To thrilling effect, I Knew Her Well never lets us inside its heroine’s head

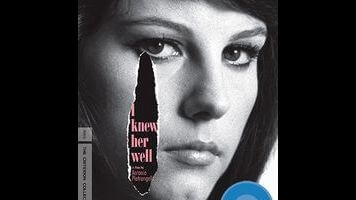

There’s no indication whatsoever of who the “I” might be in I Knew Her Well, Antonio Pietrangeli’s 1965 film about an aspiring actress-model named Adriana Astarelli (Stefania Sandrelli). Indeed, one of the many beguiling aspects of this underappreciated Italian tragicomedy, which joined the Criterion collection on Tuesday, is that nobody seems to know Adriana very well—including, arguably, the viewer, even after nearly two hours. That would be a problem in a conventional character study, but Pietrangeli’s film is anything but, to the point where placing it in an established genre or tradition becomes tricky. It’s traditionally been filed under commedia all’italiana (“comedy Italian style”), alongside such classics as Big Deal On Madonna Street and Divorce Italian Style. While there’s often a melancholy undercurrent to those films, however, few push it as far, in such a confoundingly subtle way, as I Knew Her Well, which keeps deflecting any indication of its protagonist’s unhappiness en route to a startlingly bleak conclusion.

Pietrangeli, who began his career as a critic, has so little interest in providing signposts or footholds that the film’s narrative is barely discernible for a long time. First seen sunbathing on the beach, Adriana has no clear goal or agenda, and the camera drifts alongside her as she goes about her daily life: working (at a beauty salon and a movie theater), dating (various no-good men whose abuse she blithely shrugs off), and often doing not much of anything. Gradually, it becomes clear that she has hopes of becoming famous, and has recently moved to Rome from the Tuscan village where she grew up in order to break into showbiz; she pays a writer to concoct a largely fictional biographical story about her in a movie magazine, and spends a lot of time hanging around parties waiting to be discovered. At the same time, though, she’s not willing to debase herself—a movie star (Enrico Maria Salerno) who wants to take her home gets rebuffed when he sends an emissary instead of approaching her personally—and is even willing to blow off a potential contact in order to babysit a neighbor’s infant. What’s going on in her head remains a mystery.

Sandrelli was all of 19 years old in 1965, and has a slightly unformed quality here that makes Adriana a poignant figure even when her intentions and motives are hard to pin down. Her performance fits beautifully within Pietrangeli’s offbeat structure, which deliberately downplays moments of significance. No scene seems explicitly designed to convey information; anything we learn about Adriana emerges almost incidentally. What’s more, while she’s in every single scene in the movie, scenes often begin without her, and continue for some time before her presence somewhere on the periphery is revealed. She’s barely around for I Knew Her Well’s most celebrated set piece, in which an aging actor (Ugo Tognazzi) nearly kills himself performing an impromptu tap dance routine at a party in an attempt to impress a director. But that actor’s desperation and willingness to humiliate himself nonetheless reflects Adriana’s own largely silent struggle, which reaches its depressing nadir when a newsreel interview is used to mock her.

Perhaps the most heartbreaking aspect of this remarkable character is her eternal optimism. One early scene sees her dressed to the nines, in full hair and makeup, for a commercial shoot in which only her feet will be visible on-camera; it’s clear that Adriana knows that, but couldn’t resist going all-out anyway. Later, a police detective who’s interrogating her (about a robbery committed by a guy she’d slept with, played by French actor Jean-Claude Brialy) tells her that he wishes he were her father, and she smiles warmly at him before clocking his expression and realizing he didn’t mean that in a positive way. And yet, while I Knew Her Well is ultimately revealed as the story of a naïve young woman getting beaten up by life in the big city, it’s not even remotely a dirge. Its sad ending is as short, sharp, and unexpected as are the various micro-flashbacks to Adriana’s past that recur throughout the movie, all of which serve a function that’s far more expressionistic than expository. If anything, the final shot feels like a slight betrayal, even though one can retroactively see that seeds for it had been planted along the way. Pietrangeli shot the film in gorgeous monochrome, but it’s the way that he resists making anything else black and white—at least until the last few seconds—that makes it such a quiet stunner.