Trainspotting’s soundtrack was a gateway for musical addictions to come

In Soundtracks Of Our Lives, The A.V. Club looks at the dying art of the movie companion album, those “various artists” compilations made to complement films on screen but that often end up taking on lives of their own.

Trainspotting made me want to do drugs. This probably wasn’t the film’s intention. In fact, you could say that Trainspotting goes to great lengths to argue that drugs are a pretty bad idea, actually, destroying relationships, forcing you into increasingly desperate acts of deceit and criminality, and leading inexorably toward death and disease—or worse, sheet-twisting withdrawal. And yet, no amount of watching Ewan McGregor’s Renton scream and sweat could have deterred me from thinking that Trainspotting made the drug lifestyle look really exciting, a rejoinder to “Choose Life” conformity wrapped up in the wry, sexy nihilism of “heroin chic.” These weren’t the lifeless, strung-out zombies of D.A.R.E. public service announcements. They were sexy people in sharp suits who knew a lot about Sean Connery movies, and they got high and went out clubbing every single night.

They also—and this is crucial—listened to really cool music. And thankfully, this was Trainspotting’s most lasting effect on impressionable youth like myself: Its soundtrack made me want to be cool, in ways wholly different than I’d even considered. By the time it was released in 1996, I, along with the rest of the kids in America, had already been through several different iterations of “cool.” But if I had to sum up the overarching principle of what I considered to be cool music back then, it would be “people bumming out over guitars.” Certainly, there were shades within that. I liked anger, ennui, ironic jadedness, heartsick romantic pining, and suicidal depression equally. Still, I was largely suspicious of anything that wasn’t built on a bedrock of distortion and bad feelings—and I certainly didn’t think much of electronic music, ’80s dance-pop, or anything that didn’t properly capture my adolescent angst, then funnel it right back to me in a self-sustaining loop.

Trainspotting changed all that. While disenfranchisement, laziness, and heroin had also been the bedrocks of grunge, there they were all tied up in despair: Alice In Chains’ Layne Staley seething about wanting you to scrape his brains off the wall; Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain actually going through with it. Trainspotting returned disaffection to its punk roots, oriented around the film’s guiding star, Iggy Pop, then threw in a dash of the happy hedonism of new wave, Britpop, and rave music. Trainspotting gave the act of throwing your life away for fleeting pleasure an appropriately ecstatic soundtrack, one that was every bit the back-alley rush its story demanded. On screen, the songs—assembled by director Danny Boyle, producer Andrew MacDonald, and former EMI A&R rep Tristram Penna—were all expertly matched to images that pulsed, rolled, and moved with Boyle’s flashy camera sweeps. And that euphoria continued off screen with a compilation album that quickly became an indispensable part of any 1990s musical education, offering the first tastes of sundry genre addictions to come.

Boyle’s team was already given plenty of guidance there by Irvine Welsh’s novel, whose savvy junkies drop regular reference to bands like The Smiths, The Fall, and Simple Minds—sometimes as the only recognizably English words in Welsh’s impenetrable lowland dialect. Like any outsider with big dreams, they also love David Bowie with the same passion as their author. “If you were a young working-class man in Britain, Bowie basically set you free in terms of his aesthetics and his projected sexuality,” Welsh said in a 2016 interview. “I don’t think I’d be a writer if it hadn’t been for that kind of influence and the people he turned me on to—Lou Reed and Iggy Pop and all the soul stuff.” So Boyle, himself a devout Bowie fan, naturally attempted to secure some of his tracks for the film. In another interview, in fact, Penna would later characterize Boyle as “desperate” to do so. But Bowie, the Goblin King of Saying No To Stuff, turned him down. Still, much as he did for Welsh, Bowie became a sort of spiritual and musical fulcrum for Trainspotting in helping it figure out its sound—beginning with the obvious choice of hitting up Bowie’s favorite collaborators.

