“When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best.” This was just one of many fear-mongering lines Donald Trump spouted in June 2015 when he announced his candidacy for president, and it’s the type of rhetoric he’s continued to use to stoke his base from the Oval Office. His plans for a border wall appalled his more progressive constituents, and Trump’s only dialed things up from there. His administration expanded Immigrations and Customs Enforcement to unprecedented numbers and reach, and implemented (then rescinded) a “zero tolerance” immigration policy that tore children from their parents at the U.S.-Mexico border. And through it all, many (white) Americans have shaken their heads in denial, insisting that “this is not who we are”—meaning, presumably, that Americans and their government have not historically been so viciously opposed to immigration, so insistent on demonizing groups of people looking for a better life.

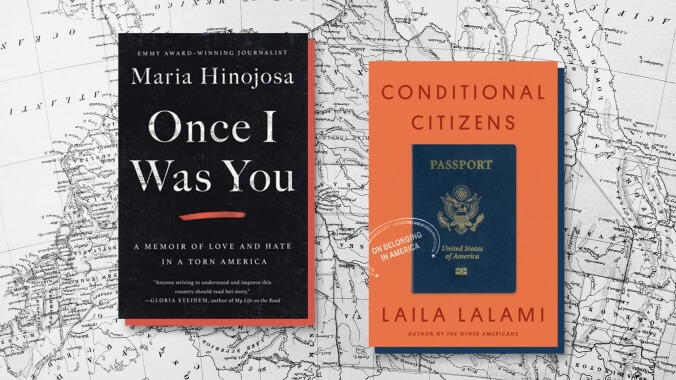

Two new memoirs released this month quickly and eloquently prove otherwise. In the first chapter of Once I Was You: A Memoir Of Love And Hate, Futuro Media founder and award-winning journalist Maria Hinojosa recalls immigrating to the U.S. as a young child—so young, in fact, that she was still regularly in her mother’s arms, clinging to her like “chicle.” The year was 1962, and the Hinojosa family was relocating to Chicago. The author’s father, Dr. Raul Hinojosa, had been recruited by the University of Chicago based on his innovative research on restoring hearing. His wife, Berta, was set to join him soon after, bringing their four children, including the memoirist. But as Berta prepared to present their green cards—“little pieces of plastic” that gave them “legitimacy” in their new country—at the Texas airport, the customs and immigration agent said a young Maria looked like she had “German measles” (in reality, it was an allergic reaction). The agent said the rest of the family could pass through, but he’d have to quarantine Berta’s youngest child. Hinojosa’s mother refused to have her daughter taken from her, and miraculously, the agent backed down.

Unfounded fear of disease, a compulsion to view outsiders as a threat, a policy of family separations—when it comes to immigration, things weren’t so different in the early ’60s. Early on, Hinojosa thought the customs and immigration agent’s behavior was the exception. “It had to have been a mistake,” she writes. Later, she realized there was “a room for babies like me, and I would discover that as I was writing this book. It wasn’t just a room. It was an entire system decades in the making.” Hinojosa then brings to bear her 30 plus years of reporting, tracing current immigration policy through the mid-20th-century, all the way back to the Naturalization Act of 1790, which limited naturalization to “free white persons.” She reminds us of the Mexican Repatriation, which saw the mass deportation of hundreds of thousands (some estimate millions) of Mexicans and Mexican Americans, including those with birthright citizenship, from 1929 to 1936. When Hinojosa details her upbringing in the multicultural Hyde Park neighborhood of Chicago, it’s against the backdrop of the Vietnam War, and the refugees who were quickly denigrated as “boat people.”

Once I Was You also reveals the extent to which the U.S. has imported and quickly exiled a labor force. Chinese immigrants build the Transcontinental Railroad, and were exploited in the same way that Mexican migrants were as part of the Bracero Program. Migrant laborers from Mexico and Central America were welcome to help rebuild New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, but only temporarily. Indeed, the history of anti-immigrant legislation is nearly as old as immigration: The Chinese Exclusion Act prohibited Chinese laborers from immigrating to the U.S., but only after the Angell Treaty of 1880 first suspended Chinese immigration. And again, the very basis for naturalization has historically been centered on whiteness.

