he transforms young star Tom Cruise into a global icon.

GET A.V.CLUB RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Pop culture obsessives writing for the pop culture obsessed.