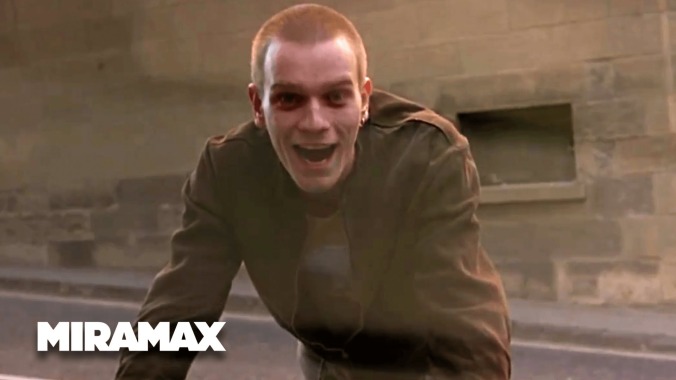

As Penna later recalled to Dazed, it was he who suggested Iggy Pop’s Bowie-produced “Lust For Life” for Trainspotting’s opening, heart-and-sneaker-pounding chase sequence. “‘Lust For Life’ had always been a huge club hit since the Batcave days, so I knew it would get the adrenaline rushing if used in the opening,” Penna said. He was right: McGregor and Ewen Bremner’s feet slapping the pavement in time to Hunt Sales’ immortal drumbeat gives Trainspotting the kinetic kick that sets the tone for everything to follow, the kind of alchemical marriage of music and movie motion that’s often imitated but rarely matched.

It’s not clear why Boyle might have needed Penna—or anyone—to point him in Pop’s direction. In the movie as in the book, Pop is revered as an immortal junkie idol worthy of football club-like devotion, even at the risk of your relationships, so it seems like a given his music would have made it in. But there’s no denying that the “Lust For Life” sequence was, as Penna puts it, “transformational,” both for Trainspotting and Pop himself. Bowie’s co-writing and mentorship on Pop’s solo albums The Idiot and Lust For Life had, in Pop’s own words, once “resurrected” the erstwhile Stooges frontman from the depths of aimless addiction. And here, Trainspotting’s use of “Lust For Life” and The Idiot’s synth-zonked, streetlight stumble “Nightclubbing”—not to mention copious dialogue, in which a bunch of good-looking young people talk about him like a god—dug Pop out of the deep hole of blasé, mainstream acceptance.

In fact, just prior to Trainspotting’s release, Pop was doing fine—great, even. He’d scored his first Top 40 hit with the love ballad “Candy,” and he was making guest appearances as a sort of weirdo godfather on albums from the likes of White Zombie and Buckethead. Still, whatever danger he’d once carried was, at that point, based mostly on reputation. Trainspotting reintroduced Pop’s gloriously rebel-scum self to the kids—even if it helped to sand the edges off “Lust For Life,” specifically. More licensing opportunities inevitably came calling, and soon enough “Lust For Life” was being sanitized for the safety of Rugrats movies and Royal Caribbean commercials. Nevertheless, the old, shirtless, swaggering Iggy Pop was back, ready to be worshipped by a new generation of punk and punk-adjacents.

To Penna’s chagrin, a similar thing happened with his other endorsement. Lou Reed’s “Perfect Day”—“a description of a very straightforward affair,” Reed had once characterized it—had long been interpreted as a subtle paean to heroin, Reed singing about his constant companion who turned such quotidian weekend activities as going to the zoo or the movies into something worthy of sentiment and song. Never mind that Reed had already written plenty of times, and pretty damn bluntly, about heroin. The interpretation lingered, becoming crystallized the moment Boyle used the song to narrate a scene of Renton overdosing.

