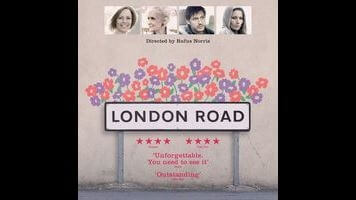

True crime gets the musical treatment in the radical, thrilling London Road

Verbatim theater, in which every word the actors speak derives from recordings of real-life interview subjects, is even trickier to adapt for the screen than ordinary theater can be. In order for the form to offer something distinct from the interviews themselves, a certain degree of cognitive dissonance is required. The stage, being a blatantly artificial construct, provides this more or less automatically. Movies, which occupy a wider continuum from the concrete to the abstract, need to work a bit harder.

That said, it can be done, and even done magnificently. The Arbor, for example—which landed on our list of 2011’s best films—achieved an uncanny effect by having the cast lip-sync to the original interviews. And London Road, the screen adaptation of an acclaimed British play inspired by serial murders in Ipswich (a huge media story in England circa 2006-07, though it didn’t travel far), required no bells or whistles at all. Why not? Because, improbably, it’s a verbatim musical (book and lyrics by Alecky Blythe; music and lyrics by Adam Cork), and nothing counteracts extreme verisimilitude like people suddenly breaking into song.

Given the lurid subject matter, one might expect a mystery or a thriller, but London Road is neither—the murders aren’t shown, and the killer’s identity is never in question. Instead, it views the crimes entirely through the reactions of the area’s residents, who are alternately terrified, appalled, titillated, blasé, and defensive. All of the victims were prostitutes, and one woman, Julie (Olivia Colman), expresses a guilty feeling of gratitude toward the killer for ridding her neighborhood of what she considers an undesirable element. Tom Hardy makes a slightly distracting cameo as a cab driver who feels obliged to tell passengers that his rabid interest in serial killers doesn’t make him a serial killer. Most of the other actors are carried over from the National Theatre production, and they function as a tight ensemble, creating an indelible portrait of one very specific part of the country (about 60 miles northeast of London, in Suffolk).

As pop sociology, London Road doesn’t delve terribly deep, repeating the same simple observations (principally: people are self-interested) over and over. As a nearly avant-garde musical, however, it’s a constant grin-conjuring marvel. Blythe and Cork incorporate everyday vocal imprecision—ums and uhs, stuttering repetition, even nervous laughter—into the very structure of the songs, creating offbeat cadences and weaving them into contrapuntal harmonies. Phrases are initially spoken, then sung by one character, then sung by the whole ensemble, with everyone retaining the original speaker’s various idiosyncrasies. If one person’s role in the interview mostly involved appending a “yeah” to everything her friend said, the resulting song will employ all the “yeah”s as a rhythmic device. Even reporters covering the crime and the subsequent trial have their on-air patter transformed into unusual yet catchy melodies. It’s disconcerting at first, but the strangeness magnifies casual remarks that might otherwise seem banal.

Director Rufus Norris deserves credit, too, for making a real movie, rather than merely recreating his stage triumph in front of a camera. While his background is almost entirely in theater, his first feature, Broken (2012), demonstrated so much formal confidence that viewers unaware that it’s adapted from a novel would be hard-pressed to guess that fact. London Road’s transition seems to have made him a bit more self-conscious, as he arguably works a little too hard at visual variety here—angles are sometimes needlessly canted à la Tom Hooper (Les Misérables), and the cutting can seem frantic à la Rob Marshall (Chicago). On the whole, though, Norris has reconceived the play with panache, especially when it comes to laying out the geography of London Road itself (though the film was actually shot in Bexley, an area of London). It takes a while to realize that, despite the familiar presence of Colman and (briefly) Hardy, the movie has no protagonist and is equally interested in everyone, including the area’s surviving sex workers. It’s a valuable record of a community in crisis, rendered vivid and unforgettable by literally making it sing.