Under current rules, there’s no way adventurous animation can compete at the Oscars

To realize the shameless disdain many Academy members feel toward the Best Animated Feature category—and toward animation in general—all one has to do is read a handful of those dreadful, anonymous Oscar voter interviews featured in trade publications every awards season. There are those who unapologetically note that they didn’t watch all the films in contention and even let their children pick which nominee to vote for. Others simply state they never watch “cartoons” at all. In either case, their dismissive attitude only perpetuates the erroneous belief that the medium’s sole purpose is to entertain young audiences. Best-case scenario, those with a lack of curiosity in, and appreciation for, one of the most vibrant forms of filmmaking might abstain from the privilege of awarding recognition in that category. Instead, their apathetic participation only helps major studios win year after year.

Until recently, one could take solace in interesting animated films at least getting nominated. Before 2018, the five finalists for Best Animated Feature were chosen by artists in the specific branch of the Academy dedicated to animation. Which is to say, the nominees were selected by a smaller, more knowledgeable, and inherently invested group of people. This resulted, occasionally, in some genuinely offbeat movies competing alongside expensive studio fare. Take, for example, the wonderful Brazilian feature Boy And The World, which earned a nomination in 2016 and only had a budget of about half a million dollars (chump change in comparison to American productions). That year, Illumination’s Minions, which went on to gross over $1 billion worldwide, didn’t make the cut. The previous year, GKIDS, a New York-based distributor of independent and international animation, slipped into the race with small gems from abroad, Song Of The Sea and The Tale Of The Princess Kaguya, while the enormous hit The Lego Movie wasn’t nominated.

Although GKIDS became a major player in the Animated Feature category this past decade, it has yet to take home the trophy. That’s because once the top choices are put forward, the entire membership of the Academy selects the winner, which usually gives Disney’s marketing powerhouse the upper hand. That advantage has only solidified following the 90th Oscars, when the Academy decided to allow members from all its branches to vote on the nominees in the category, too. The result of this populist initiative was immediate, with the subpar The Boss Baby and Ferdinand earning spots on the final list. Maybe this was the intention of the rules change: Studios were probably displeased that, during the larger part of the 2010s, their behemoths were losing out on nods to movies with minuscule budgets. The Oscars are nothing if not another way to increase Hollywood’s revenue stream.

Intentionally or not, opening the category to a broader voting body has functioned like a new form of gatekeeping, making it more difficult for outside voices to break in. This year, Wolfwalkers is almost guaranteed a nomination, and though it deserves one, the film will also earn it in part because GKIDS has partnered with Apple to distribute the film in the States. It’s almost certainly the smallest animated project the Academy will acknowledge this cycle. Under the new rules, there’s just little hope for something as worthy but idiosyncratic as Mariusz Wilczynski’s Kill It And Leave This Town. Which is a shame, because this unconventional Polish movie, denied anything like a for-your-consideration push, expands the very idea of what animation can accomplish.

For the last two decades, Wilczynski has built a portfolio of animated shorts and live animation performances—he draws animated sequences in front of an audience, often with a musical accompaniment—that has positioned him in closer proximity to fine-art circles than mainstream animation. (He’s enjoyed showcases at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and London’s National Gallery.) In other words, his work is expressly not for children. Of course, adult-oriented productions, like Persepolis and Chico & Rita, have competed for the Oscar. Most of them, however, have boasted traditionally satisfying stories. Kill It And Leave This Town isn’t just targeted toward grown-ups; it’s also designed to challenge them, aesthetically and narratively.

