Top Gun is the sleekest, horniest recruitment ad of the 1980s

Midway through Top Gun, the highest-grossing movie of 1986, there’s a scene where the film briefly abandons all sense of narrative and plummets into a sort of ecstatic erotic delirium. Tom Cruise’s Maverick and Anthony Edwards’ Goose, our two heroes, play a game of glistening beach volleyball against Val Kilmer’s Iceman and Rick Rossovich’s Slider, their blood rivals. Director Tony Scott cuts the scene to a Kenny Loggins song called “Playing With The Boys.” For three minutes, the film takes a pause and just admires these oiled-up bodies, letting them flex and slap and grunt and shine. If you saw Top Gun at any kind of formative age, this scene is seared into your memory.

“Soft porn.” That’s what Tony Scott once called that scene. In a DVD interview decades later, Scott admitted that he had no particular vision for it: “I knew I had to show off all the guys, but I didn’t have a point of view… so I just shot the shit out of it. I got the guys to get all their gear off, and their pants, and sprayed them in baby oil.”

There’s really no narrative purpose for that volleyball scene. Seen from any logical angle, it’s absurd. (Cruise plays volleyball in jeans, and the sheer ball-sweat implications alone boggle the mind.) Within the film’s storyline, the volleyball scene reaffirms Maverick and Goose’s rivalry with Iceman and Slider, but it’s not like the movie hadn’t gotten that across already. It also makes Cruise late for his date with Charlie, the sexy flight instructor played by Kelly McGillis. This leads to the scene where Maverick shows up to this lady’s house and immediately asks to use her shower, perhaps one of the weirdest romantic power moves in cinematic history. But the volleyball scene doesn’t have to work within the narrative. It merely has to exist.

Tony Scott had only directed one movie before Top Gun, and that was The Hunger, a gothy and vaguely arty 1983 vampire flick that starred Catherine Deneuve, David Bowie, and Susan Sarandon. Scott didn’t get the Top Gun job because of The Hunger. He got the job because he’d made a 1984 Saab commercial where a car races along a runway, underneath a fighter jet. In that ad, Scott fetishizes the hell out of the plane—the cone of its nose, the shimmer of its jetstream, the fire coming out of its tail. Today, that Saab commercial looks like a Top Gun audition reel. And perhaps Scott’s real innovation in Top Gun was to eroticize the pilots just as much as the planes.

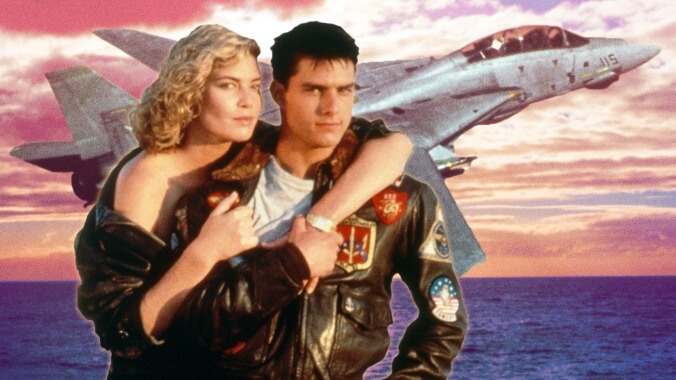

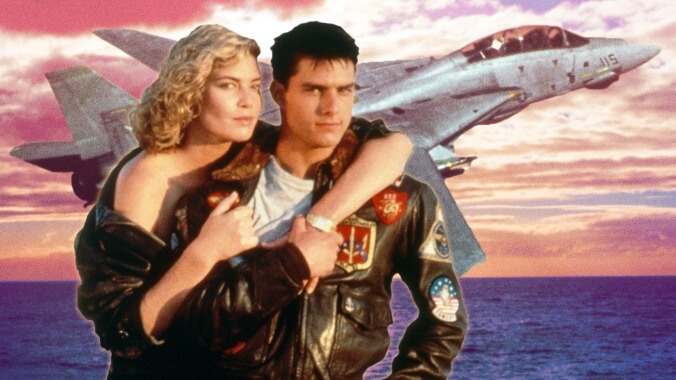

Top Gun is a beautiful movie. Tony Scott shoots everything possible in golden-hour light—insane red-streaked sunsets, faces silhouetted against skylines, sweat glinting off of every face, steam billowing everywhere. The film has a pulse, thanks to Harold Faltermeyer’s mythic synth score and the percolating Kenny Loggins and Berlin songs that Giorgio Moroder produced. When planes are in the sky, twirling and spinning and nosediving, physics almost cease to exist. It’s the most aesthetically arresting propaganda film ever created.

