The last three elements are easy to convey, and they’re clearly up there on screen. Problem is, the genius part is much more difficult to bring across, since it was specifically confined to the written word. In the end, director Jay Roach (Meet The Parents, Meet The Fockers) and screenwriter John McNamara have to settle for characters periodically announcing that Trumbo is brilliant, which produces an uncomfortable, unintended tension throughout the film. Should viewers judge based on what they can see, or on what’s constantly being dictated to them? In a film that’s so openly about shallow agendas and self-serving manipulation of public perception, that becomes a particularly troublesome question.

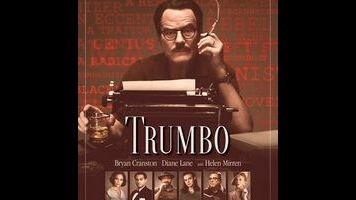

Credit Trumbo with not turning Trumbo himself into a paper angel to make the question simpler. As played by Breaking Bad’s Bryan Cranston, he’s an irascible old coot who speaks largely in polemics and one-liners, and strides boldly through life, armored by his principles and his ego. The film isn’t subtle about his idealistic stance on income equality and workers’ rights: The scene where he explains his politics to his pre-teen daughter feels like a communism commercial conceived by a team that normally handles ladies’ hygiene products. (He’s leading her on a pony in a sun-dappled yard; she asks, with grave concern but also deep love, “Dad? Are you… a communist?”) But Trumbo also isn’t subtle about his temper, or his faults and failings.

The film opens in 1943, with title cards that attempt to contextualize communism in the 1940s for generations that grew up with the word as a shadowy bogeyman. In the film’s perspective, Trumbo wasn’t a barn-burner or a Russian sympathizer, he simply believed that the workers who made films had as much rights to the profits as the financiers that threw money at them. But as U.S. Congressman J. Parnell Thomas (James DuMont) and the House Un-American Activities Committee fire up their anti-communist witch hunt in Washington, with the staunch support of gossip columnist Hedda Hopper (Helen Mirren), Trumbo and his friends are called on to admit their Communist Party connections and out all the other radicals and subversives they’ve allowed under their roofs. Instead, Trumbo and others—the “Hollywood Ten”—defy Congress, go to jail, and wind up blacklisted. From there, Trumbo struggles to make a living and support his family in a Hollywood economy where everyone wants what he’s selling, but few can afford the associated costs of Hopper’s wrath and Washington’s attentions.

In spite of Cranston’s bombastic performance and all the Oscar Wilde-esque snarky one-liners McNamara (and history) hand him, Trumbo himself winds up as one of the least interesting parts of Trumbo. He’s a colorful figure, but the film is overstuffed with more colorful elements. Mirren plays Hopper as a slightly more internal Cruella De Vil, blackmailing bigwigs and shepherding stars around with a sweet smile and an acid tongue. Plenty of the other figures are more recognizable than Trumbo—like David James Elliott as John Wayne, seen here as a huge man with a slow drawl and a bully’s furrowed-forehead bafflement when cleverer people challenge his simplistic beliefs. Or the Hobbit movies’ Dean O’Gorman, playing Kirk Douglas with a tight smirk and an expansive drawl. A Serious Man’s Michael Stuhlbarg plays Edward G. Robinson with a gentle affect that’s the opposite of his hard-edged gangster roles. And Christian Berkel steals so many scenes as Otto Preminger that he recalls Corey Stoll shutting down Woody Allen’s Midnight In Paris whenever he turns up as Ernest Hemingway. Even lesser-known figures from the HUAC years (Ian McLellan Hunter, Arlen Hird) become distractingly pleasant highlights, given that they’re played by Alan Tudyk and Louis CK, respectively.

All the bright lights and big stars seem meant to serve as background to the story of Trumbo’s blacklist years, to give a sense of when and where he worked. But they wind up producing a patchwork film that dives into whatever character is in focus at any given moment. Sometimes Trumbo is a weighty prestige picture about a principled man fighting for what he believes. Sometimes it’s a comedy about a conniver, scheming to undermine a corrupt system with the help of larger-than-life funnyman figures like John Goodman and Stephen Root as upbeat schlockmeisters Frank and Hymie King. Sometimes it’s a grim drama, as Trumbo clashes with his weary family at home, particularly his teenage daughter (Elle Fanning), who’s increasingly devoted to integration and the civil rights movement—her own social-justice cause, rather than her father’s. At times, the shifts between melodrama and heist caper recall Argo, but Trumbo’s stakes are lower, its goals are more diffuse, and its comic elements aren’t as separated.

And the constantly shifting focus and peppy pacing don’t leave Trumbo himself much time to develop as anything but a series of blustery speeches, grim confrontations, and pat summations. Most frustratingly, the film never even attempts to communicate what was unique or effective about his writing. It settles for noting the big titles under his belt, and hoping the audience has seen those films, or at least knows them by reputation. Trumbo is the eye at the center of a big, complicated historical storm, but it’s hard to get a sense for either element, past the broadest strokes and the biggest names. Ultimately, the film closes on a series of real-life photos that seem intended as evidence of tiny things Trumbo got right—“Look, Dalton Trumbo really did work from a bathtub! Hedda Hopper really did wear garish, elaborate hats!” But as sharp as the details are, the bigger picture is blurred. Plenty of characters explain to the audience how to feel about Dalton Trumbo and what he accomplished. The movie itself never seems as certain.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.