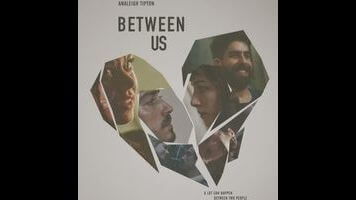

Two lovers scratch the six-year itch in the insightful but undercooked Between Us

Buying a home is a major life decision. It’s nothing, however, compared to the choice Henry (Ben Feldman) and Dianne (Olivia Thirlby) are really contemplating when they opt to finally move out of their rustic bohemian rental near downtown Los Angeles and buy an upscale condo on another, safer side of the city. Contently unmarried, these two thirtysomething artists recognize that jointly signing a mortgage is as big a step, if not a bigger one, than signing any license. It binds them, and not just financially. What they’re facing, six years into a relationship they’ve blissfully avoided thinking too hard about, is the possibility that they’re actually going to spend the rest of their lives together. And that’s a hell of a lot scarier than any bank loan.

Between Us, by writer-director Rafael Palacio Illingworth, is all about that moment when the looming reality of lifetime monogamy mutually sets in. Anyone who’s ever felt anxious about aging out of their wild years, settling down, and saying goodbye to the sensation of falling in love with someone new will recognize the tensions threatening Henry and Dianne’s happily ever after. Likewise, most of those who have been in a long-term relationship will see some painful truth in the couple’s cooling desire, out-of-sync sex life, and panicked response to the rough patch they’re skidding into. But if Between Us is crystal-clear perceptive on the big-picture stuff, it’s a little fuzzy on the details. And that’s because these lovers, who possess vaguely established creative vocations and little in the way of identifiable interests, aren’t as sharply defined as their problems. Plus, they have a habit of saying, with maybe only a hint of irony, things like, “I hate materialism. I love communism and Marx.”

It takes a talented actor to sell dialogue that clumsy, and to its credit, Between Us has two of them in the leads. Feldman, who played Ginsberg on Mad Men, and Thirlby, who’s probably still best known as the best friend in Juno, lend shading to characters whose personal and professional lives seem stuck at the first-draft stage. Henry is a filmmaker, but lllingworth conveys little about his work beyond a potentially metaphoric desire to make a time-travel film and one character’s remark that the way he shot a project “is so meta”—a line that could pass for a joke in a movie with a snarkier, more pronounced sense of humor. Dianne, on the other hand, creates multimedia exhibits or something for corporations. Do these people have hobbies or passions? Between Us provides a skeletal impression of their shared world. Only their romantic dilemma, their six-year itch, shifts into focus.

lllingworth at least exhibits a modicum of style, dressing up this fundamentally talky, intimate material with the striking (if on-the-nose) opening image of a storm cloud forming in a living room, as well as a sex scene shot in quick, close, expressive glances. He also adopts an interestingly asymmetrical structure. The film’s first half unfolds over a few months, time passing in a blur as Henry and Dianne begin to conform their lives to the common expectations of adulthood, including mulling the big leap into matrimony. Between Us then slows down to chronicle a single, tumultuous day, as the two embark on separate journeys into temptation—Henry drawn to a free-spirited musician (Analeigh Tipton) who takes an interest in his work, Dianne to a pair of men (Adam Goldberg, Scott Haze) who take an interest in her.

This backstretch—a kind of millennial riff on one of the ground zeroes of indie relationship dramas, John Cassavetes’ Faces—doesn’t pack the dramatic wallop it could. That’s probably because Illingworth has defined his protagonists almost exclusively through their relationship woes, to the point where their side love interests feel more like representations of their issues than fleshed-out people. Between Us is most compelling when it’s putting Feldman and Thirlby one on one, to talk about or around what ails their characters, in revealing tête-à-têtes or confessional voice-over. (The periodic narration, delivered from one lover to another, goes a long way toward making Henry and Dianne seem more developed than they are.) There are moments in the movie, like a spontaneous celebration that goes believably and woundingly awry, that express a lifetime’s worth of hard-hitting insight. Imagine how hard Between Us might have hit if Illingworth had put as much thought into who these people are as he did into what‘s eating away at their happiness.