Producers Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer got the idea for Top Gun from a 1983 magazine article about the culture of fighter pilots at the Navy’s Fighter Weapons School at Miramar, California. In making the film, they got the full cooperation of the U.S. Navy, who let the producers use their ships and aircraft for virtually nothing. In return, the Navy got full script approval. That’s why Goose dies in an ejector-seat accident rather than the planned mid-air collision. It’s why, in the opening sequence, Cougar doesn’t die by crashing into an aircraft carrier deck. And it’s why the picture’s geopolitics are so maddeningly vague. Are the pilots fighting the Russians at the end? Why is there a military crisis in the Indian Ocean? What are they protecting? Thanks to the Navy’s story input, we don’t know. And thanks to Tony Scott’s visual firepower, we don’t care.

Top Gun makes the Navy look like the coolest possible place to work. Scott’s camera worships Tom Cruise, who wears the hell out of jeans and bomber jackets and aviator sunglasses, preening and posing and emitting intense sex-symbol vibes at all times. Most of the narrative energy goes toward establishing the culture of Maverick and the other young fighter pilots at Miramar. They’ve got rituals and hierarchies and cool call signs. (I like how they all have their own individualized helmets, as if there’s a graphic designer somewhere in charge of translating those call signs into logos.) When Maverick and Goose pull the impossibly dorky pick-up stunt of singing a rhythmless “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling” to a girl in a bar, all the other pilots somehow intuit exactly when they’re supposed to come in on the backing vocals.

Most of Top Gun is structured as a sports movie. The villains aren’t the pilots of the Russian-built MiGs. Those enemies are too mysterious—their faces always masked like the TIE fighter pilots in Star Wars, their motivations utterly irrelevant to the machinations of the plot. If there’s a villain, it’s Iceman, whose only real sin is acting like a bit of a pompous dick. (Every time Iceman criticizes Maverick for unsafe showboating, he’s absolutely right.) Top Gun isn’t a war film. It’s a story of high-school machismo with added military firepower.

In the context of 1986, there’s something fascinating about the way Top Gun depicts masculinity. Many of the year’s other big hits are all about real men’s men trying to function in feminized cosmopolitan culture. Crocodile Dundee, the No. 2 movie at the 1986 box office, was an out-of-nowhere smash that earned nearly as much as Top Gun. It’s a low-budget Australian comedy about a charming outback bushman who proves perfectly capable of handling the urban jungle of New York City. (Thanks to scenes like the one where Paul Hogan grabs a drag queen’s nuts in front of a cheering bar crowd, it’s virtually unwatchable today.) In Back To School, Rodney Dangerfield has to teach his uptight college-boy son how to loosen up and party. Oliver Stone’s Platoon, a Best Picture winner and a legit blockbuster, is the flip side of Top Gun, a Vietnam picture that makes military life look like absolute hell. It’s also a tale about the dark side of masculinity, as war gives Tom Berenger’s magnetic psychopath all the room he needs to become a senseless killing machine.

The Tom Cruise of Top Gun isn’t like Paul Hogan or Rodney Dangerfield or Tom Berenger. Maverick brings a sarcastic peacocking swagger on his mission to prove his own mastery and dominance. For the first half of the movie, he acts like everything is funny. He has a supernatural ability to make that one guy repeatedly spill coffee all over himself. But Maverick is visibly driven by sadness and insecurity; the movie works to point out that his arrogance is a front. He feels responsible for his best friend’s death, and the film leaves open the question of whether it’s really his fault. People keep bringing up his dead father. He’s lost and haunted and immature. He’s not a king of the jungle.

Further complicating matters: Top Gun is one of the most homoerotic spectacles ever to come out of Hollywood. Cruise has absolutely zero sexual chemistry with his ostensible love interest; every time he kisses Kelly McGillis, he seems like he’s trying to eat her face. (Watching Top Gun back-to-back with 1985’s Witness is really something. One movie shows Kelly McGillis portraying believable horniness for her co-star. The other does not.) But Cruise pulses with energy in every locker-room scene. Eight years after Top Gun, Quentin Tarantino showed up in the otherwise-unremembered indie film Sleep With Me to rattle off a frenzied party-scene monologue about how Top Gun is really “a story about a man’s struggle with his own homosexuality.” His quotes aren’t quite right, but his theory has merit.

American film audiences had been absolutely primed for the sexed-out, spectacular delirium of Top Gun. In the years leading up to the film, producers Simpson and Bruckheimer had hit the zeitgeist with 1983’s Flashdance and 1984’s Beverly Hills Cop—two proudly shallow pictures that got over on coked-up quick-cutting and visual flash. MTV had helped shape the visual imagination of audiences, and Bruckheimer and Simpson, more than anyone else, had figured out how to tap into that. In Tony Scott, they found their greatest collaborator. Scott went on to work with Bruckhemer and Simpson a bunch of times: Beverly Hills Cop II, Days Of Thunder, Crimson Tide. And Scott also pretty much invented the dizzy, disorienting blockbuster style that future Bruckheimer collaborator Michael Bay would turn into something like sheer abstraction in the ’90s.

