Three novels you can read in a day

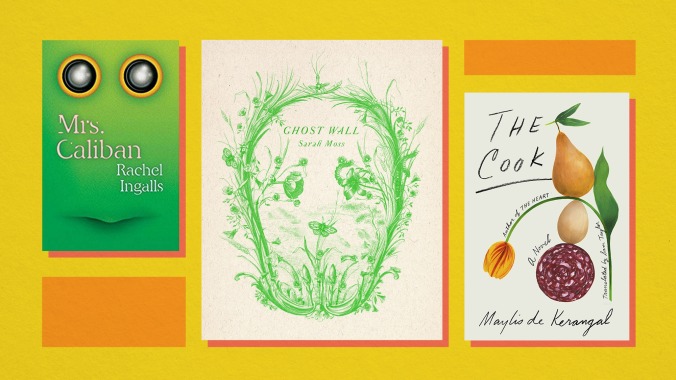

Mrs. Caliban by Rachel Ingalls (New Directions, 128 pages)

First published in 1982 and re-released in late 2017, Rachel Ingalls’ Mrs. Caliban concerns a lonely woman named Dorothy and her brief affair with a kind, gentle frogman, escaped from a local laboratory. Ingalls relates both joy and pain quickly, her prose swift and unsentimental, even when detailing the tragic. Mrs. Caliban shares a number of plot elements and themes with Ingalls’ 1983 novel, Binstead’s Safari, which will be reprinted, also by New Directions, later this month. Both stories involve an unhappy housewife, a cheating husband, noted childlessness. In both, the husband’s unfaithfulness is answered by an affair of the wife’s own. Millie’s romance is related to, but does not form the bulk of, her newfound happiness in Binstead (there’s also a haircut), which is longer and looser than Caliban. Most notable in the latter are the tender conversations between Dorothy and frogman Larry when they explain to each other the differences between their worlds. “‘It’s always there, like your heartbeats,’” Larry says about the sound of the ocean. “‘The sea speaks to us. And it’s our home that speaks.’” There’s a patient curiosity on both their parts, those passages almost reading as instructions on how to care for and about another person. Or frogperson, as the case may be.

Ghost Wall by Sarah Moss (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 144 pages)

There’s a similar care between the 17-year-old narrator and her new friend and crush in Sarah Moss’ Ghost Wall, released last month. Sylvie, along with her mother, has been brought by her bully of a father to the north of England to act as an ancient Briton as part of an immersive education project with a group of high school students. Even in the reenactment, the gender disparities of today are well-intact: “Your dad and Jim… they’re not much interested in the foraging and cooking, they just want to kill things and talk about fighting,” Molly says to Sylvie. There’s a cultural divide between the two of them—Sylvie’s family has less money, comes from the south—but they form a slow but certain bond. The headstrong Molly often says what Sylvie, out of fear of her father, cannot; and Sylvie impresses Molly with her quiet wit and knowledge of nature, rendered here in vivid, lyrical prose: Grassy slopes “vibrat[e] with bees”; fish are killed then “opened out like pages.” And: Molly’s hair is “like the grain in polished pine.” It’s heartbreaking to discover how Sylvie became so adept at describing the world around her—such focus can be a survival tactic—but it shows just how seamlessly the novel’s poetic writing is interwoven with its thematic significance.

The Cook by Maylis de Kerangal (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 112 pages)

It’s a decidedly lighter appeal to the senses that French writer Maylis de Kerangal makes in The Cook, the perfect thing for those who get aroused reading bistro menus. There are some rather nice lists of risottos and sorbets. Like Moss, de Kerangal conjures the physicality of her subject through evocative language: here, instead of nature, cooking. There is the “moist breath of the whisk in the cream” or “the pointillist line of balsamic vinegar on porcelain and the petals of beetroot chips forming a rose.” It’s sexy stuff, a closeup of a pristine cake being covered in a glossy ganache. But it’s not all wine and beet roses. In its portrait of a principled young man mastering his craft, The Cook does not ignore the grueling, often violent world of professional kitchens. De Kerangal captures both the elegance and the grind: “A worker’s hand and an artist’s hand,” as the narrator says. It’s not a drawback that the book’s objectives are modest, its pace leisurely. Just as one waits for July to eat fresh tomatoes, this “edible capsule” is perhaps best read not when it comes out next month, but in the dog days of summer—while lazing in a hammock or eating on the patio of some European café not yet inundated with tourists.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.