If the name Mark Hofmann or the term “the Salamander letter” immediately ring bells, then you have a road map for the twists and turns Murder Among The Mormons takes. Greater context is provided for even those who followed along with (or, decades later, just ended up down a digital rabbit hole one night) the years-long coverage of the series of mail bombings that took place in 1985. But the show is a solid primer for those unversed in the late-20th-century collision between the Church Of Jesus Christ Of The Latter-day Saints (also known as the Mormon Church or LDS Church) and one impossibly lucky document collector. Hess and Measom don’t editorialize or otherwise insert themselves into the production, beyond posing a question that shakes one of the more ostentatious interviewees late in the series. Aside from one giddily quirky mid-series sequence, they also don’t bring much character to the format, which is surprising, given the directors’ previous work.

Maybe Hess and Measom thought it best to let the story—and several of those affected by it—speak for itself. They certainly don’t seem to want to mythologize Hofmann, who killed two people on October 15, 1985, to cover up decades of increasingly ambitious fraud. Murder Among The Mormons is mostly sober in its approach to Hofmann’s crimes, opening with a montage of news reports on the mail-bomb killings of Steve Christensen, a document collector and bishop in the Mormon Church, and Kathy Sheets, the wife of Christensen’s former boss, Gary. The people of Salt Lake City, a Mormon stronghold, were all on edge, and their fears only grew when a third bomb exploded in Hofmann’s car on October 16. Early on, police theorized that a disgruntled former investor went after Christensen and Sheets. But the focus of the investigation quickly turned to Hofmann, whose Toyota MR2 was filled with intriguing mid-19th-century documents at the time of his “attack.”

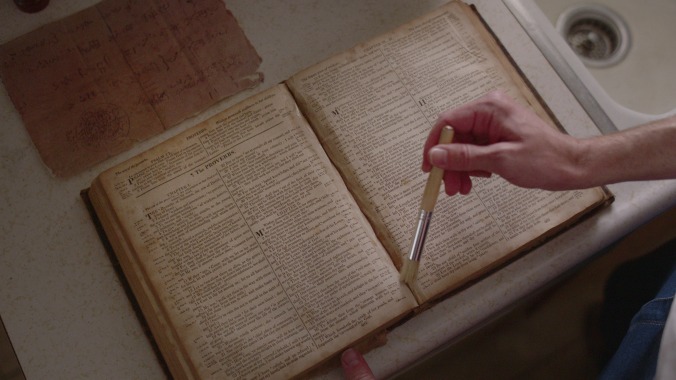

The rest of the first episode plays out like the opening gambit of many a true-crime series, presenting a narrative only to introduce a few complicating factors. Hofmann was a victim, until he wasn’t. That change in direction comes before the first 30 minutes are up, but Hess and Measom take time to lay important groundwork, including providing a closer look at the competitive world of rare document dealers and touching on some of the founding tenets of Mormonism itself. Document collectors and historians describe the element of “treasure hunting” that became a more general preoccupation with discovery within the LDS Church. In the ’70s and early ’80s, every discovery that Hofmann and his contemporaries—including docuseries interviewees Brent Metcalfe, Shannon Flynn, Alvin Rust, and Brent Ashworth—was met with cautious excitement. The LDS Church was keen to acquire any item that would fortify the foundation of their institution. The Church was also, according to many of these dealers and some congregants, just as eager to obtain any documents that could undermine the organization.

That realization shades some of the decisions made early on, but it’s not meant to obfuscate the truth of Hofmann’s crimes, nor disperse any of the blame. (Hess and Measom were both raised in the Mormon Church, and are very thoughtful in providing this background info.) The LDS Church’s efforts to flesh out its own history occasionally look like attempts to shape that very history, by locking away contradictory letters in archives and even denying their existence. Hofmann didn’t just exploit that inner conflict—he reveled in the bait-and-switch of having unearthed some rare correspondence, only to have it raise doubt about the LDS Church dogma. In interviews conducted after his conviction, Hofmann described the thrill of deceiving others: “Fooling people gave me a sense of power and superiority.” This college dropout managed to trick reputable experts and even the FBI. But it’s clear that, as a lapsed Mormon turned atheist, he took special pleasure in fooling the LDS Church. An interesting parallel is drawn between Hofmann and Joseph Smith, who both went looking for treasure as young men, and who each had an outsize impact on the Mormons.

The final hour of Murder Among The Mormons includes archived footage of Christensen’s widow, Terri, and contemporary interviews with Hofmann’s living victims, but is designed to get at what motivated this virtuoso of fraud. Along with decades-old interviews with Hofmann himself, these talking heads form a chilling portrait of a consummate forger—even government officials allude to the “sophistication” of his schemes—and an opportunist. At one point, Hofmann admits the second bomb didn’t “have” to go off, but that he didn’t really care enough to make it simply a dud. There are some gaps in the storytelling, especially when it comes to Hofmann’s sentencing—after years of convening in a “war room” to expose the man, gung-ho prosecutor Gerry D’Elia and detective Michael George have nothing to say (or just weren’t asked) about the plea bargain that covered two murders and just a handful of other charges. And, despite raising important questions about authentication and the rare-collectors world, Hess and Measom leave certain recent events undiscussed. But what Murder Among The Mormons does establish in its truncated format is that Hofmann was consumed by deception, both what he believed existed in the Mormon religion, and the many deceits he felt justified in deploying. The moral of this story is as straightforward as any parable: If something seems too good to be true, it probably is.

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)