But even more damaging, in Penna’s view, was the song’s association with adult-contemporary radio. After Trainspotting put the Transformer deep cut back into the broader public consciousness in ’96, the very next year, Reed—along with a jaw-dropping ensemble of musicians that included David Bowie, Bono, Elton John, Emmylou Harris, Evan Dando, Tammy Wynette, Tom Jones, and Shane MacGowan, to name a few, plus a bunch of fleeting pop stars—performed “Perfect Day” for a BBC ad, which then spawned a massive hit charity single. Implicit drug subtext aside, “Perfect Day” has since become the kind of safe pop standard that the likes of Susan Boyle can cover. (“I’m really happy about Iggy,” Penna told Dazed. “I will regret putting ‘Perfect Day’ forward to my dying day.”) Still, to a young Alternative National like myself, having it put in front of me was a sadly necessary reintroduction to the prior generation of cool that Reed, Pop, and Bowie represented. Digging backward into their respective discographies would go on to inform so much of my musical taste going forward.

In 1996, Britpop had already made a beery splash on American shores thanks to Oasis, but unless you were one of those kids who immediately got a shag hairdo and started flicking the V in school photos, odds are that the Gallaghers’ big, bright guitar tunes are pretty much where your Britpop investigations ended. I was dimly aware of the British squawk over who was better, Blur or Oasis, but from my limited, MTV-defined purview it seemed like no contest: Blur did that pretty catchy, kinda-irritating song about “Girls & Boys,” as well as the one where the guy from Quadrophenia rattled off a bunch of inscrutable British slang (spurring Beavis & Butt-head to declare confidently, “England sucks”). Oasis, then dominating every alt-radio playlist and dormitory stairwell, was the “second coming of The Beatles.”

Trainspotting didn’t do a lot to upset that perception, frankly. It would take Blur’s self-titled, mostly Britpop-eschewing album until 1997 (and Oasis’ letdown from the same year, Be Here Now) to change American minds—mine included. In the meantime, we had Trainspotting’s “Sing,” an ethereal ballad plucked from 1991’s Leisure that had a lovely, slightly maudlin wash, plus lyrics practically written for its big movie moment (“So what’s the worth / In all of this, this? / If the child in your head / If the child is dead,” Damon Albarn sings as the group of addicts discovers a baby dead from neglect), but little in the way of “Wonderwall”-toppling hooks.

Albarn’s album-closing solo cut, “Closet Romantic,” is similarly on the nose, but far less engaging. Over some tinny, lounge-lizard Muzak, Albarn offers up a few wordless “la-la”s before archly reading off the titles of Sean Connery’s Bond films, a tribute to both the extracurricular obsessions of Jonny Lee Miller’s Sick Boy, as well as to the permission fame grants you to just phone it in sometimes.

I would later come around on Blur in a big way, but back then it seemed like Albarn was just lucky Oasis had turned the movie down—because, in one of the great Oasis stories, Noel Gallagher thought it was literally about trains. In the meantime, Trainspotting actually did far more for Britpop’s lesser-known second tier—most significantly Pulp, whose swinging, council-house horror story “Mile End” was my first taste of the band and Jarvis Cocker’s deliciously mordant vivisections of class and character.

It sure was a good one. “Mile End” has everything great about Pulp condensed into a single song: evocative details (“The fifth-floor landing smells of fish / Not just on Friday, every single other day”); deadpan observations (“Down by the playing fields / Someone sets your car on fire”); and Cocker’s charmingly haughty, above-the-fray whimsy. Pulp soon became not only my favorite Britpop band, but one of my favorite bands, period. Meanwhile, “Mile End” was already my first indicator that some of Pulp’s best material was being hidden away on B-sides. (“The Professional,” “Cocaine Socialism,” and “P.T.A.” would also fall under this category.)

Elastica, too, although by 1996, I was already very into that band. In fact, I maintain that Elastica’s self-titled debut (regardless of how the members of Wire or The Stranglers might feel) is Britpop’s best front-to-back album, and one of the finest of the decade. The soundtrack’s inclusion of the snaking “2:1” was, for me, redundant, yet its presence offered implicit endorsement of everything that surrounded it—even Sleeper, whose slavishly faithful cover of Blondie’s “Atomic” was fine, but not particularly distinctive (not unlike Sleeper itself). Trainspotting offered a window into what an entire other country’s cool kids were into. By the next year, I was deep-diving into the likes of Suede and Supergrass, just in time for the whole Britpop thing to start winding down.

