Why on Earth does Twisters keep referencing Frankenstein?

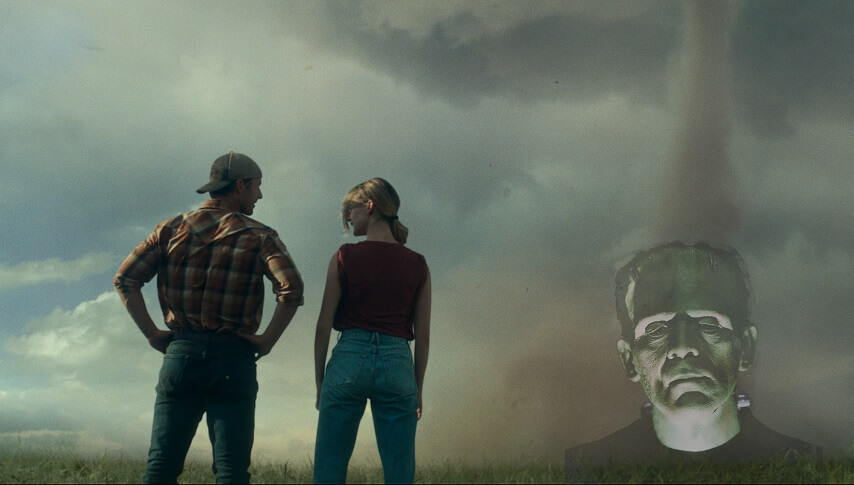

Original image: Glen Powell and Daisy Edgar-Jones in Twisters (Photo: Universal Pictures) Boris Karloff as Frankenstein (Photo: Bettman/Getty)

Stop us if you’ve heard this one: An obsessive scientist, armed with outsider ideas and a spark of divine inspiration, launches an experiment to harness and tame one of the fundamental forces of nature. Despite the science being so right, this effort to tamper in god’s domain goes disastrously wrong, killing the scientist’s companions, and sending them into haunted seclusion. Years later, the scientist is lured back by their deep-seated need to make it right—and prove the world wrong—ignoring conventional wisdom and determining that only their genius can save everyone. Then, the inevitable occurs: The scientist turns out to be right, everybody lives (except some asshole motel customer played by Bill Paxton’s kid) and the scientist gets to share smoldering looks of appreciation with not one, but two, certified Hollywood hunks.

Ah, the classic Frankenstein narrative!

And, look: We wouldn’t normally go after a movie as ideas-light as Lee Isaac Chung’s Twisters—a film so afraid to say anything about anything that, as noted by our colleagues over at Paste, it won’t even whisper the words “climate change” for fear of offending the weather agnostics in the crowd—for failing to pursue a deeper thematic exploration of ideas it briefly toys with re: science and obsession. Except, that is, for the fact that Chung all but dares the viewer to think about this stuff, by setting the final setpiece of his film in an Oklahoma movie house prominently showing James Whale’s 1931 classic Frankenstein. (The film’s final, and biggest, tornado, codenamed “The Monster” by its crew, literally rips the movie’s screen away at the height of the older flick’s most famous scene.) Which forces us to ask, at inceasing levels of irritation the more we think about it: Why the fuck would you put Frankenstein in your movie if you’re not telling some flavor of Frankenstein story?

Frankenstein is, by its most basic, bare-bones, grade school definition, a story about a monster that man brings upon himself. We’re not claiming to be scholars or anything for saying this; literal children can draw that basic inference from a Frankenstein parody they catch in the midst of an episode of Looney Tunes. Man fucks around, man finds out, in form of big green man with bolts in his neck. It is the story of technological hubris coming back to get you in the ass, to the point that you can’t really reference it in another work without making your audience think about those themes. (Or at least make them think that you were thinking about them.) But Twisters, a film in which no one (except those awful, horrible city types, with their big money and clean trucks) ever does anything wrong, is not that film. It’s a movie disinterested in blaming anyone for anything; none of its characters even get mad at the tornadoes. Unless you want to contend that Chung is trying to make a very subtle, subversive point about humanity’s overall and collective impact on climate change—in a movie that otherwise reacts to “subtlety” the way Frankenstein’s old pal Dracula shied away from garlic and crosses, and which is about as subversive as a big plate of barbecue that’s been lovingly shot to radio-play country music—then Twisters is completely disconnected from any of the actual themes of Whale or Mary Shelley’s work, despite the fervency with which it references them.

Somewhat amazingly, Chung has directly addressed this topic, while also not appearing to grasp the fact that Frankenstein has almost nothing to do with the movie he actually made. “I thought of this film in many ways as a monster movie,” he told Variety in a recent interview. (So far, so good. There’s a long history of disaster movies and monster films lending each other thematic weight by borrowing each other’s tropes; last year’s Godzilla Minus One got a ton of mileage out of conflating such larger-than-life forces.)

But then, inexplicably: “Universal has had quite a history of monster films, in which Frankenstein is probably the key. Once I had that in mind, I also thought about the way that tornado is born and formed.” Chung attempts to draw some parallels between the way The Monster apparently picks up speed and energy after it hits an oil refinery, a scene that seems to mostly exist to add some pyro to a film that keeps its big effects shots largely wet and blustery. But also, like, what the fuck? Where’s the connection he drew between his film and Whale’s? The point of Frankenstein is not “We were all minding our own business one day, and then a giant monster came down from the sky for no reason and killed everybody.” You can’t use the world’s most classic story of man creating his own monster to add weight to a story whose entire point is that, “Hey, monsters just happen sometimes, you know? Hope somebody fixes that!” God damn it, now our eye is twitching again.

The wild thing is that it didn’t have to be this weird. There’s a slight implication, in the film’s (pretty good) prologue, that something more complex might be kicking around in the back of the script’s head. After Daisy Edgar-Jones’ Kate releases her Science Stuff into the tornado she and her team are chasing, trying to calm it down, someone notes that the twister almost immediately gains in speed and force. It’s easy to extrapolate, from that moment, a movie in which Kate caused the storm that killed her friends, by tampering with the forces of nature. Like, well… Okay, we can’t actually come up with a simile to fill in there, because “trying to control the weather” is already at the top of The Big List Of Hubris Metaphors. But that would make Twisters a film about, y’know, Frankenstein shit. Hubris. The war between man and god. Science’s reach extending way past its grasp, and getting its hand slapped down in the process.

But Kate is no Dr. Frankenstein, and The Monster is not, uh, The Monster. There’s another Chung quote that actually lays out his whole thinking on this, and it exemplifies why Twisters‘ Frankenstein references feel so weird and hollow. “Daisy was reading this book on Greek mythology in between takes,” Chung notes at one point, discussing filming the movie’s final big action sequence. “I remember looking at the monitor and I just thought, ‘Oh, this is the scene where she really becomes like a Greek god. She’s contending with weather and she takes charge of being a hero.’” And that’s when you realize Chung wasn’t making a monster movie out of his disaster flick: He was making a superhero movie. Kate’s not a tortured scientist, contending with the mistakes of the past; she’s a god-figure who can literally tame storms. (It feels telling, in this reading, that the original Twister was just about getting a really good look at the unstoppable killing might of a full-power tornado without getting smashed to pieces, while Chung’s film is obsessed with slaying them.) They should have had 1978’s Superman showing in the movie theater, instead of Frankenstein; it wouldn’t have been any less on the nose, but it would have been a whole hell of a lot less irritating.