As the awards season reaches fever pitch, drawing out discussions of the best movies of 2013, a critical conflict has emerged between David O. Russell’s American Hustle and Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf Of Wall Street. At first glance, these two films make perfect opponents, especially in discussions focusing on the likability and culpability of their characters, or whether the Scorsese style is better employed by Russell or by the master himself. But while the movies share some superficial common ground, they’re less aesthetic rivals than complementary entries in 2013’s yearlong cinematic consideration of wealth and success in America. The films should not be considered an either-or proposition, but a vital and distinct piece of a larger picture.

Russell has been accused, in tones variously admiring and disdainful, of “doing” Scorsese in his con-artist picture American Hustle. And yes, the movie does bring Scorsese to mind with its multiple narrators, feverish use of pop music, and worthwhile role for Robert De Niro. But beyond those superficial similarities, Russell is working in his own recognizable style, that of The Fighter, Silver Linings Playbook, and even earlier features like Flirting With Disaster: Yammering outsider characters careen off each other as the camera careens around them. Russell’s work has also prompted (sometimes unflattering) comparisons to screwball comedy, but Russell’s characters are antsier than their screwball counterparts; they’re more insinuating and anxious. The playful gamesmanship of screwball gives way to desperation. No wonder the movie’s straightest straight man—played, naturally, by actual comedian Louis C.K.—keeps getting pushed to the margins of the story.

The characters’ aspirations also inform Russell’s use of music. Scorsese often scores sequences with pop-song cues, but Russell’s characters seem almost aware of the soundtrack, self-consciously attempting to match the glamour of a slow-motion walking shot. When Jennifer Lawrence actually breaks into a “Live And Let Die” sing-along it doesn’t feel much weirder or wilder than the rest of the movie. Glenn Kenny noted on his blog that Russell seems to wish karaoke had caught on in the ’70s, and that these song breaks contribute to the film’s undisciplined sprawl. The karaoke comparison is spot-on, but Kenny neglects to add that Hustle’s characters have clear motivation for performing a sort of spiritual karaoke. They’re imitating the flashy, outsized life they’re fantasizing about.

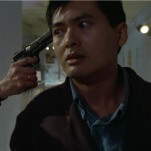

The real Scorsese, meanwhile, populates The Wolf Of Wall Street with less lovable strivers. Wolf doesn’t exactly open with Leonardo DiCaprio’s Jordan Belfort losing his humanity—it opens after it has long been lost, then jumps back to somewhat more innocent times—but for a three-hour movie, this loss happens with alarming speed. Early in the film, a green Belfort has lunch with a higher-up broker (one-scene wonder Matthew McConaughey), who disabuses his young protégé of the notion that his ultimate goal should be to make money for himself and his clients. Belfort takes to this guidance easily and eagerly. The rest of the movie follows his pursuit of more: more money, more drugs, more women, more property, and, as the FBI starts to close in, more time at the top before he gets dragged away. In a way, Belfort has a simpler (and baser) set of desires than those of American Hustle’s wannabe upper-middle-classers; the life Irving and Sydney are after in that movie wouldn’t rate at all on the Wolf scale of opulence. DiCaprio gets a mansion on Long Island where he can fly helicopters and stow his wife and barely seen kid, because that’s what wealthy people get. They get it all, and they get it on Long Island.

Wolf was actually DiCaprio’s second visit to Long Island’s Gold Coast in 2013; he also took up residence there for Baz Luhrmann’s adaptation of The Great Gatsby, which kicked off the year of wealth aspiration on film. Jay Gatsby is both more romantic and more tragic than Jordan Belfort. His ambition and success—albeit as a semi-gangster—serve, in his mind, to reunite him with Daisy Buchanan to recapture their relationship’s promise through lavish parties and the appearance of great success. The movie itself goes big and opulent, and Luhrmann was accused of misunderstanding or distorting Fitzgerald’s text by indulging in visual excess. But his approach is exactly right, and not so different from Scorsese’s in Wolf. Gatsby’s first party scene climaxes with a strong candidate for image of the year, or at least for DiCaprio’s lifetime achievement highlight reel: a dashing Jay Gatsby, facing the camera, glass raised, fireworks exploding in the background, “Rhapsody In Blue” on the soundtrack. It’s a glorious bit of seduction—aimed at Nick Carraway and the audience, incidentally, rather than Daisy—that the film needs in order to later articulate Gatsby’s core of sadness. Wolf Of Wall Street, set about 50 years later, powers past any sadness at the core of Jordan Belfort. It charges harder, no green light in the distance.

