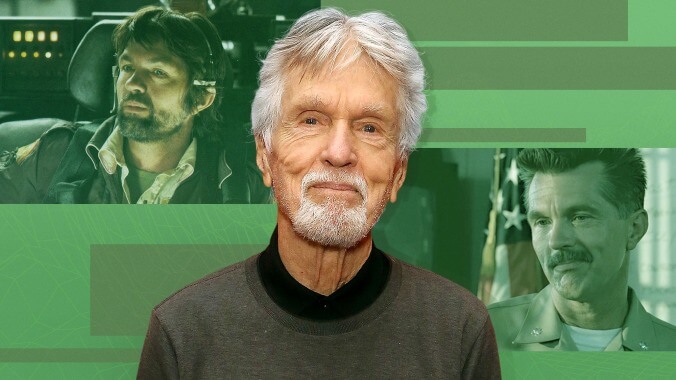

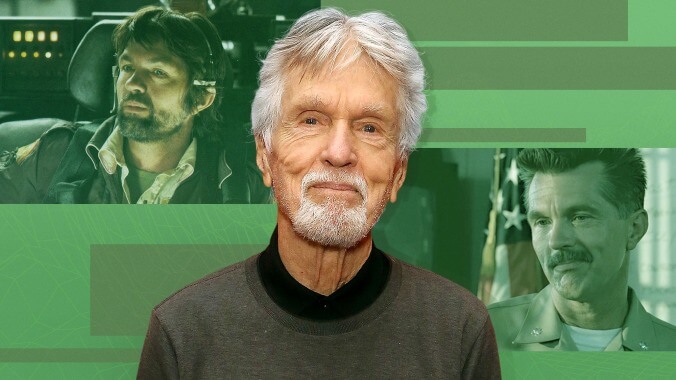

Tom Skerritt tells us the funniest thing he ever witnessed on the Alien set

Image: Photo: Walter McBride/Getty ImagesGraphic: Jimmy Hasse

Tom Skerritt has starred in some of the most iconic movies ever made—M*A*S*H, Alien, Steel Magnolias, Top Gun. He also won an Emmy in 1993 for Outstanding Lead Actor in a Drama Series, playing the sheriff of a small town plagued with a variety of bizarre crimes in the acclaimed David E. Kelley show Picket Fences. The now 85-year-old Skerritt is the type of actor you know as soon as you see him, who has never really slowed down in his decades-long career. A few years back, he returned to his native Seattle, where he started Heyou Media, a digital media company focused on storytelling and classic films. He’s even given a TED talk discussing how he uses storytelling to help veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Skerritt still doesn’t mind revisiting his own classic films. He recently visited Chicago for a showing of Alien, in honor of the film’s 40th anniversary, and we got the chance to sit down with him briefly to go over some highlights from his extremely long IMDB page.

Tom Skerritt: As it happens, one of the most memorable things in my career was making Alien. I recognized we were making something extraordinary. But what comes to mind is what surrounds that body of doing it—watching them doing it.

One day I didn’t have to come to work until the afternoon, so I came right as they were breaking for lunch, opening the big stage doors. And out walked the crew, and then the alien character, who was a 7-foot-1 guy. The head was off, and he’s walking with the wardrobe lady, who’s about five-two. And they’re having a genuine British economy conversation, and holding the tail of the creature was the flamboyant wardrobe guy, his white scarf being blown, walking along, and the creature is wearing these very bright blue Adidas tennis shoes. And I really wish I had a photo. I didn’t have an iPhone, nor did I have a camera, so it sticks in my mind.

That, and one other thing about one of the actors—one of the American actors had to warm himself up by kind of getting his emulsions going before a scene. It was right after lunch: “Oh, you English, you’re so quiet, standing around, why don’t you mess around and cover your ass with your hands and shake it up?” I get it; I don’t necessarily do that, but I understand it. I honor it. But it was going on for a little bit. All right, shoot. And two crew guys, Englishmen, in front of me with their backs to me—one of them turns to the other and says, [Adopts English accent.] “Isn’t it grand being English?” I love British humor. That was just great. Just very quietly, being cheeky, this guy: “Isn’t it wonderful being English?” [Laughs.]

