To sell out or not to sell out? A new book traces the punk boom of the ’90s and ’00s

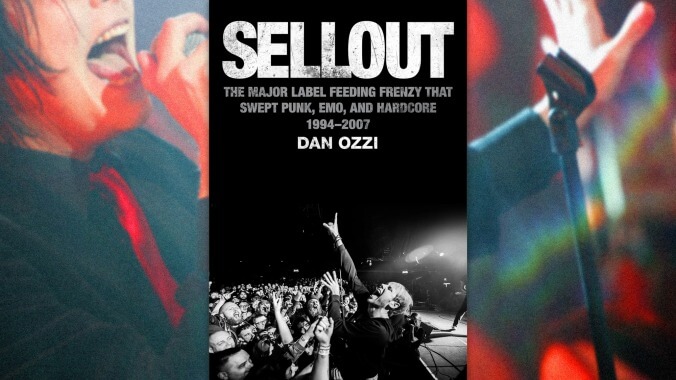

Dan Ozzi's Sellout follows more than a decade of punk, emo, and hardcore bands that endured the last gasps of backlash against major-label signings

It might be difficult to explain to young people who this summer witnessed the universal praise received by The Linda Lindas—the adolescent punk band that went from playing a public library to Jimmy Kimmel Live! in the course of a month—that mainstream fame hasn’t always been a respectable career move. As music writer Dan Ozzi explains in his engaging new book, Sellout: The Major-Label Feeding Frenzy That Swept Punk, Emo, and Hardcore (1994–2007), “For more than a decade, punk’s second brush with mainstream interest bitterly divided the scene.” For some, turning your back on a band that embraced crossover success was actually a badge of honor.

Compromising artistic or ethical ideals in the name of profit is an issue far from limited to the alternative music scene of the ’90s and ’00s. But it sometimes feels—for those who lived through it—like the response to artists selling out was never as vindictive, before or since. When bands gambled on the chance for wider recognition by signing with major labels like Geffen and Warner Bros., it was almost assured that part of their fanbase would not only rebuke the move, but actively campaign against the musicians they used to love. For artists who just wanted to get their songs heard by the largest possible audience, it was hard not to take the metaphorical (and sometimes literal) beatings personally.

Ozzi’s book gathers some of the most noteworthy bands to have gone through that experience in order to assess all the ways it sucked—and, in some cases, the ways it didn’t. Beginning in 1994 with Green Day and ending in 2007 with Against Me!, Sellout tracks 11 bands from their humble inceptions to major-label debuts in order to get a deeper understanding of what it meant to make the leap from independent existences in alternative scenes to trying to become financially successful acts.

What might be most surprising for those who saw the punk ethos reflected in these group’s early efforts is that, regardless of the scene that birthed you, major-label travails don’t always look that different, whether you’re the DIY-birthed punks of The Distillers or the classic-rock party animals of The Black Crowes. The relentless touring, drugs and alcohol, and glamorization of the hedonistic rock-star lifestyle happened for most acts, even if they began a career with nothing but two chords and a desire to stick it to The Man.

But who was “The Man,” actually? And what was the value in flipping him off in the name of some vague anti-consumer stance that didn’t necessarily reflect an artist’s true feelings? These are the knottier issues Ozzi delves into in Sellout. And while it can be fun to hear stories of out-of-control parties and behind-the-scenes bad behavior, the book’s real value comes through far clearer when the writer and his subjects grapple with the strange admixture of success in a punk subculture that often thrived in opposition to such a notion, and the personal and political ethos that were maligned by those who saw the very idea of joining “the music industry” as a betrayal. Or, as Jawbreaker’s Blake Schwarzenbach sang on “Boxcar,” “You’re not punk, and I’m telling everyone.”

In some ways, it’s a little surprising Ozzi didn’t simply opt for an oral history, letting only the artists’ voices shape the narrative. His style is briskly efficient and workmanlike, more often than not filling in the details and tracking the step-by-step history of what was happening, rather than offering his own opinions on the events. (He does, amusingly, exhaust the metaphors readily available for “tearing up the Billboard charts.”) Whether describing how Capitol Records wined and dined Jimmy Eat World in the lead-up to the act signing to the company and releasing Static Prevails, or calling attention to the tidal wave of sexism that so often greeted The Donnas during the promotional blitz for 2002’s Spend The Night, in a book that could’ve easily found plenty of room for snarky digs or respectful praise, Ozzi wisely keeps himself out of it.

He does, however, know who his stars are, and he makes no secret of granting more time and attention to them. There’s a reason he traces Green Day well beyond the initial release of Dookie!, or lingers on Blink-182’s runaway success for pages longer than the “sellout” arc. It’s mainly to ladle in a few more fun anecdotes, not spend more time with his central thesis. In tracing those more famous acts’ enduring popularity, he sometimes lets his focus obscure a bigger picture. (It’s a bit inaccurate to say that Blink-182 was “the first band that truly paid off” the promise of Green Day’s initial success and led mainstream punk into the 21st century, not when The Offspring is right there selling five million copies of 1998’s Americana.)

But it does lend a rawer and more moving sense of melancholy to the almost-was stories of bands like Thursday, which could never quite translate its fierce fandom into commercial success. And the intense personal journeys of game-changing artists like Against Me!’s Laura Jane Grace or My Chemical Romance’s Gerard Way help to leaven the burn-too-bright antics of At The Drive-In. It may be a bit inside-baseball at times for people who don’t follow these various scenes and their histories (describing a band as made up of “ex-members of Braid” when that band has never been mentioned in the book doesn’t illuminate the reference much), but overall, it’s a compelling and sometimes hair-raising account of what it meant to throw in your future with a large corporation in hopes of translating that effort into units sold—and the promise of a career in rock.

Author photo: Anthony Dixon