What Scorsese brings to this less emotional story is his own obsession, heedless of any worry over glorification. For him, fascination and guilt are knotted together; he’s very familiar with the intoxication brought on by morally repellant characters. Wolf, like Hustle, is almost a comedy, and uses its comedic sensibility along with that recognizable Scorsese momentum to push through the potential monotony of spending so much time with such unrepentant assholes. The freewheeling comic style, built around scenes that sound more like Jonah Hill improv than anyone might have expected from a Scorsese film, also helps the movie power through its lack of financial analysis. The milieus of both Hustle and Wolf—con artists and criminal—often inspire movies rich in procedural detail, but both these films resist explanations. While the cons shown in American Hustle are alternately simple (Irving makes people beg him for loan money, takes a fee, and never delivers) and vague (how does he continue to attract business over the long term?), The Wolf Of Wall Street subverts the expectations of faithful Goodfellas and Casino viewers that Belfort’s narration will offer a close look at the inner workings of Wall Street. Belfort offers some cursory explanation, but twice interrupts himself to tell the audience, in essence, “Look, the point is, we made a ton of money and it was mostly illegal.” Avoiding the criminal process in both of these movies works, because for the characters, criminal activities function the same way normal jobs do in other movies (or, you know, real life): They’re workaday means to an end.

The illicit activities of Hustle, Wolf, and Gatsby unfold between 15 and 90 years ago; the striver film of 2013 that actually takes place in contemporary times is Sofia Coppola’s The Bling Ring, a fact-based portrait of privileged Hollywood teenagers who took to burglarizing the homes of famous people mostly for the fun of it. These excessive partiers don’t have anything on Jordan Belfort; there’s no onscreen sex, the drugs are a lot less hard, and the stolen goods aren’t parlayed into life-changing riches. (Plus, none of the kids appear to really need the cash.) Like Gatsby, with its glorious introduction of the hero, and Hustle, with its group walks, Bling Ring features a gorgeous thesis of a shot: an epically slow push-in on the exterior of Audrina Patridge’s mansion as the kids run wild inside, elated to be celebrity-adjacent and hunting for souvenirs. Their actions are unmistakably childish, masked with an adult sense of narcissistic detachment, which makes the film play like a years-later echo of its 2013 cousins—particularly Wolf, whose characters are the right age to have fathered these little monsters.

Even The Bling Ring, though, doesn’t specifically address our current economy as it affects most people, and the periods of Wolf, Hustle, and Gatsby are even further removed. Wolf has been called a metaphor for the economic collapse of 2008, which seems like a sketchy connection when considering that Jordan Belfort’s key actions were always illegal, whereas much of the irresponsibility that resulted in the recent crash were technically (and frustratingly) lawful. But despite notable differences in the financial details, all four films reflect (rather than symbolize) the contemporary suspicion that we haven’t yet reached the good life that should be coming to us. Just as corporations expect endless growth of profits, these characters, placed on a continuum, form expectations of endless class mobility. If we’re scraping by, we should climb higher. If we’re well off, we should inch closer to celebrities. If we’re spectacularly well off, we should test the limits of human wealth and decency.

That continuum eliminates the perceived need to declare a winner between Hustle and Wolf simply because their release dates happened to coincide. If anything, their proximity to each other improves the whole lot of 2013 striver movies, relieving the pressure for any single film to provide a definitive statement. If American Hustle seems too enamored of its characters to provide a clear moral center, and if Wolf Of Wall Street refuses to clearly and unreservedly condemn Belfort as a sociopath, maybe it’s because both films—along with Gatsby and Bling—recognize the funny and sad inevitability of these money-based longings. There, in the end, is their commonality: not the disparate styles, but putting human faces on economic desires. Unconsciously put in dialogue with each other, Scorsese, Russell, Luhrmann, and Coppola make sure there’s no escaping it.