Turns out it’s the perfect time to watch Wild West women take aim at marauding men in Godless

Scripted TV usually doesn’t have the luxury of timeliness. Late-night talk shows, sure, maybe the occasional animated satire. But the relevancy of a series like The Handmaid’s Tale is the result of reading the wind, sensing that something, just something, in the air has folks prepped for a cautionary tale about a misogynist dystopia masterminded by scripture-twisting maniacs.

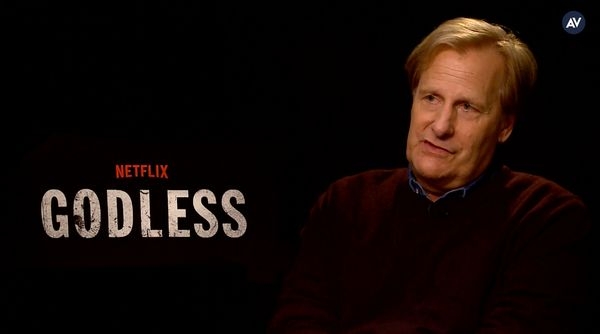

Logan screenwriter Scott Frank wasn’t seeking to make the ideal Western for the current cultural moment when he sat down to write Godless—for one thing, he started work on the script that spawned the Netflix limited series some 15 years ago. And yet, here comes Godless, riding into town on the back of a tale about the backwater of La Belle, New Mexico, where a mining accident killed most of the menfolk, leaving the women to run things. Meanwhile, multiple bands of vulturous men circle La Belle, chief among them Frank Griffin (Jeff Daniels), a silver-tongued outlaw with a complicated sense of morality, a history of posing as a preacher, and a score to settle with his gang’s horse-whispering surrogate son, Roy Goode (Jack O’Connell). At a time when each new day brings another set of stories about powerful men abusing their positions to prey on women, there’s a tremendous amount of catharsis to be found in the image of Michelle Dockery and Merritt Wever, standing shoulder to shoulder, cocking rifles in preparation to pump a few slugs into a one-armed, bloviating Jeff Daniels.

Godless doesn’t reinvent the wagon wheel, but it gets a few good spins out of trusty Western standbys in its too-long seven-hour run. The limited series struggles to recover from an early peak; in the final 20 minutes of the premiere episode, all the pieces for an epic oater fall into place: The massacre that tears Griffin and Goode apart, the tragic circumstances that mark La Belle as the place where they’ll inevitably swap bullets, majestic footage of men in wide-brimmed hats riding their steeds across shallow waters. Godless is handsomely made stuff, stocked with sweeping frontier vistas and stirring performances from a wealth of TV all-stars. (In addition to Dockery, Daniels, and Wever, there’s Scoot McNairy as La Belle’s myopic sheriff, Thomas Brodie-Sangster as his hotshot deputy, and Sam Waterston as a crusty U.S. Marshal with a heck of a fuzzy horseshoe on his upper lip.) But the strain of expanding Frank’s original screenplay shows through in lumpy middle sections that sometimes feel like obstacles to the climactic pyrotechnics, their runtimes varying wildly: some pushing toward feature length, one coming in shorter than an episode of a network drama (minus commercials).

What Godless’ sense of manifest destiny is supposed to afford is a firmer grasp on its characters, none of whom would be fit to trade “cocksucker”s with Al Swearengen. Wever comes closest in the role of Mary-Agnes—whose reaction to the La Belle mine tragedy is to fill the town’s masculinity gap all by herself—but much of that has to do with the shit-kicking spark she brings to the character. Within the constraints of its seven episodes, Godless operates mainly between the poles of Griffin and Goode, the former the big, colorful baddie with the scenery-chewing monologues, the latter the ironically named ne’er-do-well seeking the absolution his mentor preaches but doesn’t believe in. That’s about as deep as Godless can go, all the while hopping in and out of flashbacks to elaborate on how these people came to live at Western civilization’s edge, widows and orphans surviving alongside the indigenous people of the New Mexico territory and an encampment of former Buffalo Soldiers, two groups whose stories feel less familiar than the others, but are crowded to the edges of the series by the Griffin-Goode conflict. Deadwood fans’ ears will no doubt perk up when that old specter of statehood is broached, the suggestion the Griffin gang and their criminal cohort will soon be supplanted by a more sophisticated variety of bandit, like the mining-company thugs and the Pinkerton who winds up sniffing around La Belle.

The gunfights are captivating, and Scott Frank sure knows how to pepper in the comic relief, but Godless all comes back to La Belle—even if the series is more interested in a rivalry between criminals, and even though many of its most interesting interpersonal scenes take place at the homestead that serves as a refuge for local pariah Alice Fletcher (Dockery). Intentionally or not, period pieces can’t help but reflect the times in which they were made; everything that happens among the women left behind by the mine explosion can’t help but feel more urgent to those of us who live in a world where the Frank Griffins don’t announce themselves with profound pronouncements and the stink of rotting flesh.

The setting is both the strongest articulation of Godless’ primary theme—that these characters must fend for themselves, because no one else will—and a powerful denial of it. The state of affairs in La Belle isn’t ideal, but aspects of its citizens’ lives have changed for the better: For example, they can make a living in a place that isn’t a bordello. (Though, as the sex worker-turned-school marm points out, the madam and her employees were also the wealthiest people in town, so the power dynamics may have been a little more nuanced than that.) La Belle’s main street is a grave that later serves as a fortress, the walls of which provide cover in a blazing shootout to preserve lives and a way of life. It’s strong imagery, but Godless goes one stronger: the bees that plague Griffin in the wilderness, stinging symbols of industriousness, community, and matriarchy. Seems about right.

Reviews by Sean T. Collins will begin running Monday, November 27.