In the European and Japanese markets, comics about cooking aren’t uncommon. Take, for example, Yuto Tsukuda and Shun Saeki’s Food Wars!—a popular, slick serial that runs in Shonen Jump magazine. In the United States, cooking is portrayed similarly to any other kind of action in modern mainstream fighting comics: It’s fast-paced and exciting, in much the same way that the best American cooking competition shows are, and it demonstrates that activities that might not seem visually interesting can easily be rendered as such. And yet, even with so many examples of how to make the subject compelling, there hasn’t been a successful American cooking comic. James Stokoe’s Wonton Soup is probably the most memorable attempt, but that was stymied by its author’s propensity for digressive career moves. But the latest effort at delivering a well-received cooking comic into the American marketplace has promise.

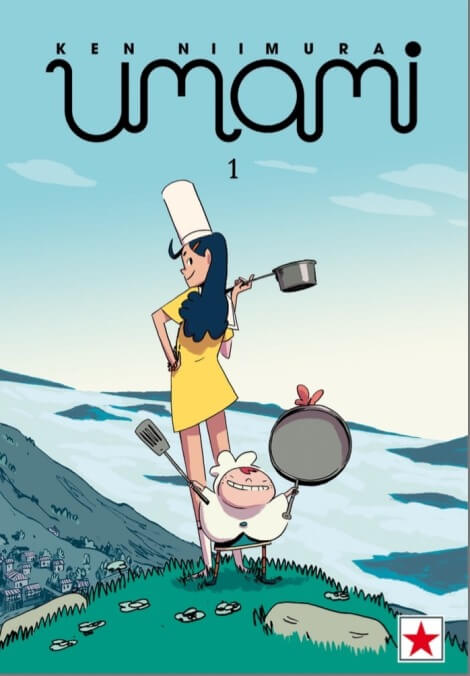

Like Stokoe, Ken Niimura tries to overcome the reluctance of American readers to try something new by couching his cooking comic, Umami #1 (Panel Syndicate), in a recognizable generic form: high-fantasy. He also conceals the cooking part. The new series tells the story of two quaintly named characters, Uma, a “cook,” and Ami, a “chef,” as they set out on a quest toward “the capital.” They meet when Ami’s cookbook gets stolen by the giant, angry chicken roosting on top of the building that Uma is squatting in. What adventures await them remain to be seen, but the book’s title page features the inscription “It takes two to cook: the adventures of a chef and a cook,” which implies a centrally important relationship between these characters-as-metaphors that Niimura will develop as the series continues.

This first issue, while light on plot, does still have a lot to offer readers. Niimura—best known for his 2008 collaboration with Joe Kelly, I Kill Giants—brings his familiar aesthetic to bear on a fantasy world that recalls the early entries in the Final Fantasy series. Moving among the European, American, and Japanese comics industries, Niimura has cultivated an aesthetic that draws on various traditions while standing somewhat to the side of them. His sense of movement and energy recalls fighting or even comedic manga, while his use of narrative captions is closer to how American comics writers tend to use them. And his books, like 2015’s Henshin, are typically printed in a size closer to the European album format. All of that is on display here (except for the size, unfortunately), and you can even see Niimura leaning into certain aspects of his work more fully than he has before. For example, the book’s second page is a simple image of a landscape, but the stroke of every line is visible; the hilly scene is textured with a palpable sense of energy, movement, and excitement. Niimura’s writing is light and accessible, but his unique aesthetic, which appears to be at once childlike and highly refined, provides more than enough reason to return to his work again and again.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.