The A.V. Club: Your career was already decades-long by that point. What about Alien made you know that it was going to be the cinematic juncture that it is?

TS: Ridley Scott. I was given the script, and I read it, and $2 million was the budget. They had no director or anything else, and I looked at it and I thought, “Well, it’s solid, but this budget…” I thought maybe it would do well, jokingly, but I couldn’t really wrap my head around this thing for $2 million. What I did like was that there was a woman—a strong woman that rises and does that with a lot of chutzpah.

I liked that idea. I’d done Turning Point, which was about all these difficulties that women had, how strong they are, and so that’s what I liked about it. But I thought, “Ah, I don’t know. I have to think about this.” But it happened that a few weeks before, I’d seen The Duelists, that Ridley had directed. I only remembered his name because I thought, “Whoever this guy is”—and I’m told it’s his first movie—“this is unusually competent filmmaking.” And a few weeks after, they called me up and said that Ridley Scott was going to direct it. So now it’s a $10 million budget and Ridley Scott’s going to do it. I said, “I’m in.”

AVC: Is it more of a science fiction movie or a horror movie to you?

TS: It’s neither. Honestly, I’ve never categorized—I’ve done such a variety of films. And it turns out now that they’re classics, which is another genre. So that’s not conducive to a movie star status, in terms of, “Oh, that’s Tom Cruise”—because you do basically have to play the same character in most of your films. Tom is a good actor and he’s a lovely guy, and he knows how to do that work. I’d done theater and I wasn’t looking to be an actor to begin with.

AVC: You thought of yourself more as a director, right?

TS: Writer-director, that’s what I wanted. I saw Citizen Kane and I said, “That’s what I want: I want to write and direct. But I have to know how to act to write and direct.” And that was scene acting, and so on and so forth. So the whole thing is just, to me, a fairy tale now. Fifty years of it. And that’s how I see it. There are much better actors than I am. And I think more about those films that I think really were a stinky performance. About those films where I thought my acting was terrible.

AVC: Is there one that comes to mind?

TS: No, one doesn’t come to mind. It’s not a matter of not mentioning it—I’m just talking about the self-questioning that goes on. Perhaps insecurity from when I was a kid. Nobody ever told me anything but be a factory worker, you know?

That’s a frame of reference that was turned around by school—when I was 5 to 10 years old, the school had creative programs. And I had these tiny experiences. In my creative program, I was being guided by a teacher at a time when my imagination was just beginning to bud. So when your imagination first comes at that age, you’re a little afraid, you know—there’s nobody to change your diapers anymore. But if you had guidance from someone who can lead you to this moment or have this emergence—and the curiosity comes—and they never said “no,” never said “bad.” They said, “Well, maybe if you did this. Maybe if you did that.” They’re adding to you in a way that you begin to see, “Oh, that does look more like a house,” than a crumbled castle.

Small things. Going to creative venues—they used to take us to the world’s greatest conductor—symphony conductor of the 20th century, which meant nothing to me. Come alive well into his eighties—I never thought he could get out to the podium because he was physically challenged—and suddenly he’s 30 years old, pulling this sound out of the air in a way I could never do. It made me understand there was something more than what appeared at first.

Seeing the Detroit Institute Of Art—they’d bus us in to the museum. It didn’t mean anything to me then, but Rodin’s sculpture The Thinker is out front of that—and I remember looking up at that—maybe I’m 7, 8, 9—and saying, “Okay: naked guy sitting on a toilet without the sports section. I’ve got nothing to read.” Which is funny as hell, but that’s my frame of reference. And, going into that thing, I see a little sign on the desk where the people are buying tickets—this thing says, “There is no right or wrong or bad or good—only thinking makes it so.” So I’m thinking, I’m trying to put this together with what I’ve just experienced out there. And that kind of stuff, how a piece of art affects you appreciably by the experience your frame of reference has, which sorts it all out, gives you intelligence, more favorable items, which leads you to influencing your instinct to drive your impulse to be creative. Or anything! And that’s the gift of my lifetime—is that reward.

