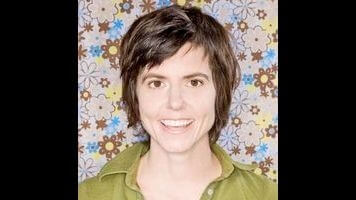

Tig Notaro shows another side of her grief in I’m Just A Person

There are many schools of thought on what, if anything, happens after death, but one thing mourners can count on are platitudes. “They’re in a better place now.” “They were called home.” This isn’t a condemnation of the sentiment behind such responses, because it’s hard to know exactly what to say in those situations, but these words rarely offer much consolation. In 2012, comedian Tig Notaro endured a year of unbearable loss: She had to take her comatose mother off life support as she herself was near death thanks to a particularly vicious bacterial infection, only to be diagnosed with stage 2 breast cancer a few months later.

In that time, Notaro must have heard hundreds of bromides about maintaining a positive outlook, or otherwise reassuring her that she wasn’t being “given” any more than she could handle. The only such note she appears to have taken to heart is that death can be transformative or, at the very least, cathartic. Her candor about her cancer diagnosis led to one of the most inspired comedy albums of recent years (2012’s Live), and Notaro also channeled her grief into the poignant and powerful pilot One Mississippi for Amazon. And this month, Notaro is publishing I’m Just A Person, a memoir about what she endured in that clusterfuck of a year.

At about 240 pages, I’m Just A Person is a sprint down memory lane for Notaro, opening with her description of the cab ride she took from the hospital—and her dead mother’s bedside—to her childhood home. Her inability to remember the address angers the cab driver, but she assures him she can find her way home, something she’s already demonstrated by flying from Los Angeles to Texas despite being in considerable physical and emotional pain.

Was I even in the right life anymore? My mother died two hours ago. I’ve lost so much weight, my pants are falling off.

Despite eventually arriving at her destination, Notaro never seems to make it back home, because there is no such place without her mother. Her stepfather, Ric, is an especially poor communicator, and while he doesn’t shut her out, he seems more intent on ensuring his surroundings—namely, the house he shared with Notaro’s mother, Susie—meet his own exacting standards. He also suggests that Susie’s death has severed his ties to Notaro and her brother Renaud—they’re now as related as “strangers on the street.”

Ric’s actions aren’t born of malice; he’s also just trying to cope with the loss. But they provide a surprisingly welcome distraction to Notaro, who avoids looking at pictures of her mother in happier, healthier days while also obsessing over the sound Susie’s head must have made when it struck the tile floor. There’s no real respite for the comedian, though, as she must pick out Susie’s outfit for eternity, console the grief-stricken people on the periphery (like a dermatologist), and reconcile others’ romanticized vision of her mother with her own lived experiences.

These would be superhuman feats for anyone, but they’re made alternately easier and more difficult by Notaro’s bacterial infection, a romantic break-up, and finally, a cancer diagnosis. The author can’t rely on her intestinal pain and other medical concerns to relieve her of her sorrow for long; she admits that while she could learn to eat differently, there’s just no replacement for her mother.

I’m Just A Person touches on a lot of the same tragic material that Notaro first shared in Live, the documentary Tig, and her HBO special Boyish Girl Interrupted, in which she first made the distinction that she’s just a person and not a hero for having survived cancer. And yet, this written record of her grief isn’t just a retread. It’s supplemental, yes, but also transcendental—here, Notaro isn’t as concerned with pacing or giving the audience a break from her misery. As a stand-up comic, Notaro is guileless, and here she’s even less concerned with the performance elements of the story.

That’s not to say the book isn’t funny—there’s still plenty of levity, but it frequently gives way to important revelations, like Notaro’s realization that, contrary to popular belief, she had been given more than she could handle. Her grief and recovery are in their rawest forms in I’m Just A Person, but so is her hope. Notaro closes the book with a quote from her mother that could easily appear on a fridge magnet, but has always comforted her nonetheless: “Life is all about change, and if you can’t keep up with it, it’s going to leave you behind.”