Unfriended ingeniously commits to its laptop horror gimmick

Writing about horror movies that present themselves as raw documentary footage is an exercise in creatively repeating yourself. How many different ways can one say, “Enough already”? Yet for every 100 played-out variations on The Blair Witch Project, a single novel spin on the mock-doc formula presents itself. Unfriended, a fiendishly clever new fright flick, may be the most ingenious addition to the genre since the original Paranormal Activity. The film unfolds entirely within the frame lines of a teenage girl’s laptop screen, its characters squeezed into the tiny boxes of a group video chat, its protagonist toggling frantically between various browsers as her evening web time becomes an online nightmare. There’s some precedent for this premise—last year’s Open Windows attempted something similar, as did the Joe Swanberg short in V/H/S—but the filmmakers here completely commit to their gimmick, turning its limitations into benefits and exploiting the chosen technology for maximum effect. In the process, they hit the refresh button on the entire found-footage format.

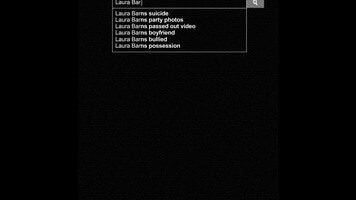

Unfriended transpires in real time, through a series of seamlessly connected long takes that put a sinister twist on the mundane interface many of us spend our days navigating. On the one-year anniversary of their classmate’s suicide—an extreme response to a humiliating viral video that made the social-media rounds—six high-school friends find their Skype session intruded upon by an anonymous avatar, silently eavesdropping on their group conversation. Soon, the teens begin receiving threatening messages from the dead girl’s Facebook and Messenger profiles. Damning secrets are disseminated. Incriminating photos are shared. Gradually, the tactics escalate from trolling to violence. Is there a ghost in the machine, or is someone acting on the behalf of the deceased?

Broken down to its essence, Unfriended is a slasher movie, a revenge flick about a bunch of faintly unlikable kids being harassed by someone who knows what they did last April. It’s the execution, the sheer formal ingenuity, that will make horror buffs reach for the “like” button. The film turns the quirks and glitches of modern technology into tools of the scaring trade. Every frozen webcam image generates suspense, every interruption of the video feed is a strategic blackout. (For once, it’s not hyperbolic to use the expression “pinwheel of death.”) The innovation extends to the film’s narrative tricks, too, as director Levan Gabriadze and screenwriter Nelson Greaves shrewdly dole out exposition through their main character’s browsing habits. Instead of flashbacks, there are guilty peeks at the “see friendship” section of Facebook. Instead of the customary third-party expert, brought in to explain the horror that’s happening, there’s an ominous message board. In one of the movie’s slyest moves, information regarding the dead girl’s traumatic past is subtly revealed in a chat window, as someone waffles about what she wants to say, typing and retyping the words until she finds a suitably cryptic explanation.

Unfriended turns out to be more entertaining than terrifying, though the kill scenes—flashes of gnarly gore, the buffering connection creating rhythmic cutaways to black—are suitably shocking. At times, the movie operates as expert black comedy: A high-stakes round of Never Have I Ever is like the opening set piece of Scream by way of the polygraph episode of Community. (No, really.) But there’s also a certain razor-sharp insight to the film’s take on cyberbullying. Like Blair Witch, this is a movie about technology as a barrier; the characters use the internet as an opportunity to indulge their cruelest impulses from a safe distance. The killer, in turn, uses the open forum of the web as a weapon against them—laying out their crimes and secrets for the world to see, disclosing the true colors they reveal only anonymously. Unfriended may be a stunt, but in its diabolical employment of everything from pop-up ads to Chatroulette to Spotify, it also feels very much like a horror movie of the moment. This is how we terrorize.