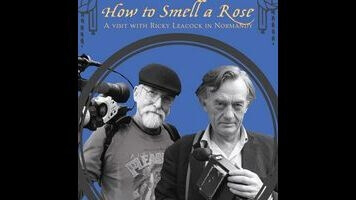

Two documentary legends spend a weekend together in How To Smell A Rose

The late Les Blank has been reintroduced to cinephiles as more than just the director of the Werner Herzog/Fitzcarraldo behind-the-scenes sketch Burden Of Dreams. That’s largely thanks to Criterion’s 2014 Always For Pleasure box set and the recent, long-delayed release of the 1974 rock-documentary A Poem Is A Naked Person. So for those new Blank fans, please note: How To Smell A Rose: A Visit With Ricky Leacock In Normandy is the documentarian’s final directorial credit, but isn’t really his “last film.” Blank had a habit of shooting footage just as a way of organizing and processing his wide range of life experiences, which is how he ended up with hours of video after a 2000 visit in France with fellow filmmaker and former MIT professor Leacock. Over a decade later, toward the end of Blank’s life, his occasional collaborator Gina Leibrecht—who was also on that trip—edited four days of their conversations into this hourlong film, which doubles as a Leacock bio-doc.

In a way, How To Smell A Rose is Leibrecht’s tribute to Blank as well, since so much of Leacock’s philosophy of art and cinema was shared by his houseguest. The British Leacock apprenticed with influential non-fiction filmmaker Robert Flaherty, from whom he learned the fundamentals of on-the-go shot-selection. He also discovered that the technical limitations of cinema in the ’40s and ’50s were preventing documentarians from achieving a necessary immediacy. Alongside Robert Drew, D.A. Pennebaker, and the Maysles brothers, Leacock helped develop the techniques and the equipment that led to the “direct cinema” and “cinema verité” movements of the ’60s and ’70s. These movements then led to the work of Blank, who, like Leacock, was inclined to pick up a camera and make movies “about nothing in particular.”

Blank doesn’t talk much in How To Smell A Rose, aside from asking the occasional question. But his interests and sensibility are all over the film—beginning with how he conducts interviews while Leacock is cooking a simple meal of cheese, bread, fresh endive salad, and chicken stew. A fascination with what the artist eats and how he prepares it leads naturally into a discussion of his general aesthetic. The title refers to the argument that there’s no “right” way to enjoy nature, or to compose a melody, or even to construct a sequence in a film. These are instinctive, individualized choices. That said, Leacock does advocate for his own method of making movies—with handheld cameras and no coaching of the subjects—as the ideal method to capture what he’s called “the feeling of being there.”

What’s not especially Blank-like about How To Smell A Rose is how much of a straight line it follows through Leacock’s reminiscences. The movie is less about hanging out with the director in Normandy than it is about hearing him describe his creative evolution—from the Flaherty years to when he revolutionized the form with his collaborative slice-of-life short films and features. (How To Smell A Rose is screening with one of those seminal works: Leacock and Joyce Chopra’s 26-minute, 1963 newsmagazine-style short “Happy Mother’s Day,” about how the birth of quintuplets in a small South Dakota farming community sparked a hubbub out of proportion to the family’s previously low-key life.)

But the ordinariness of this film—and the flatness of its video-shot images, relative to Blank’s beautiful-looking ’70s films—isn’t a significant drawback, given how eloquent Leacock can be. When he describes how the Robert Redford political satire The Candidate swiped a scene from one of his documentaries, the old professor has all kinds of illuminating comments to make about the ways that staging reality differs from just recording it as it happens. And Blank doesn’t even have to say, “Yes, I see,” because he understands those points implicitly.