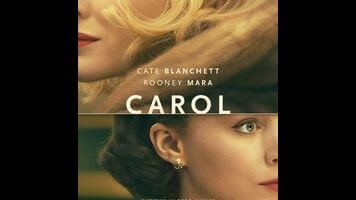

Todd Haynes goes back to the ’50s with a rapturous new romance, Carol

The most telling, period-defining moment in Carol, Todd Haynes’ superb adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s 1952 novel The Price Of Salt (originally published under the pseudonym Claire Morgan), gets no particular emphasis and could easily be missed. It occurs not long after young aspiring photographer Therese Belivet (Rooney Mara) and middle-aged housewife Carol Aird (Cate Blanchett) meet at the department store where Therese works, exchanging a few torrid glances but no overt declarations of romantic interest. Carol leaves her gloves on the counter—perhaps intentionally—and subsequently finds an excuse to bring Therese to her house, providing her with a grand tour. At this point, the two women haven’t so much as touched one another, much less voiced their attraction; both are models of Eisenhower-era propriety. Carol has removed her shoes, however, and when she hears her husband, Harge (Kyle Chandler), walk in the door, she immediately scrambles to put them back on, before he can see her with Therese in her stocking feet. Again, nothing is made of this—it’s shown at a distance, uncommented upon, mundane. But like the man, riding the elevator with his wife, who removes his hat when a pretty girl steps on (courtesy of Raymond Chandler, discussing visual storytelling in a letter to his agent), it speaks volumes all the same.

It’s also a slightly different approach to the ’50s for director Todd Haynes, who previously explored the era’s spirit-crushing repression in 2002’s hugely acclaimed Far From Heaven. Haynes conceived that film as an homage to Douglas Sirk’s melodramas, crafting a heightened, ultra-lush look and eliciting performances that were gently italicized. Carol feels much more modern, even as it remains faithful to its era. The imagery is no less breathtakingly gorgeous (Haynes worked, as he has ever since Heaven, with cinematographer Edward Lachman), but there’s an urban sheen in place from the very first shot: an abstract pattern that’s revealed as a sidewalk grate, from which the camera tilts up to take in an evocative view of midtown Manhattan at night. And while Therese and Carol’s love still dare not speak its name, their desire to shout it from the rooftops could scarcely be plainer. Highsmith’s novel acknowledges the near-impossibility of a lesbian romance at the time, but she was determined to avoid the usual tragic ending. Haynes honors her intentions and then some, creating a period piece that seems to be aware of the shifting landscape we currently inhabit and desperately trying to arrive at that place by force of will.

Credit much of that force to Carol’s two leads. Because she’s a two-time Oscar winner and is playing the title role, Blanchett received the lion’s share of the attention when the film premiered at Cannes last May; the Cannes jury, however, chose instead to award Best Actress to Mara. (In one of the most blatant instances of category fraud on record, The Weinstein Company is campaigning Mara for Supporting Actress, even though Therese is as much the film’s protagonist as Carol is, and arguably more so.) Ideally, they’d be recognized jointly everywhere, since their work is essentially symbiotic. As is often the case with Haynes’ films, Carol has been deemed overly chilly by some, but demonstrative and deeply felt aren’t always the same thing, and this unsentimental but intensely passionate relationship serves as exhibit A. The visible jolt of electricity that courses through Carol’s body the first time Therese casually touches her hand, as they sit opposite one another at a diner, having a bland conversation, communicates more than any number of Nicholas Sparks-style kisses in the pouring rain. (When the two finally do have sex, though, Blanchett’s career-long aversion to nude scenes does seem to get in the way of what Haynes wants.)

Indeed, Carol’s central relationship is so compelling on its own—among other complications, Therese had previously identified as straight and has a boyfriend (Jake Lacy)—that the social-problem aspect, while undeniably accurate, feels comparatively pro forma. When Harge attempts to win sole custody of their child by attacking Carol’s moral fiber, solely on the basis of her affairs with women (she’d previously been involved with a friend, played by Sarah Paulson), some mild speechifying ensues, making the movie feel a bit less rapturous and more like a PSA promoting equality. But that’s a quibble, as is any objection to screenwriter Phyllis Nagy borrowing a key framing device from the 1945 masterpiece Brief Encounter (ill-advised only because the list of screen romances inferior to Brief Encounter includes literally every screen romance ever made, so why call attention to that?). Haynes has pulled off something remarkable here, without a trace of winking or archness. It’s been a long time since the movies have seen a fuse of pure ardor burn this slowly and steadily, leading to such an unexpectedly moving explosion of resolve.