It’s time for actors to stop writing memoirs.

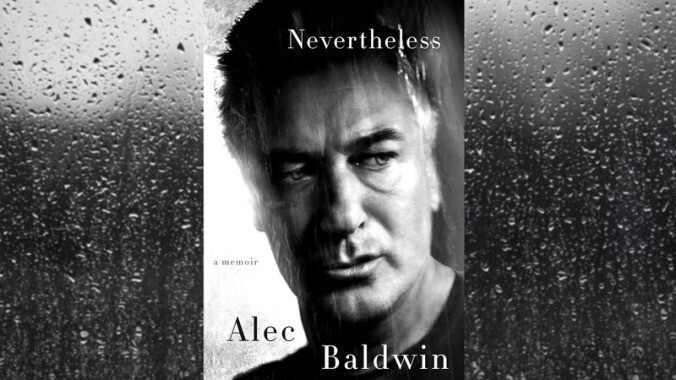

His thin and rambling book opens, “I’m not actually writing this book to discuss my work, my opinions, or my life. I’m not writing it to explain some of the painful situations I’ve either landed in or thrown myself into. I’m writing it because I was paid to write it.” It ends, “I have neither the time nor the talent to write a book.” Perhaps he shouldn’t have.

Nevertheless follows a familiar path for this genre: a brief sketch of the author’s childhood and family (though brothers Stephen and Billy barely figure; surely there’s something to say about the impact show business has on sibling dynamics?), the first steps into creativity and performing, early setbacks and triumphs, and eventual success. On this last point, if nothing else, Baldwin has a leg up on other celebrity cash-ins, as his career has been both long and varied, with periods both in and out of favor.

The problem is, Baldwin’s as good as his word: he doesn’t discuss his work, not really. The seven years he spent on 30 Rock get less than six pages, with no inside scoop or anecdotes. Noteworthy projects like Glengarry Glen Ross or The Cooler, for which he was nominated for an Oscar, get even less—sometimes as little as a paragraph (at one point he blasts through 19 titles, everything from The Departed to The Cat In The Hat, in list form). The book was written recently enough that his guest stints as Donald Trump on SNL are mentioned, but without any insight into how he plays the role, how he feels about it, or about the bizarre place he’s in, where a sitting president routinely blasts his impression.

Baldwin’s Trump-ian qualities of self-regard and remembering slights are on full display in this remarkably petty and oblivious book. The projects he discusses in more depth, like The Hunt For Red October or The Edge, are viewed through the prism of the slights he felt he was receiving from producers or studios. When building to a moment of triumph—New York Times theater critic Frank Rich’s rave review of his Streetcar Named Desire performance—Baldwin turns instead to his nemesis Ben Brantley (Rich’s replacement), who “seems to serve a function for the Times similar to Page Six in the Post, insofar as his writing is random, uninformed snark.” We never actually hear Rich’s take; Brantley’s negative review (decades later, about a different play) is what Baldwin evidently remembers. Later, Baldwin implies that a campaign appearance he made for Ted Kennedy tilted the scales, helping him beat Mitt Romney in a Senate race. (Kennedy got almost 60 percent of the vote.)

It’s understandable that Baldwin would want to use his memoir to reassert his point of view on various controversies, but the random snark, so to speak, about the media, Hollywood types, politicians, and so forth is beyond tedious, especially since there’s no real structure or finesse to the prose itself. Baldwin writes with no eye toward pacing, building an argument, or even consistency. Following the notoriously vicious voicemail he left his daughter Ireland, he writes, “In all honesty, my relationship with my daughter was permanently harmed by that episode.” Admirably forthright, except four sentences later he claims, “My relationship with Ireland has healed.” Is this nitpicking? Probably. Is this book lazily written regardless? Absolutely.

When Baldwin tries something fancier, like recounting a bad drug experience in a stream-of-consciousness style, it’s so confusingly depicted that you can’t tell what’s meant to be paranoia, hallucination, or reality, which deadens the sense of guilt he feels about it. It’s likely no celebrity will breach the padding nadir of Poehler’s Yes Please, which included blank pages for readers to recount the story of their birth, but Baldwin does his best with a multi-page A-Z list of actors he likes. Ultimately, no Baldwin fan will find anything of interest in these pages, while those who hate him will find nothing but new ammunition. Trump will be thrilled: Nevertheless is Art Of The Deal-level disposable.

Purchase Nevertheless

here, which helps support The A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.