Three-part Netflix doc jeen-yuhs offers an incomplete telling of the Kanye West story

There are some big gaps in this Hoop Dreams-style portrait of the rapper's life and career

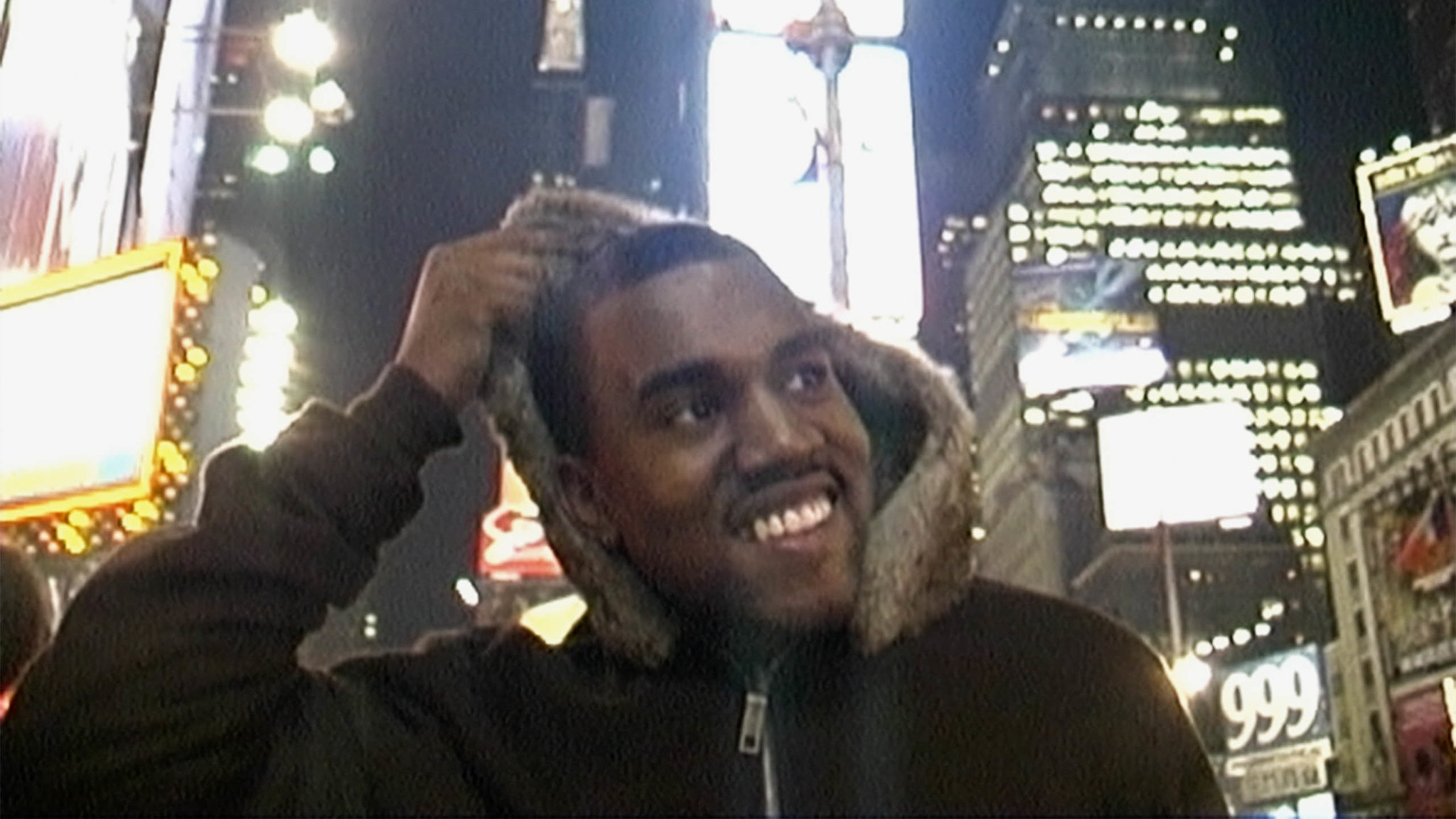

Image: Photo: Netflix

There’s a revealing moment early into jeen-yuhs: A Kanye Trilogy where a young Kanye West explains why he’s so cocky, years before he has much to be cocky about. “Hip hop is always about fronting,” shrugs the budding Chicago superstar, then barely old enough to drink, as a big smile creeps across his baby face. Humility, it would seem, has never been one of West’s defining traits. Then again, as he explains, bravado is part of the image—a performance required of anyone looking to make it in the rap game. What was exciting about Kanye, when he first blew up in the early 2000s, was how he cooked that acknowledgement into the music, mixing his doubts with his braggadocio, suggesting they were intimately related. That wasn’t subtext. It was right there in “All Falls Down,” where West established himself as a new kind of hip-hop star, vulnerable and relatable and honest enough to admit his insecurities.

