Movies that explore the relationship between a mother and her adult son are rare, which is one reason why last year’s James White, about a screwed-up young man struggling to care for his terminally ill mom, was so unusually affecting. Hailing from Ireland, Glassland represents another, far less successful effort in a similar vein. This time, Mom is a raging alcoholic rather than a cancer victim, but that works fine; the two provide equal opportunities for a great actor (Cynthia Nixon in James White, Toni Collette in Glassland) to perform arresting arias of anger and self-pity. No, the problem lies in writer-director Gerard Barrett’s conception of the son, who—decidedly unlike James White—has no real problems of his own and is merely doing the best he can with the lousy hand that life has dealt him. Glassland’s title is unexplained and somewhat cryptic (presumably, it’s meant to suggest extreme fragility), but there’s a reason why Barrett didn’t name the film after his protagonist: The guy’s sole function is to be an emotional punching bag.

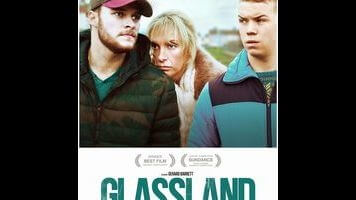

It does help a bit that he’s played by a superbly volatile young actor, Jack Reynor (probably best known for his role in Transformers: Age Of Extinction). All of the scenes between Reynor’s John and Collette’s Jean—note the symbolically linked character names—are beautifully performed by both parties, even when Barrett gives them pages of expository, theatrical garbage to recite. The worst offender by far is a nine-minute monologue Jean delivers at the film’s midpoint, explaining in laborious detail why she drinks herself into oblivion at every available opportunity. Collette pours her heart and soul into the speech, and Reynor provides superb silent reaction shots, but the words themselves—which largely involve Jean’s casual revulsion toward her youngest son, Kit (Harry Nagle), who was born with Down syndrome—are a ghastly mix of ostensibly shocking candor and implausible self-awareness. Jean is such a monster, and John such a put-upon sweetheart, that Glassland offers little more than undiluted bathos for over an hour.

At that point, Barrett realizes he needs some kind of dramatic motor, especially since he’s found nothing of consequence for John’s generically mouthy best pal, Shane (Will Poulter)—the film’s only other notable character—to do. So he has John, who’s understandably weary of retrieving his mother from random doorways where she’s passed out, or rushing her to the hospital when she collapses in a pool of her own vomit, persuade Jean to check into a rehab center. A shelter can offer her a free bed for a week, but a proper facility will cost thousands, and the only way John, who drives a taxi, can scrape up that much dough in a hurry is to volunteer for criminal work, conveniently offered by his dispatcher. Barrett does set up potentially shady activity early on—most of John’s fares seem to be prostitutes—but Glassland’s third act is deliberately, terminally vague (as distinctly opposed to “ambiguous”) regarding exactly what deal with the devil John has made in order to buy Mom a chance at getting the help she needs. The script is consistently either overexplicit or undernourished, and there’s only so much two fine actors can do.