AVC: You look at your résumé, and you just never stopped. You did Ice Castles, and Alien—around the same time—and then you would do a guest star role on TV—you’d do Cannon. You were constantly working.

TS: I had kids to support. I had to make a living, you know. You have to do what you have to do—I had three kids. I had to raise the kids myself, so it’s a very delicate balance. And that’s part of my appreciation at this time in my life to know where I’ve been and what I’ve gone through—it turns out it’s given me an understanding about taking the risk of possibilities and testing the audacity of your imagination. I’ve been given a world of opportunity to let my frame of reference inform my intelligence—right or wrong, I realize it’s what I believe. It goes back to that Shakespeare thing: There’s no right or wrong or bad or good—your thinking makes it so.

AVC: Do you remember anything about filming that?

TS: That was a nice film. It was very cold—we were in Minnesota. I think it was at that time that I received the script for Alien, by the way. I was in a hotel, I remember now—you reminded me—it was when I was doing Ice Castles. And that was working with Colleen Dewhurst, who was wonderful. I was always knocked out by the actors I worked with. I’d think, “Wow, I got to work with this person and that”—I never could imagine myself as a movie star because that’s not what I wanted to do. I just wanted to be able to support my kids. I just wanted us to get by. I didn’t want us to have to move into a trailer park camp because I couldn’t afford any rent, you know? All those things were going around in my head and meanwhile I’m getting these therapeutic possibilities of doing this creative stuff given what I was given emotionally.

AVC: You’ve mentioned that Robert Altman was a big influence on you. Do you consider M*A*S*H your breakthrough role?

TS: I don’t think I’d be in the business if it wasn’t for him. I mentored with him right out of college. He was a TV director then. We were having a conversation, and he said, “Well, why don’t you come out—I’m directing a TV show; you can come over and watch.” I thought, “Great.” So I mentored with him for several years. And then he called me up and said, “I’ve got a movie to make and I’d like you to be in it.” I would do anything, because he was teaching me stuff that I understood was significantly unlike most of the things that I had preconceived notions I had. He was not a Hollywood guy.

But I liked the way he was with the crew—he made them engaged. He gave them something in some small way, whether it was intentional or just the way he was—he was open to suggestions. And sometimes they were the worst things you could imagine they’d come up with. But he would never say, “That’s not going to work.” He’d just say, “Geez, thanks.”

AVC: That no good or bad thing—it’s the same thing.

TS: There’s no good or bad. As Altman pointed out, that makes me think, “If he hadn’t said that, I wouldn’t have this idea.” You know, it’s what you get and make of it. All of our life, it’s what you make of it. Sometimes that makes me cry—just to be able to have this feeling about what I do. It’s pretty remarkable. I honor that simple stuff. It’s easier for me to feel emotional about. I feel like I’m a football player—a really good open field runner, getting through the defensive line, and not getting tackled running through to a touchdown. You know, the glory that you felt doing that—I did it once. Just almost scored a touchdown one time—fumbled and got tackled just before. [Laughs.] Tiny things!

AVC: So, on M*A*S*H, with Donald Sutherland and Elliott Gould, were you guys improvising a lot? It’s such an enjoyable movie to watch, you must have been having fun filming it.

TS: That’s what the audience felt. And that’s what I knew about Altman, because he did things that engaged the audience in kind of awkward ways sometimes, you know? Is that recess? It’s overlapping. I knew what he would do when I got into that.

Donald and Elliott were not so inclined to appreciate that—they were kind of on the rise. Bless their hearts—they kind of isolated themselves from it somewhat. And that isolation, Altman—in a way, he’s moved by what other people are doing, and he adjusts to that. Rather than saying, “No, I want you to be this way”—I don’t remember specifically what Donald and Elliott thought, except it wasn’t the standard way they were used to, and that’s all. So I was often finding myself in the position of [listening to] complaining to Altman about his approach, and Altman saying he’s annoyed by these guys, and trying to play like I was the referee in some ways. And it turned out differently. But I thought it was going to turn out that way, because we were all enjoying ourselves in a way that I told them, a couple of weeks before we finished shooting, “We’re never going to have the time we’re having now, ever again.”