“The world’s changing. Music’s changing. Drugs are changing,” Diane (Kelly Macdonald) tells Renton at the film’s midpoint, and while she’s specifically chiding Renton for clinging to the passé likes of “Ziggy Pop,” she may as well have meant rock ’n’ roll in general, something that was deeply felt that year. In 1996, there was a reductive malaise settling in over the “alternative” scene; shooting heroin and bumming out to guitars was rapidly being replaced by popping ecstasy and dancing to big-beat electronica. Renton experiences this revelation again while watching a rave crowd bumping and rubbing to Ice MC’s Eurodance hit “Think About The Way,” a movie moment that captures the similar cultural awakening “electronica” was about to have. Much of that could be credited directly to Trainspotting. I certainly do.

“Think About The Way” didn’t make the official soundtrack, nor did the film’s other big club-thumper, Heaven 17’s “Temptation,” although it turned up on the leftovers-and-spiritual-cousins Volume 2, released the next year. But New Order’s own “Temptation,” did, and it, too, spurred my own Renton-like, seismic personal awakening. To younger, idiot me, there was just something so empty about ’80s dance pop; I thought bands like New Order made neo-disco pablum for Bright Lights, Big City yuppies to blow rails to. But Trainspotting brilliantly turns “Temptation” into something honest and pure; when Diane sings its lovelorn refrain to Renton a cappella, there’s nothing artificial there. I fell in love with “Temptation,” along with the rest of New Order’s catalogue, as a precursor to the rediscovery of ’80s new wave and post-punk that would soon overtake me and so many of my friends.

Overall, Trainspotting reserves five of its 14 tracks for synthesizer music, running the gamut of its forms. Brian Eno’s meditative “Deep Blue Day” became another Bowie-adjacent replacement after Bowie, perhaps understandably, didn’t want Boyle’s preferred choice of “Golden Years” scoring Renton’s swan dive into a shit-smeared Scottish toilet. (Bowie eventually changed his mind, sort of: “Golden Years” would also turn up on Trainspotting Vol. 2.) The substitute “Deep Blue Day,” from Apollo: Atmospheres And Soundtracks, was originally composed for a documentary on the Apollo space missions, intended to conjure the Earth’s ineffable majesty through Eno’s synth-pad swells and Daniel Lanois’ wistful Western guitar bends. Instead, it became most famously juxtaposed with Ewan McGregor chasing suppositories through the sewer. It’s one of the film’s most oddly beautiful sequences, and its prime, track-two placement on the album gave many—myself included—their first taste of ambient music, a genre that now forms 70 percent of my listening habits.

There’s also Primal Scream’s nearly 11-minute instrumental “Trainspotting”—a collaboration with DJ Andrew Weatherall that couldn’t have been further afield from 1994’s Rolling Stones-ripping Give Out But Don’t Give Up, but which hinted at the direction the band was about to take on 1997’s revitalizing Vanishing Point. Years later, in an interview with Spin, Primal Scream frontman Bobby Gillespie said they’d personally pitched doing something directly to author Irvine Welsh, after learning that the posh likes of Blur and Pulp had been included: “We’re the junkie fucking band! And we’re working class!” Gillespie said. And although there’s little hint of that hooligan grit in the trip-hop-leaning “Trainspotting,” the song does conjure a sort of vial-strewn-sidewalk seediness—and romanticization of same—with its dubby rhythms and flecks of spy guitar underscoring the distant, persistent ring of a mobile phone.

