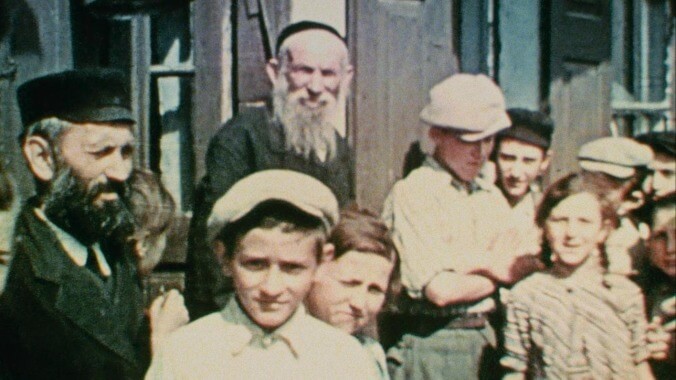

Townspeople of the predominantly Jewish village of Nasielsk, Poland, in 1938 as seen in Bianca Stigter’s Three Minutes: A Lengthening. Photo: Family Affair Films, © US Holocaust Memorial Museum

It takes only a few more moments than the duration in the title of Three Minutes: A Lengthening to realize what this documentary is going to be. Other voices will appear on the soundtrack, and the filmmakers will tell a story. But the visual element—the primary canvas for cinema as art—is going to focus only on these three minutes of footage for the entire film.

Not that it’s on a loop. The imagery runs backward and forward, gets freeze-framed, goes through different filters, and is blown up, reduced, diced, and re-assembled like playing cards. But director Bianca Stigter fully commits to this formalist dare—and it pays off tremendously.

The three minutes (actually, a little over) of footage, shot in 1938, was something nearly lost to the ashes of history. Glenn Kurtz, a New York-based music writer, discovered it among his grandfather’s things. Had he waited one more month, it would have deteriorated past the point of restoration.

Kurtz’s grandfather, David Kurtz, was a Polish-born Jewish-American immigrant who toured Europe after experiencing business success in the New World. He visited the typical spots—London, Paris, Rome—but in-between he snuck a visit to Nasielsk, a small town best known for its button factory.

Nasielsk was over 40 percent Jewish, and Kurtz visited that section in August 1938, keen to shoot some of the buildings that he remembered from his youth with a new movie camera. The villagers, quite unused to outsiders holding film cameras, got in his way.

A few months after his visit, the town’s Jewish community was rounded up on trains, sent to ghettos, and, eventually, extermination camps. Very few survived. Indeed, these three minutes are the last images—the only ones—of an intact, thriving community, just before the nightmare of Nazism descended upon them.

When Glenn uncovered his grandfather’s footage, he worked tirelessly with agencies (like the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.) to contact a survivor, and was eventually able to piece together some of the faces seen in the short reel. His efforts resulted in a book, Three Minutes In Poland: Discovering A Lost World In A 1938 Family Film. Stigter’s film becomes an adaptation of sorts—examining the examination, walking us through Glenn’s discoveries, and presenting new interviews with those connected to the images onscreen. Helena Bonham Carter reads a voice-over, written by Stigter, that veers between straightforward narration, art theory, and poetic philosophy.

Zeroing in on just one stretch or frame of film footage for clues has been a pastime for many going back to the work of Abraham Zapruder. (Don DeLillo’s “Texas Highway Killer” section from Underworld is a fine example of how nothing can ever be considered “watched out.”) Stigter sinks her teeth into the “sleuthing out” aspect (how an almost unreadable storefront sign gets translated is particularly thrilling) but balances that exercise with a healthy serving of metaphysical contemplation. What does it mean to search? What does it mean to forget? What does it mean to remember?

Most striking, of course, are stories of the few that survived—both who and how. But these are common in Holocaust documentaries. Stigter also ponders more mundane topics: the social implications of what kind of hat you wore in the Jewish section of 1930s Nasielsk can tell a whole story in an instant. But only if you have the right person interpreting the image.

This is Amsterdam-born Stigter’s first feature (a short one at 70 minutes) after working in shorts and producing films by her husband, Steve McQueen. (The Oscar-winner is a producer on this film.) In press notes, she says she came upon the story of the surviving three minutes while poking around on Facebook. That kind of chance connection speaks to an essential part of how we’re able to access this window into the past at all; naturally, it makes one melancholy to think about how easily, and swiftly, whole cultures have evaporated or been erased. Newer technology can conserve images, but can they retain understanding? What good are clouds and clouds of data with no one to explain their meaning?

Three Minutes is an atypical documentary, for its repetitive use of the images alone. There is, at the very end, a rather striking and deliberate flash: a 1/24th-of-a-second tag, in which Kurtz clearly moved on from Poland to somewhere a little more glamorous. (It’s a shot, from a boat, of Switzerland.) In a strange way, this fraction of a shot offers a powerful conclusion to the film. The original author of the work had no idea that he’d captured something so meaningful—for him, it was just part of the trip. But in the context of the three minutes, it can be interpreted as escape or hope, or maybe as turning away. Perhaps Stigter’s next act won’t be ruminating on a stashed and forgotten reel, but just a single image.