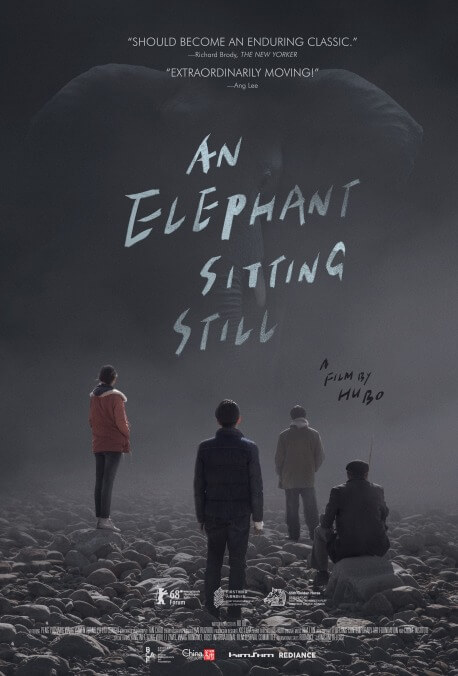

Tragedy looms over the epically depressive debut/swan song An Elephant Sitting Still

Roughly midway through hour one of the four-hour Chinese anti-epic An Elephant Sitting Still, one of the main characters, a high school student, passes another kid in the hall. “The world is a wasteland,” this other student says, apropos of nothing whatsoever. At the time, this grim non sequitur merely seems weird; three-and-a-half grueling hours later, though, it’s abundantly clear that those words serve as the film’s abiding philosophy. “My life is like a dumpster,” a second protagonist later observes. “Garbage keeps piling up.” Another character’s final words, spoken seconds before he places a gun beneath his own chin and pulls the trigger, are “The world is just disgusting.” Nothing that writer-director Hu Bo orchestrates around these various depressives over the course of An Elephant’s mammoth running time contradicts their despondent feelings, which only makes the film’s tragic denouement even sadder: In October of 2017, not long after he completed his initial cut (and reportedly feuded with producers who wanted to trim two hours), Hu committed suicide. Knowing that, it’s almost impossible not to interpret his debut and final feature as an elaborate note addressed to the entire world, explaining his decision to depart.

Still, the respectful thing to do, it seems, is to treat An Elephant Sitting Still like any other film, imagining how it would look were Hu already hard at work on his next project. A lot depends on just how much sustained misery one likes to endure. Nobody on screen gets anything but bad news at any point, ever. If there’s an adorable little dog—its owner’s only friend—it will be killed (out of frame, thankfully) by a much bigger dog. If someone goes to borrow money from his grandmother, he will enter the house to find her corpse lying on the bed (and will take it in stride, because of course she’s dead—the world is a wasteland). By the end of the first hour, the aforementioned high school student (Peng Yuchang) has accidentally shoved someone down a flight of stairs, landing him in intensive care; the accident victim’s older brother (Zhang Yu) has provoked his best friend into suicide by sleeping with the friend’s wife; and an elderly man (Liu Congxi) has been informed by his son that he needs to take up residence in what we later see, or at least fervently hope, is China’s dreariest nursing home. There’s also a female high school student (Wang Yuwen) who’s become involved with the vice-principal, and discovers later on that a video showing them together has been uploaded onto the internet and is being posted on various chat groups.

That’s pretty much the full extent of An Elephant Sitting Still’s narrative, though it takes a while for the glancing connections shared by these four characters to become clear. All the same, cutting the film down to a normal length would only have harmed it. Like various other filmmakers, from Jacques Rivette to Lav Diaz, Hu employs duration for its own sake, forcing the viewer to grapple with the weight of time itself; shortening such a work often paradoxically makes it feel even longer. (That’s why Kenneth Lonergan spent years struggling to produce a contractually obligated 150-minute version of Margaret, which really needs to sprawl and digress and deliberately ignore crucial elements.) Trouble is, Hu only has a couple of formal moves, which he just repeats over and over. A sizable chunk of the movie is spent following the actors around, Dardennes-style, minus the sense of bruising intimacy that the Belgian sibling filmmakers somehow achieve via sticking tight to the back of someone’s head. Otherwise, most shots split the frame vertically, juxtaposing one or two faces in closeup with some other figure(s) seen at a distance and out of focus. It’s a striking effect that steadily loses impact over the course of four hours as Hu keeps returning to it.

That’s likewise true of every character’s utter exhaustion with the state of being alive. The film’s odd title refers to a circus in another city, which reportedly boasts, as one of its main attractions, an elephant that just sits there, oblivious to everything around it. Such blithe indifference represents Shangri-La to these folks, all of whom eventually express and/or act on the desire to go see the elephant. But it’s hard to become emotionally invested in someone whose impossible dream is to no longer care, and the sense of yearning that might counterbalance all the hopelessness never truly materializes. Hu definitely had talent—the sequence in which the husband discovers his best friend with his wife is a horrifically nondescript tour de force, creating tension from implied context that suddenly fills a void (it hadn’t been clear who any of these people are in relation to each other), and startlingly devoid of either words or action until it’s abruptly too late. Ultimately, the most demoralizing thing about this ultra-bleak ordeal is the knowledge that a potentially major filmmaker will never realize that potential.