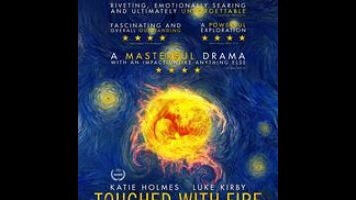

Touched With Fire starts as a love story and turns into a lecture

It wouldn’t be entirely accurate to call Touched With Fire an opposites-attract romance; both members of its central couple are poets, both suffer from bipolar disorder, and they meet at a psychiatric hospital where neither of them have precisely intended to stay. But Marco (Luke Kirby) and Carla (Katie Holmes) approach their illnesses very differently. Marco tries leaning into his manic episodes, insisting that it makes him experience the world with deeper, more vivid feelings, decrying medication as the real problem. Carla is more self-conscious, showing up at her childhood home in the middle of the night to ask her mother (Christine Lahti) when it was, exactly, that her mental health problems first emerged. Like any number of romantic heroes, they get on each other’s nerves at first, during a group therapy session. But a few days later, they’re each other’s whole world.

Touched With Fire follows Marco and Carla on the individual paths that land them in the same therapy group, and continues as they attempt to build a life together, often against the advice of their families and doctors. The film was written, directed, co-edited, and scored by first-timer Paul Dalio, a protégé of Spike Lee, making Fire the rare 40 Acres And A Mule production not directed by Lee himself. It’s obviously a personal story for Dalio, who has also dealt with manic depression and apparently used to perform at rap battles under the name Luna, a detail reassigned to the Marco character here.

Dalio has a talent for visualizing his characters’ mental states. In the opening scenes, he goes handheld, but the effect isn’t the typical shakiness; it feels more wobbly, like the camera is teetering on the edge of something. That expressiveness continues and changes with the story. When Marco and Carla wind up in the psychiatric hospital, the camera stays more locked down; when they begin their relationship, staying up late together and conspiring in circles, it floats along with them in a reverie. The film’s evocations of this state aren’t all behind the camera. Holmes channels the nervous energy that has hummed behind her best performances into a character whose anxieties have real yearning and weight. Kirby, for his part, sounds in his quieter moments a bit like Mark Ruffalo (high praise for any actor toiling away in an indie).

Yet as personal, well-performed, and sometimes lyrical as this material is, Dalio also has a peculiar way of making it all play like a public service announcement—like a feature commissioned for a mental-wellness convention. Touched With Fire takes its title from a nonfiction book by Kay Redfield Jamison that discusses the links and relationships between bipolar disorders and the creative mind. This film isn’t an adaptation, per se, but that doesn’t stop Dalio from enlisting Jamison to cameo as herself in a scene where she talks to Marco and Carla about whether medication will dull their creative instincts. Marco thinks so, Carla disagrees, and Jamison generally and quite reasonably sides with Carla—but what is a scene like this doing in a movie that’s not about a Steve Harvey book? This supposed focus on the artistic dimension of mental illness is especially ill-suited to a film willing to elide not just practical questions (like where Marco and Carla get money to rent an apartment together in New York City) but artistic ones, too (like what kind of art they actually produce, or want to produce). The fact that Carla is a published poet doing readings at mainstream bookstores breezes by matter-of-factly; the movie doesn’t seem to understand or care how rare this is.

As it turns out, the romantic story doesn’t bear any more scrutiny than the movie’s glancing examination of artistry. A bunch of scenes that make Carla and Marco’s life together look like a Terrence Malick movie convey the feelings of their relationship, but not the everyday details. As the movie goes on, the dialogue scenes get stagier and the confrontations feel more like case studies. The film’s self-importance peaks in its closing moments, as it scrolls through an off-puttingly lofty dedication to a who’s-who list of notable artists who are mentioned in Jamison’s book. The implication is that they were all bipolar as well, though the dedication falls short of making that statement (just as it falls short of saying much about the act of artistic creation). In this movie’s hands, it seems like an oversimplification, whether it actually is or not. Touched With Fire turns into such an earnest awareness lecture that its emotional core winds up inspiring a kind of cynical distrust.