Even as she recounts the racism she confronted throughout her career, Hinojosa remains conscious of her privilege; she grew up middle-class, and while as a mestiza Latina, she’s considered “brown,” she acknowledges the times that she and her Argentine roommate passed for white in college (specifically, in social contexts). The longtime Latino USA anchor notes the roles that colorism and anti-Blackness play in establishing a hierarchy even among the already excluded. When she delves into the notion of American exceptionalism and exceptional standards for immigrants, Hinojosa finds nothing but exclusion. Her father was highly educated and highly skilled—exactly the “type” of immigrant, along with Western Europeans without such bona fides, that has been deemed worthy of entrance into this country. As the recipient of the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award and the Edward Murrow Award, so is Hinojosa. That didn’t prevent her former colleagues from insisting that she had an “agenda,” that her investigative work was biased—as if the “objectivity” that’s reinforced the white, middle-class (and mostly male) status quo in journalism has fostered anything but bias.

Despite her exceptional work, many people still only saw her immigrant status. But as a lighter-skinned mestiza with class privilege, Hinojosa knows she hasn’t had to bear the brunt of anti-immigrant sentiment and xenophobia, the kind that puts an asterisk on the words of “The New Lazarus.” As Hinojosa writes:

America has always put forward a public veneer of loving immigrants and their role in this country, but in reality, the underside of immigration, the hidden hatred and internalized oppression and silence, has made our relationship with the notion of being a nation of immigrants much more embattled; a permanent secret war of words and hatred against itself.

Laila Lalami’s memoir,

Conditional Citizens: On Belonging In America, is a more concise read. But the novelist includes much of the same history that Hinojosa references, from the Naturalization Act to the progressive legislation of Immigration And Nationality Act of 1965. Although Lalami was college age when she first came to the U.S., there are a lot of parallels between her story and Hinojosa’s. Lalami had her own experiences with passing, albeit ones rooted in class: Her command of the French language granted her access in her hometown of Rabat, Morocco that her working-class parents never had. She is also highly accomplished: In 2015, Lalami was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction for her poignant and eye-opening novel,

The Moor’s Account.

Naturally, Lalami’s account diverges considerably from her memoirist counterpart’s; unlike Hinojosa, she traveled to the U.S. on her own, without thinking this was going to be her new home. But she came to embrace it, even getting married and relocating to California. Then the September 11, 2001 attacks happened—and suddenly, Lalami’s status was conditional. She became a naturalized citizen in 2000, but after 9/11, Lalami was eyed with suspicion by even her co-workers. She was expected to denounce all Muslims, to pick a side—this side—even as the U.S. military invaded countries that weren’t involved in the attacks, resulting in hundreds of thousands of civilian deaths.

Like Hinojosa’s memoir, Conditional Citizens readily acknowledges that these xenophobic sentiments are nothing new. But Lalami makes sure to distinguish the ways Islamophobia has informed domestic and foreign policy. The pressure to assimilate is placed heavily on all immigrants, but for Muslims, Lalami writes, failing to do so is a deal breaker. She quotes former President George W. Bush: “You’re either with us, or against us.” Although he was making that demand of international leaders, it’s been directed just as often at Muslim Americans. Lalami recalls having lunch with a coworker, who was taken aback by her acknowledgment of the high number of civilian deaths abroad. The novelist was expected, almost required, to weigh the loss of American lives against those lost in Iraq and Afghanistan.

For these reasons, assimilation plays a greater role in Lalami’s memoir than in Hinojosa’s. Though they’re both bicultural and bilingual, Hinojosa started to absorb U.S. culture and ideals from a very early age—they were never not part of her upbringing, even if she questioned them as she got older. Lalami, on the other hand, wondered about the country’s language, food, and customs because she had to reconcile them with the language, food, and customs she grew up with in Rabat. The distance U.S. leaders would put between the United States and Mexico (which once included large swaths of this country) demands assimilation for those deemed worthy of “conversion.” But, as Lalami persuasively writes, Muslim Americans are required to take the extra step of disavowing their religion and culture. Muslim Americans are conditional citizens because the terms “Muslim” and “American” are viewed by the dominant culture as diametrically opposed to one another.

But though the Muslim immigrant experience is one almost predicated on erasure, Lalami never loses sight of all the other conditional citizens in this country: The indigenous people subject to the Bureau of Indian Affairs; the Mexican migrants who were “decontaminated” with chemicals that were later used in gas chambers in Nazi Germany; the discrimination and violence against the Irish, Jewish, and Italian Americans in the 19th century and early 20th centuries. In detailing the history of conditional citizens, she cites former presidents Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama, who used terms like “illegal immigrants” to stoke nativism and support for their campaigns and administrations, and comes to the same conclusion as Hinojosa: Exclusion will come for even the exceptional.