But far more important than those two cuts—particularly to anyone whose idea of “electronic music” was limited to oonce-oonce abstractions that people in enormous, shiny pants flailed to—were the three tracks from artists working in the subtler subgenre known as “progressive house.” The term was first applied to the duo Leftfield, in fact, whose “A Final Hit” here is archetypal: Ostensibly dance music, it’s far better suited for sitting perfectly still, caught up in the creeping paranoia of subliminal bass rumbles and watery synth echoes. (Boyle loved Leftfield, using them in both his debut, Shallow Grave, and 2000’s The Beach.) Producer and DJ John Digweed was also on the vanguard of the progressive house movement, and Trainspotting’s use of “For What You Dream Of,” recorded under his Bedrock alias with Nick Muir, was the first mainstream introduction a lot of listeners had to his spin on the sound, a blend of trance textures, futuristic burble, and disco euphoria that’s near-psychotropic. It sounds a bit dated now, but for warehouse-averse wallflowers like me, it was an entry point to an entire, intimidating world.

Still, practically every breakout “electronica” act that followed Trainspotting’s success can be traced to its signature song. By 1996, Underworld’s Karl Hyde and Rick Smith had been making music together for seven years, first dabbling in classic synth-pop under the name Freur before evolving into the techno fusions of 1994’s groundbreaking dubnobasswithmyheadman. The elements of that album—which added warmth, playfulness, and, most importantly, a human voice to techno’s rigidity—were all present on “Born Slippy .NUXX,” a song the duo had originally tossed out as a B-side remix.

It would have stayed there, too, had Boyle not convinced Hyde and Smith that he didn’t want to use it as some kind of druggie anthem. Having the complete opposite reaction from Primal Scream, Hyde told Spin they were “horrified” by Boyle’s request, “because we’d never seen our music as having anything to do with drug taking.” It was only after Boyle showed them some of the darker scenes that the group relented. The result was one of the most perfect marriages of music and film since, well, Trainspotting and “Lust For Life.” The movie closes with “Born Slippy .NUXX,” bookending its jolt of an opening by having the song’s 4/4 propulsion similarly match Renton’s march into his future, all while those epically reverberating chords swirl together with Hyde’s delirious, vertiginous narration of a drunken night out spiraling into blackout abyss. It’s grimy and grand, anxious and euphoric, all at once. Boyle couldn’t have picked a better, more appropriate song.

“Born Slippy” was a cross-genre monster. It catapulted Underworld to international stardom (a burden the band says it’s struggled with ever since), and its success exposed the British dance scene to a massive audience—one that would no longer look at electronic music as niche or novelty, or require some rock ’n’ roll element (like Noel Gallagher’s guest spot on The Chemical Brothers’ “Setting Sun” from that year) to justify it. “Trainspotting and ‘Born Slippy,’ they carved their own little space out in that time, I think,” Hyde told Spin in 2016. “They’re synonymous now. And in a way, I think it’s like that culture’s Woodstock.”

Hyde’s probably overstating things (even Woodstock wasn’t really anyone’s “Woodstock”). But he’s right that “Born Slippy” and Trainspotting both heralded an epochal shift. Increasingly, radio and MTV started working electronic music into its alternative and pop rotations; by the summer of ’97, Lollapalooza’s main stage was nearly all electronic acts who’d emerged from Underworld’s tent: The Prodigy, Orbital, The Orb, Tricky. Half of the kids there probably had a copy of the Trainspotting soundtrack in their CD wallets. (To Hyde’s chagrin, a lot of them were also probably doing drugs.) And so many of them were, only two years before, people like me who’d warily regarded music that wasn’t made using only guitars and unhappiness.

Ultimately, a lot of them found “electronica” to be just another fleeting addiction. You can only chase the highs of something like “Born Slippy” for so long, after all, and the glut of increasingly slick electronic music that followed, some of it more noticeably stepped-on than others—Fatboy Slim, The Crystal Method, Moby, Ray Of Light-era Madonna, etc.—eventually left the listener numb to its effects. Inevitably, “electronica” splintered back into its various niches, allowing its various forms to become even more experimental and vital. But for many, the Trainspotting soundtrack had provided a gateway to appreciating and understanding it, placing it along a lineage that stretched from Bowie through Britpop to big beat. It established a historical continuum of cool that you wanted to investigate, to be a part of, to get addicted to. Even today, I’d wager it still has the power to get you hooked.