And then there’s the military. In the early ’80s, the Army had been a backdrop for the massively successful fish-out-of-water comedies Stripes and Private Benjamin. Both of those films told stories of baby-boomer hedonists who fall ass-backwards into military service, slump their way through boot camp, win over their hardass commanding officers, and eventually distinguish themselves in battle. The Bill Murrays and Goldie Hawns of the world were no longer protesting against the military. Instead, they were bending it to their will.

An Officer And A Gentleman, one of 1982’s biggest hits, used a similar backdrop for a pretty great love story. Richard Gere—just as hot and just as fetishized as Tom Cruise in Top Gun—is a go-nowhere drifter who makes up his mind to become a Marine aviator and, along the way, falls for Debra Winger. Like Cruise, Gere is haunted by the deeds of his serviceman father. (Cruise’s father is mysteriously dead; Gere’s is embarrassingly drunk.) Like Cruise, Gere radiates cockiness and gets under the skin of commanding officers. Also like Cruise, he looks almost inhumanly good on a motorcycle.

Top Gun takes that cinematic trend and transforms it into a militaristic Reagan-era fever dream. Tony Scott tells that story through myth and montage. The film’s aerial footage is breathtaking. (Scott shot actual stunt pilots doing incredible things, and one of those pilots, the cameraman Art Scholl, crashed and died during filming.) Its scenes on the ground, though often clumsy and underwritten, are just as gorgeous. The story is simple and elemental. Arrogant young Maverick loses his best friend, goes through a crisis of confidence, gets through the other side, and becomes a military hero in the closing minutes, saving his school rival and, for all we know, either causing or averting global war. (The actual love story is fully tacked-on, and Scott treats it as, at best, a distraction.) There’s nothing fancy about the story, but Scott makes it sing.

The supporting cast is both weird and great. Anthony Edwards brings a goofy charm that gives the story a humanity it might’ve otherwise lacked. A very young Meg Ryan, in her few scenes as Goose’s wife, really helps there as well. Val Kilmer gives a deeply strange performance while also looking like an action figure. Tom Skerritt and Michael Ironside bring grizzled toughness and convey the stakes. James Tolkan, the principal from Back To The Future, gets to be the bald guy who chews out the strutting young heroes in the two biggest movies of the mid-’80s. Tim Robbins silently looms in the background of the final celebration scene, raising the question of how he ever managed to fit into a fighter cockpit.

The talent and craft that went into Top Gun is undeniable. It’s effective blockbuster filmmaking, and it was an effective propaganda tool, too. The Navy set up recruitment stations in some of the theaters that were playing the film, and it reported a 500% bump in enlistments in the years after Top Gun came out. In some ways, that makes Top Gun detestable. The film really does glorify the adventures of America’s war machine, and anyone who distrusts that institution should have nothing but contempt for it. But I can’t hate Top Gun. It’s too awesome to hate—too good at its detestable job.

Sometime in the near future, we will get to see Top Gun: Maverick, the long-delayed sequel that was still in pre-production when Tony Scott took his own life in 2012. The trailer, now nearly a year old, is a small masterpiece. Top Gun: Maverick was supposed to hit theaters this summer; it’s now scheduled for December. It seems to feature Tom Cruise flying fighter planes for real. The world of 2020 is very, very different from the world of 1986, and the climate right now is not exactly a great one for the project of American exceptionalism. And yet I would probably blow a car payment to watch Top Gun: Maverick in a theater right now. This particular form of absurdist propaganda has not lost its grip on my imagination.

The runner-up: It’s one of my favorite movies, but I’ve already written a column about Aliens, the No. 7 film at the 1986 box office and a very different portrait of militarism in action. So instead, I’ll use this space to highlight the John Hughes comedy Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, the year’s #No. 10 earner. Bueller makes no sense at all; it’s simply not possible to do all the things that Matthew Broderick and his friends do over the course of one sunny Chicago day. And yet the movie works as pure slapstick and as dream-logic reverie—one kid getting to outwit the entire world and live every other kid’s fantasy.

Next time: Men! Take care of a child! Can you believe it? Outrageous! Diapers and everything! It’s Three Men And A Baby, and it’s the biggest hit of 1987. I don’t even know, dude. We’ll figure this one out together.

GET A.V.CLUB RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Pop culture obsessives writing for the pop culture obsessed.