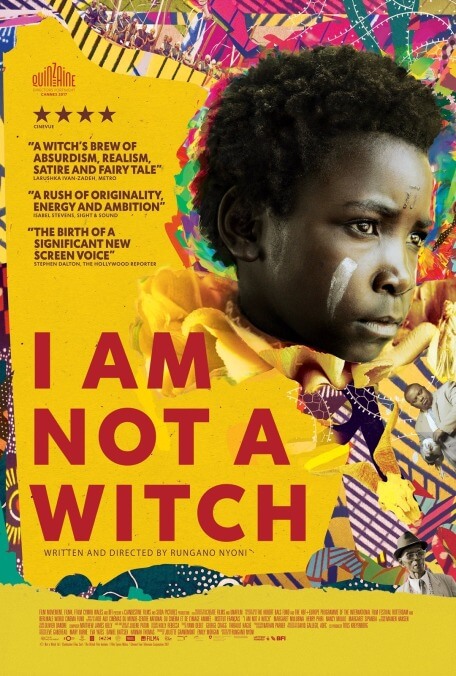

That’s what a guide tells a group of gawking tourists snapping photos with their smartphones in the opening scene of the film, the first of a series of collisions between traditional belief and modern technology that highlight the darkly comedic side of life in Africa today. Maggie Mulubwa, a nonprofessional actor who was spotted playing with her friends near the lakeside town of Samfya, is a revelation as 8-year-old Shula, an orphan who happens to be standing nearby when a woman trips and spills a bucket of water outside of a dusty rural village, and who is accused of witchcraft as a result. Word of her trial—an absurd affair where locals recount dreams they’ve had about the young witch, as a bored and skeptical policewoman looks on—reaches Mr. Banda (Henry B.J. Phiri), a government official who makes his living off of exploiting belief in witchcraft via rituals-for-hire and the tourist trade.

Delighted to have such a photogenic new charge, Banda takes Shula to a witch camp, where she’s outfitted with her ribbon and some traditional garb. Soon, Banda is traveling the countryside with Shula in tow, renting her out for magic-assisted trials and rainmaking rituals in exchange for money and bottles of gin. Their journey through the different levels of Zambian society goes as far as an appearance on a TV talk show—one of the funniest scenes in the film—where Banda responds to a caller condemning his exploitation of a child with a muttered, “That’s total misuse of freedom of speech.”

While the people around her undoubtedly believe she’s a witch—or see an opportunity to exploit that belief—it’s not clear whether Shula ever believes in her own powers, or, indeed, if she has any. (Although I Am Not A Witch stops just short of magical realism, there are a few pointed coincidences.) For much of the film, Mulubwa remains stoic, only the occasional pouting lip or single tear betraying her true feelings, especially after she figures out that passively refusing to participate in Banda’s schemes is the best way to get out of them. The only time we see her smile is in the presence of the other witches, kindly, good-humored older women who form the Greek chorus of the piece.

Nyoni has emphasized in interviews that I Am Not A Witch is a fairytale, not to be taken literally—the ribbons, for example, are a detail that was invented for the film. But it’s grounded in reality, not only in the sense that the witch camp where the majority of the story takes place is based on real places Nyoni visited in Ghana and Zambia, but also in the film’s bone-dry, gently absurdist sense of humor. In an interview with Little White Lies, Nyoni says, “I wanted to show Zambian humor and how we deal with tragic events, which from the outside may seem very inappropriate.” To some, maybe. But Nyoni’s modesty is unnecessary: I Am Not A Witch fits right in to the cringe-comedy tradition, albeit on the more formally rigorous end. Think the deadpan comedy of Ruben Östlund, or the sublime awkwardness of Toni Erdmann.

Superimposing creative license onto complex systems of belief sometimes makes it difficult for outsiders (like this reviewer) to tell which is which; given how firmly Nyoni’s tongue is planted in her cheek throughout, one suspects this may have been intentional. And the film never condescends to the belief in witchcraft, or implies that such a belief is shameful in itself. Not that those beliefs go un-interrogated: The film’s feminist streak is very strong, and Nyoni condemns the impulse to blame all of society’s ills on rebellious or otherwise unusual women, as well as the corruption of men like Banda, strutting around in his three-piece suit paid for by the exploitation of an innocent girl. It’s less the beliefs that are the problem, and more their cynical manipulation by bad-faith opportunists.

Nyoni’s direction—for which she won a BAFTA award—is bold and ambitious, and challenging at times. She prefers long, unbroken wide shots and slow zooms inward, reserving most of her closeups for Mulubwa’s ever-observant face. The music selections are a bit flashier, blaring selections from Vivaldi and Schubert over particularly ironic scenes in a bombastic fashion reminiscent of European art film. If anything, like many auteurs, she could benefit from a producer intent on tightening the narrative; the film begins to get a bit repetitive in its final third, before an abrupt, haunting ending that, whether they love it or hate it, is sure to get audiences talking. Nyoni is clearly confident in her vision and the story she wants to tell, and in her capable hands, the result is spellbinding.

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)