That’s the “old Kanye,” identified as so by the artist himself a few years ago, with a self-conscious wink of a half-song. We get a lot of the old Kanye, a.k.a. the very young Kanye, in jeen-yuhs. Technically, this trifurcated documentary, which premiered in part at Sundance this evening and drops in full on Netflix next month, spans the entire length of West’s career, from his early days as a fledgling hip-hop producer with dreams of grabbing the mic to his current life as a gospel-choir leader in a Make America Great Again hat, incensing fans by the tweet. But the project is undeniably lopsided in its focus, spending two of its three installments—equal in length at about 90 minutes apiece—on the rise-to-fame portion of the Kanye story. As it’ll become clear later, that’s partially a matter of what footage was available and when it was shot.

“Work in progress” read the version of jeen-yuhs critics were provided. Perhaps at this point, anything related to Kanye West should come with such a disclaimer. (What, you thought Donda was done, just because you’ve been listening to it for a week?) jeen-yuhs has been a work in progress for a long time. Production on it began in the late 1990s, when Clarence “Coodie” Simmons—one half of the directing team now known as Coodie & Chike—met a 21-year-old West, who agreed to let the filmmaker follow him around with a camera while he hustled to get the attention of his musical heroes. Coodie, who would eventually co-direct with Chike Ozah the acclaimed video for Kanye’s breakout first single “Through The Wire,” just kept rolling. (He was inspired by Hoop Dreams, another documentary filmed over several years and built around the big aspirations of young, Black Chicagoans.)

The first installment, vision, is the most interesting and entertaining, mostly by virtue of catching West at an embryonic stage of unguarded ambition—a hungry go-getter, spitting bars for anyone who will listen. In one early episode, Kanye and his crew roll up uninvited to Roc-A-Fella, ready to lobby Jay-Z—whose hit “Izzo (H.O.V.A.)“ Ye had just produced—for a proper record deal. West walks from room to room, rapping along to “All Falls Down,” while one marketing rep looks on completely unimpressed. It’s a rare moment of indifference captured by Coodie’s camera; most of the footage here amounts to a series of miniature star-is-born moments, interspersed with appearances by West’s late mother, Donda, who the film establishes as a beacon of support.

The director neatly identifies most of the conflicts of Kanye’s creative infancy: how his unthreatening image as a so-called “backpack rapper” made him an outlier in the genre circa the turn of the millennium, and maybe a tough sell to record execs; how Roc-A-Fella, unlikely corporate villain of the story, kept trying to pigeonhole him as a beats man instead of an MC; how the near-fatal car accident that left his jaw broken in several places slowed the momentum of his career, delaying the release of his debut album, The College Dropout. The recording of that instant classic—still Kanye’s biggest seller, thanks in no small part to unconventional, devotional FM smash “Jesus Walks”—makes up the majority of the second episode, purpose. We get a lot of scenes here of big-name rappers picking their jaws up off the floor, though the most telling, pointed inclusion might be Pharrell encouraging Kanye to “keep his perspective” and essentially not let fame go to his head.

In the space between mundane hangouts and game-changing studio sessions, Coodie wedges in elements of his own story as an artist who, for years, tied himself to the upward trajectory of someone else’s calling. He narrates the film in a sleepy-relaxed voice over, repeatedly reiterating points he’s already made and underscoring the more uplifting aspects of Kanye’s rags-to-riches saga. (Generically dreamy ambient music does a lot of the lifting there, too; all of the actual Kanye music heard in the film is diegetic, blaring from a speaker, possibly to get around rights clearance issues.)

Increasingly, the impression of certain festering resentments begins to creep into the narration. “I guess things change when you get famous, because Kanye doesn’t want the world to see him yet,” Coodie remarks when West objects to a much earlier release of the documentary. Later, he complains that “No one would return my calls” when he tried to reach out to a then-recently hospitalized West. An animating tension keeps bursting through the inspirational framework: an old friend and collaborator disappointed to see this international superstar cut him out of his circle.

Coodie isn’t coy about the access he lost when Ye went supernova. But it leaves jeen-yuhs with no behind-the-scenes footage of West at peak popularity and cultural significance; those years of chart-toppers and heavily publicized controversies (“I’ma let you finish,” “George Bush doesn’t care about Black people,” etc.) are covered in speedy montage made up entirely of publicly available clips. It was only a few years ago that Coodie worked his way back into Kanye’s orbit. The film’s final installment, awakening, offers an uneasy, very incomplete portrait of the star’s rocky experiences leading up to the pandemic, plagued by public speculation about his mental state. “It just didn’t feel right to keep filming,” Coodie confesses after catching one rant on camera… but he still includes the footage in the movie, and picks up with a no more centered-seeming Kanye a few weeks later, having apparently decided it was now fine to film him during this difficult period. There’s not much of a coherent perspective to this passage of the movie, courtesy Kanye or Coodie.

A couple days ago, West took to Instagram to demand final cut on the movie—creative control he’s not likely to get from Netflix, who aren’t in the business of missing release dates. jeen-yuhs can’t exactly be called an authorized account; there are some unflattering moments he would likely excise. But mostly, the project reinforces the image Kanye has long projected of a complicated, outspoken artist who believed in himself when few did and achieved his wildest dreams. The best objection to the films is that they’re fundamentally a “work in progress,” as a portrait of an artist who’s turned his whole life into a serialized melodrama of public conflicts and screeds, subject to change by the hour or the post or the latest threat to kick Pete Davidson’s ass. Any documentary about his life will become outdated sometime between pressing play and watching the credits roll. This one has big holes long before that.