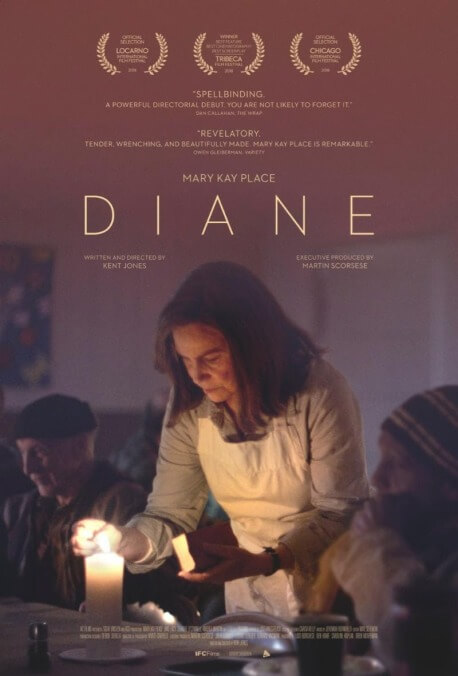

A standout at last year’s Tribeca Film Festival (where it won Best Narrative, Best Cinematography, and Best Screenplay), Diane is the debut fiction feature of Kent Jones, a storied film critic and the current director of the New York Film Festival. (He previously made the documentary Hitchcock/Truffaut.) Understandably, then, the movie—on which no less than Martin Scorsese serves as executive producer—demonstrates a clear grasp of cinematic form and grammar. Jones’ pendular editing patterns move the viewer between key locations (Diane’s home, her son’s apartment, Donna’s cancer ward), with countless interpolated shots of Place driving along the slick highways and snowy side streets of the Bay State. The film’s standout scenes—Diane’s visits to Donna, a casual kitchen-table hangout with elderly relatives and friends—have an easy, naturalistic tenor indicative of the shared histories and cumulative experience of those involved. But Jones also imbues the film with a kind of pensive unreality, using dreamy, molasses-slow crossfades to lull the viewer into an almost trancelike state.

Much less successful are Diane’s awkward stabs at actual drama. The programmatic mother-son relationship between Diane and Brian, which should be the film’s wrenching core, pales in comparison to that of Josh Mond’s James White, an absorbing, finely shaded character study that observed a similar dynamic from the opposite point of view. Lacy in particular struggles to make his limited screen time count, rarely distinguishing his role beyond stereotypical drug-addict volatility and obvious actorly tics. When Brian unexpectedly cleans up late in the going and becomes a born-again Christian, the resulting shift in dynamic—he ends up accosting her to reform herself by joining his church—offers a glimmer of potential. Even this narrative line, though, eventually leads to a climactic monologue that registers mainly as indie cliché. (Still, this is preferable to an earlier scene of Diane, at her lowest point in the story, getting drunk alone at a bar and dancing her cares away.)

In all this, there remains a purposeful if haphazardly realized design. As Diane’s relatives and friends continue to fall away with the passage of time, Jones intensifies the film’s discombobulating rhythms, taking Diane from hard-edged physicality to a more interiorized, subtly dreamlike haze. (No points for recognizing the head-smacking irony of the lead character’s name, though at least her family name isn’t “Young.”) The veracity of specific scenes (including the ones with Brian) thus become tinged with the possibility of wish-fulfillment projection. Compared to Diane’s rather staid first half, this ambitious formalist turn is welcome. But fittingly, perhaps, for a film so fixated with death, it’s too little, too late.