As we approach the longest day of the year later this week, one could certainly take advantage of the extra daylight and warm weather and spend some time outside. Drink a drink on a porch, take a boat out on a body of water, or even just go for a walk. Or—but really, and—one could use the extra daylight to read, either outside or by the gentle, natural light coming through one’s window. From a sci-fi master’s short story collection, to an incendiary feminist novel, to a warm, gritty ode to America’s fourth largest city, we’ve already read some excellent books in the first half of 2019 that have also earned their fair share of praise elsewhere. But what about the books we love that haven’t quite risen to the fore of the conversation? In addition to this year’s blockbusters, we’ve been digging the following books, which have either flown under the radar or deserve just a little more love. There’s a pair of surrealist short story collections in translation, a novel from a writer who’s had little trouble earning attention in the past, the latest entry in a genre we’re calling “Anthropocene feminist fiction,” and more. Add them to your stack. You’ve got some extra time this week.

Mouthful Of Birds by Samanta Schweblin (trans. by Megan McDowell, January 8, Riverhead Books)

My favorite genre of late is what might be called Anthropocene feminist fiction, literature that wrestles with the lives of women staring down a world’s end brought upon by men. The best of these novels—Megan Hunter’s The End We Start From, Sarah Moss’ Ghost Wall, and Samanta Schweblin’s Fever Dream—are much like life: brief, terrifying, and obstinately weird. Fever Dream is perhaps the strangest of all: the chronicle of a poisoned river, a sickbed ghost tale, a hallucinatory horror story that more than earns its title. The collected stories in Schweblin’s Mouthful Of Birds, first published in her native Argentina in 2010, likewise bathe in a surrealist delirium. Here, new brides find themselves abandoned in the darkness of a rural highway, a teenage girl devours live birds, a father crushes a butterfly and loses the person he loves the most. [Rien Fertel]

Following a brutal encounter with the police outside her home, an Indian-American woman lies bleeding out on the concrete. An inevitability, one senses. In those moments, Mother—as she is called in Devi S. Laskar’s singularly sharp novel The Atlas Of Reds And Blues about life in the shadow of confounding racial brutality in America—recalls her life in fleeting memories, a mishmash of unresolved stories. It makes sense that a poet would write such a book: the novel, like memories, is prismatic and free-flowing. Unsparing, too. As Mother bleeds, she thinks, “A miscarriage of a different kind. No baby to lose this time. A different kind of secession.” It’s an unrelenting story, but the way Laskar renders it is vital. Mother, of three daughters, and the child of Bengali immigrants, is often kind, cruel, tired, practical. And dying for no reason at all. [Kamil Ahsan]

The Heavens by Sandra Newman (February 12, Grove Press)

Remember that house party in your early 20s where you met someone so interesting that you wanted to keep talking to them all night? Reading a Sandra Newman novel feels like that, and it’s actually how The Heavens begins. In an alternate version of New York City—where a female Green Party candidate won the White House—Ben falls in love with a “Hungarian-Turkish-Persian” artist named Kate at a party. The thing about Kate is, every night she dreams about living in 16th-century England as a woman named Emilia, and having an affair with William Shakespeare. In fact, it’s more than a recurring dream to Kate—it’s a second life. Newman is one of the smartest and funniest writers on Twitter, and this weird, addicting, masterful novel should catapult her to further acclaim. [Adam Morgan]

Valeria Luiselli’s Lost Children Archive deserves a second look. Experimental, to a fault perhaps, Luiselli’s novel is the chronicle of a great American road trip, the story of a marriage breaking apart, a loving endorsement to raising children, a devastating commentary on U.S. history, a damning dissection of the nation’s modern immigration policy, and so much more. Combined, Luiselli has created, in the words of a character, an “inventory of echoes.” And no moment in Lost Children Archive will echo with readers like its climactic chapter, an agonizing, ecstatic 20-page, single-sentence masterpiece of imagination and creation. Kudos to Luiselli for conquering the art of the very long sentence (long the purview of men), and for writing a novel that seemingly takes on everything. This is the half-year’s most important book. Take the trip. [Rien Fertel]

The Parade by Dave Eggers (March 19, Knopf)

There’s a lot of Eggers out there, an Eggers for every reader. Postmodern-memoir Eggers. Tom Hanksian-Hollywood-vehicle Eggers. Great-American-novel-striving Eggers. Coffee-as-capitalism Eggers. Rewriting-kid’s-classics Eggers. And then there’s the odd, allegorical thriller Eggers. The Eggers that gave us Your Fathers, Where Are They? And The Prophets, Do They Live Forever?, a short novel, told entirely in dialogue, about American violence. Earlier this year, he published The Parade, a short novel also about American violence. Here, the pseudonymous government contractors Four and Nine are tasked with paving a highway, connecting country to capital in an unnamed war-torn country. An odd couple—Four is authoritarian and all business, Nine is inclined to dreamy declarations like, “The road is a highway of life”—they represent the flip sides of the American experiment abroad, remaking the world in our image, one doomed kilometer at a time. [Rien Fertel]

Flowers Of Mold by Ha Seong-Nan (trans. by Janet Hong, April 22, Open Letter)

Garbage, noise, traffic, the claustrophobia that comes from living among millions of people. Most of the stories in Ha Seong-Nan’s Flowers Of Mold are set in Seoul or its outskirts, and they emphasize the grimiest, most stifling parts of big city life. The walls are thin, and the neighbors make your business theirs—if they’re not going through your trash, they’re stealing your husband. Fitting to the book’s title, the characters’ arcs bend toward ruin in this, Ha’s first book-length publication in English (published originally in Korea in 1999). Coincidences, and there are many, rarely work in anyone’s favor. Wrapped up in fantasy or dreams, these men, women, and children are often confused over what is and isn’t real, the reader seeing before they do how their anxious yearning will go unfulfilled. As in opener “Waxen Wings,” wherein a growth spurt spoils a girl’s gymnastic promise, the strongest stories make clear these poor souls’ doom from the start. There’s something refreshing about Ha not giving them respite from bad luck and double crossers, the greasy oil of the fryer and the drunks pounding on their doors at all hours of the night. As one character puts it, “There’s nothing more telling than vomit.” [Laura Adamczyk]

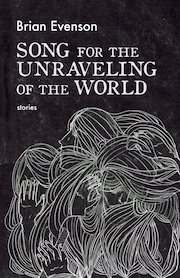

I’m not convinced Brian Evenson is entirely human. His literary horror fiction is just too good, too immersive, and too alien for a mere mortal. This book has everything one comes to expect from Evenson—brief glimpses of dark worlds where no one is completely sure where they are, who they are, or what is real. Like his previous collections, about half of the stories in Song For The Unraveling Of The World are set in our own reality, but my personal favorites have always been Evenson’s forays into science fiction. Here, the survivors of an apocalypse live beneath a half-destroyed skyscraper, astronauts awaken early during a long journey between stars, and siblings live in an unknown structure “in two places at once,” where one door leads to a barren plain and the other, total darkness. Every story is fascinating and leaves you wanting more. [Adam Morgan]

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.