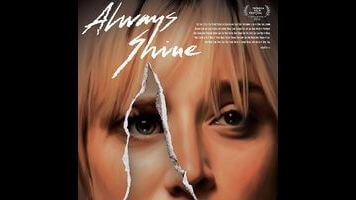

With that simple, superbly jarring juxtaposition, Always Shine—written by Takal’s husband, Lawrence Michael Levine (Wild Canaries)—has already set its thematic wheels in motion. Beth and Anna represent two contrasting modes of moving through a male-dominated world, and their longtime friendship is under a great deal of strain. Beth plays the game, accepting whatever crumbs she’s offered; consequently, she’s by far the more successful of the two, though still a very long way from the A-list. (Mostly, she does shitty horror movies, and it’s a big deal that she’s up for the lead in one of them.) Anna is abrasive, sarcastic, unafraid to challenge authority, and getting nowhere fast. Most of the movie takes place in Big Sur, where Beth and Anna have gone to spend the weekend in a big house owned by one of Anna’s relatives. Isolated in the woods, the pair quickly turn on each other: Anna’s toxic jealousy, apparent from the outset, starts to openly fester, and it becomes increasingly clear that Beth guards her own small measure of self-worth by deliberately sabotaging any opportunity Anna might have to get her own career rolling. The mutual hostility builds to possible violence and a Persona-style rupture, after which things get very weird indeed.

A little too weird, arguably. Always Shine doesn’t strive to be particularly subtle—Levine even opens the film with an epigram from model-agency founder John Robert Powers, referring to women as “the bowl of flowers on the table of life.” Instead, Takal, working with editor Zach Clark (who, like Levine, is himself a director; his Little Sister opened earlier this year), complicates this blunt thesis in innovative formal ways. Though Beth grouses about how many times she’s gotten naked onscreen (“Do you ever feel like a whore?” Anna cruelly asks), this movie repeatedly has FitzGerald and Davis take their clothes off, but frames them as chastely as ’80s network television. Experiments with non-linear editing and distorted sound instill a deep sense of unease, even before things start going south. Compared to these provocative, original ideas (including that early “audition” fake-out, which plays expertly on our unconscious assumptions regarding specific visual and aural cues), the narrative’s surreal third-act switcheroo feels somewhat old hat. Always Shine shines brightest when it lets these women be themselves, and the filmmaking provides the dissonance.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.