And none of us really ever have had that kind of experience. And that was a thing that all actors loved about working with Bob: He just makes you feel without saying it, you know? “I don’t know—try it out.”

AVC: You’re part of the creative process.

TS: The final rewrite of the script is the final edit. And that’s what Altman did [with M*A*S*H]. He didn’t do the script for it, but he did all the stuff that came out of the inspiration, and then he edited it. And edited it. And edited it. The studio hated it. And the writer wanted his name taken off of it. It wins an Academy Award [for Best Adapted Screenplay], and the studio is financially saved because of it. So you don’t know. You feel it.

We never intellectualized this thing—I don’t know how it happens. All I know is you’ve got to just trust your people. And if they’re not really—if they’re way off, they’re not really giving themselves to the impulse. A lot of actors—a lot of people—do not give themselves to take the risk of possibility. Even taking a job if you’re trying to build a career—you’ve got to sometimes think about how this is going to affect that career. But I could never do that—I had kids to support. I had to make a living.

AVC: So that’s why you took a TV series like Picket Fences?

TS: Oh, no. Picket Fences, you’ve got David Kelley writing. No. That was no waste of time doing that. That was extraordinary—again, that was one of those things that I thought, “Oh, wow, I don’t know about this, but…” It was written by the best writer on television. That was the magic and brilliance of it. Because I wasn’t trying to do a series, but then they said Kathy Baker was going to do it, and I thought, “She’s fabulous—what do they want me for?”

And I went in and I met—we talked with David. And I thought, “Whoa! Once again, I’m in something special.” When you know, you feel it. Can’t lay it on any other way. So, wound up four years with 14 Emmys, and, at the time, it was considered the best show on television. Never really had great ratings because it was very intelligent writing. Not that we were so great—it was great. It was like Mozart writing a symphony: never corrected a note. David rarely ever had to do any rewrites. He could whip these things out in a day. And I got to direct some of these things. And it was just like, “I could play with this all day.” It’s all been fun.

AVC: Was Top Gun another instance where you thought, “Wow, this is going to be huge?”

TS: Yeah. I read that, and I knew Tony Scott because of Ridley, and I knew what he could do, so this is one film I really worked to get into, because I knew the film was going to work. It’s not about the role—it’s about all the stuff that goes into building a great structure. It starts with the script—inspiration’s in the script—if it’s there and you’ve got the right director, that’s—the intensity of the inspiration of the writer, less or more, if there’s inspiration there, a good director can pick that up and make it his own, which is what Altman did. What [Hal] Ashby did. What Ridley does. It goes beyond anything I saw in that $2 million script I read. Just having that instinct, that impulse.

AVC: Do you think Tony Scott just took it to the next level with Top Gun?

TS: Oh, yeah. Very easily, he did. Very much schooled by his older brother. And he was magic. Again, he makes it look so easy to do.

AVC: Are you the uncredited motorcycle cop in Harold and Maude as a favor to Hal Ashby?

TS: I knew Hal Ashby prior to that. I even read it when it first came in when they were making the offer. And he’s making it, and the guy who was the cop was another actor who went out of the shot, the kickstand’s down, it throws him, and he broke his leg.

I ran into Hal and said, “Hey, how’s it going?” “Man, today it was tough.” Because he was always a good guy—didn’t want people hurt, and this guy broke his leg, and I said, “Shit, I can do that.” So it gave me a reason to come up and continue mentoring with Hal Ashby.

AVC: You’re basically one of the the only men in Steel Magnolias, but your scenes and banter with Shirley MacLaine hold up so well. Then you got to match up again with Sally Field in Brothers And Sisters. What was Steel Magnolias like?

TS: Well, Shirley I had worked with in The Turning Point. She was my wife, and now she was the neighbor. To work with them and watch how they work—always better than what I was doing. I can be better. We can all be better. But that’s the thing about life.

AVC: But your affection for them really comes through in that movie and Turning Point.

TS: Maybe it was adoration. Because I think those ladies are just… wow.

GET A.V.CLUB RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Pop culture obsessives writing for the pop culture obsessed.