Two new Werner Herzog films remind that even great directors can miss the mark

Everybody whiffs sometimes. Even the world’s greatest filmmakers, the towering giants of international cinema, have their off days. Consider this an off week for Werner Herzog. The inquisitive German director, who moves freely between fiction and nonfiction, has made his fair share of follies to go along with the masterworks; the occasional misstep is inevitable for an artist of his productivity and eccentricity, one inclined to follow his muse wherever it might take him, from the deepest reaches of the South American jungle to the heart of the American prison system. But thanks to an unlikely overlap in distribution strategy, this Friday brings two unrelated Herzog missteps to American theaters—one a sweeping historical epic, the other an oddball philosophical treatise, both negatively received on the festival circuit. About as different as two movies by the same director can be, they still manage to share a dubious log line: A woman goes into the desert for research purposes and ends up finding herself, but thanks largely to the influence of a charismatic man.

Queen Of The Desert, which premiered in Berlin more than two years ago, is Herzog’s distaff spin on Lawrence Of Arabia, down to the “exotic” swell of its knockoff throwback score, the vast expanses of majestically arid terrain, and an appearance by the legendary British archaeologist himself. To be fair, T.E. Lawrence (played here by Robert Pattinson, summoning some Peter O’Toole cheekiness under familiar headwear) only makes a cameo. The film focuses instead on one of his contemporaries: Gertrude Bell (Nicole Kidman), the English writer whose travels through the Middle East earned her the respect of both British officials and the various tribal leaders she encountered along the way, as well as a key role in the restructuring of the region after World War I.

For Herzog, this particular life story is an opportunity to work in the sweeping episodic mode of David Lean’s classic, marking Bell’s path through the Arab world—literally, considering the number of retro transitional cutaways to a red line zigzagging across an old map, from Damascus to Petra. The director has several times before traced the footprints of predecessors and contemporaries: His Nosferatu The Vampyre played homage to Murnau without simply replicating his style, while the more recent Bad Lieutenant: Port Of Call New Orleans put a distinctively lunatic, uproariously funny spin on Abel Ferrara’s poker-faced policier. Here, though, Herzog’s edges are sanded down (no pun intended) by the demands of the white-elephant biopic. All lavish period detail and stiff upper lips, it’s a handsome bore—maybe the most dismayingly ordinary movie Herzog has ever made. (It’s certainly one of his most uncritical, somehow letting British imperialism off much easier than Lawrence Of Arabia did.)

Whatever imprint Queen Of The Desert makes belongs mostly to Kidman, who stresses Bell’s compassion, her fearlessness, her eponymous regality. The movie positions its trailblazing heroine as an early feminist icon: One transition cuts sharply from Bell humoring bloodless suitors at a turn-of-the-century soiree to her on horseback, thundering into frame and out of a ho-hum life. But this angle feels frequently at odds with the regressive romantic bent of Herzog’s script. A broken heart is about the only real motivation he provides Bell, who humbles and beguiles every character she encounters, but remains perennially hung up on her dead diplomat lover (James Franco), at one point asserting—in groan-worthy response to an admirer’s praise—that she’s “just a woman who misses her man.” Surely there was more driving this real-life adventurer than a widow’s eternal devotion?

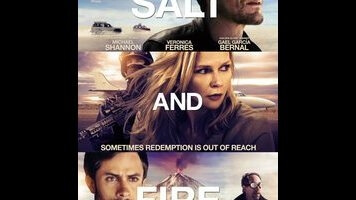

It’s possible that Herzog sees a little of himself in Gertrude Bell, whose fascination with extremes of human experience and the boundaries of civilization at least implicitly mirror his own. In Salt And Fire, it’s Michael Shannon who looks most like a surrogate for the man behind the camera—in part because there’s a sliver of Herzog’s one-time madman muse Klaus Kinski in Shannon’s thousand-yard stare, but also because the actor has been hired to recite such nuggets of wisdom as “Truth is the daughter of time” and “There is no reality, only views of reality.” Shannon plays Matt Riley, a mysterious corporate executive who takes hostage several U.N. delegates who have traveled to Bolivia to study an impending ecological disaster. One might assume that this CEO is just protecting his bottom line, but as he removes his mask and begins to ingratiate himself to one of his prisoners, Professor Laura Somerfeld (German actress Veronica Ferres), an alternative motive begins to emerge.

Though it has the potential makings of an urgent dramatic thriller, Salt And Fire never puts urgency or drama or thrills on the agenda. It’s a baffling exercise in intellectual masturbation, one that may or may not have grown from the globe-trotting volcano tour Herzog embarked upon for his recent Into The Inferno. There is, technically, a volcano involved here, too, but its destructive power remains entirely theoretical—it’s an abstract plot catalyst, there to inspire lots of turgid conversation between the two leads. The dialogue, if it can really be called that, oscillates from strictly expository—as during the moment when the delegation explains the purpose of its trip to a flight attendant, in the kind of detail only the audience might require—to deadeningly ponderous. (“Do you know what Nostradamus said about talking birds?” Matt asks Laura, during one sample exchange. “No, I don’t read Nostradamus,” she flatly responds.) Setting aside Shannon, who proved his compatibility with Herzog in the earlier My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done, the acting is likewise dire. Perhaps that’s intentional; it would be hard to accidentally make Gael García Bernal look like a rank amateur.

Clearly a future footnote on Herzog’s phone-book-thick resume, Salt And Fire eventually deposits Laura into the middle of the desert, where Matt strands her to care for a pair of blind boys and maybe have an epiphany. The experience is meant to impress upon her an urgent message, but it just comes across like condescending mind games—a controlling windbag mansplaining eco disaster to an expert in the field, while also giving her a forced crash-course in parenthood. That makes the Stockholm syndrome narrative not just silly, but kind of noxious. But the film’s real problem is that it’s a balloon of hot air, floating aimlessly in the South American wind. If Queen Of The Desert strays a little too far from Herzog’s wheelhouse, into the kind of bland respectability he’s always been too idiosyncratic to embrace, Salt And Fire has the opposite problem: It may be too damn Herzog for its own good. A movie cannot survive on endless pontification alone.