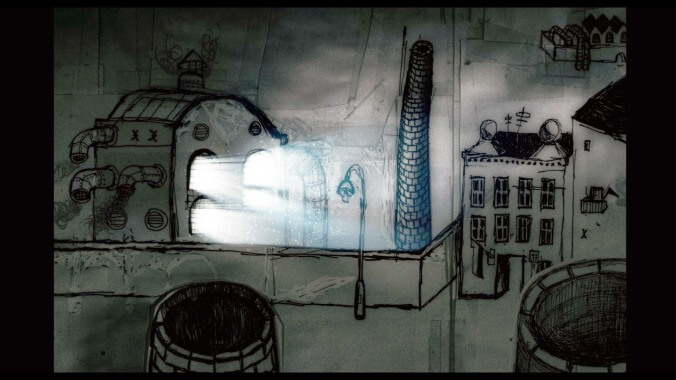

Moving his often purposefully disturbing use of the medium to a larger canvas in order to reckon with personal regrets and remembrances, the film is an animated memoir of the unconscious that took Wilczynski around 11 years to complete with a skeleton crew. He created virtually every frame himself. The town the title refers to is the artist’s native Lódz, where Wilczynski grew up during the 1960s when Poland was under communist rule; it acts as the setting for him to explore his childhood and his relationship with his parents in dark vignettes that don’t obey any logical understanding of time and space.

There’s a melancholic beauty to the characters and backgrounds that departs from the pristine imagery familiar to most big-studio animation. Human figures in Kill It And Leave This Town are grotesque, and so is the content of these dark dreamscapes: a decapitated head viciously attacked by crows, a humanoid cat that speaks in demonic riddles, etc. Wilczynski’s rustic, hand-drawn animation suggests scratches on lined paper brought to life. His process is not that simple, of course, but that’s the quality evoked—of witnessing something that comes directly from the artist’s hand to the screen.

This sensation is emphasized by the presence of an animated Wilczynski, listening to the adults argue over his love for fantastical stories and, later, observing a romantic night between his progenitors like a giant time traveler. An underlying regret marks several sequences where the storyteller, through the magic of animation, revisits instances in which he could have spent more time with his loving mother but didn’t. The same goes for a fraternal bond with a musician friend who passed away, like Wilczynski’s parents, before they could get closure. Industrial, impoverished landscapes introduce us to the hostile context in which his worldview developed, not as a lament but rather an honest and unvarnished recollection of the mental pictures he cherishes for better or worst. Kill It And Leave This Town is the opposite of an idealized depiction of the past, even as it gets across a powerful sense of nostalgia.

In harnessing animation for autobiography, Wilczynski has by design created something that could be deemed impenetrable or too obtuse. Asking us to enter his head via scratchy line work, the filmmaker tackles mature and ambiguous themes without the safety net of a neat resolution—or, for that matter, anything resembling a concrete beginning, middle, and end. That’s a big ask for those incapable even of sitting through the facile existentialism of some Pixar movies or the pop culture-heavy comedy of DreamWorks.

To celebrate Kill It And Leave This Town, which is eligible for the Oscar, would be to look past profits and honor the limitless possibilities of animation (something the Animated Short category better acknowledges). Unfortunately, instead of pushing toward a system that values all films regardless of their publicity brawn, the Academy seems to be heading in a seemingly more democratic but actually more exclusionary direction. Mere weeks ago, they did away with the executive committee that ensured more audacious submissions got a fairer shot in the Best International Feature category. Lo and behold, the short list put forward by the larger group is regionally diverse but features several broad films with generic middlebrow appeal.

Maybe it’s unrealistic to expect the Oscars to push the public toward bold visions, animated or live action. This is an awards body, after all, that consistently expresses a lack of interest in films that don’t fit their mold. But at least with Best Animated Feature, one can point to a time when the system somewhat worked and the GKIDS school of animation elbowed its way into the race because folks who cared were in charge. Without the Oscars love, it’s uncertain whether the company or the individual filmmakers nominated would be where they are today. Letting an uninterested mass of voters limit who gets to benefit from the exposure of a nomination, mostly in favor of congratulating the animation houses with the big bucks for billboards and magazine ads, is far more elitist than a curatorial selection committee. With these “niche” categories of films, wouldn’t it be better to let those who are committed to their advancement decide what warrants accolades? Even under the Academy’s earlier rules, a film as abstract as Kill It And Leave This Town would likely be a long shot. But at least the lineup wouldn’t be determined by whether or not someone’s grandchild got a cool McDonald’s promotional toy.