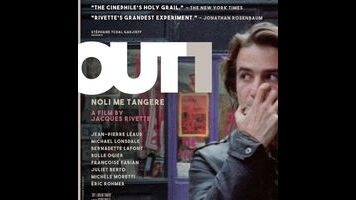

Unique and monumental, Out 1 is the most paranoid movie ever made

As strikes and riots shut down France in May of 1968, slogan graffiti spread like kudzu over the sidewalks, one of the best-remembered being: “All power to the imagination!” Jacques Rivette’s monumental Out 1 is set almost exactly two years later, in a hazy “What now?” where imagination is just about all people have left of those earlier days—and the thing about imagination is that it’s solitary and private, and not much of a substitute for the high of thinking everything is about to change for the better. Uniquely ambitious, Rivette’s film (technically a serial) spends nearly 13 hours stitching paranoia, loneliness, comedy, and mystical symbolism into a crazy quilt big enough to cover a generation. And though its first-ever American release is bound to dispel some of the air of sacrament and mystery that has surrounded Out 1 for decades, perhaps it will now be better seen for what it is: the medium’s most indelible portrait of an era of lost ideals and a funky, one-of-a-kind vision of individuals searching to be part of something bigger and more meaningful than themselves, even if only as a delusion.

Partly inspired by dream-like, silent-era Louis Feuillade serials like Les Vampires and Fantômas, Out 1 plants many of the best French actors of its time into a plot that can only be explained with Venn diagrams and flowcharts, involving two scam artists, two experimental theater troupes, two Ancient Greek plays, a boutique shop, a secret society modeled on Honoré De Balzac’s History Of The Thirteen, and cryptic messages decoded through Lewis Carroll’s “The Hunting Of The Snark.” This is 1970—the real 1970, not a tasteful recreation—and people wear neckerchiefs, shearling coats with toggle buttons, gypsy prints, leather jackets, and pants with flared legs. Shot largely handheld on 16mm, Out 1 could pass for a documentary on what it meant to dress and live hip in the streets and unevenly painted bohemian spaces of Paris in that era. In stretches, it has the off-the-cuff luster of color street photography, with cinematographer Pierre-William Glenn’s frames bursting with the purples, pinks, and greens of fabric and paint, made tactile by the fuzz of film grain.

At the same time, it could just as easily pass for a documentary about itself, given Rivette’s taste for including flubbed takes, camera noise, crew shadows, and curious bystanders. This slipshod quality could be interpreted as a further homage to silent film, specifically the rough location shooting of the ambitious French movies of the 1910s. (One of Feuillade’s most paranoid movies, the short Erreur Tragique, actually uses this as a plot point; it’s about a man who becomes convinced that his wife is having an affair after spotting her in the background of a movie.) Could be is the operative phrase here, because these are really just side effects of a mind-bogglingly complex project being shot very quickly and cheaply. Generally, these would be left on the cutting room, but they are included here, part and parcel with characters who read sinister meaning in coincidence and nonsense.

Out 1 can sometimes seem too real (see: an acting troupe’s intensely physical improv exercise, shot in a single take that runs almost half an hour), but it’s mostly about the unreal: the world of theater, or maybe the world as a theater, full of masks and assumed identities, with actors playing actors, rehearsals doubled by small-time cons, and characters fading away into their obsessions. Here, that old prop of paranoid logic, the blackboard covered with obscure references and circled words, becomes a window into a character’s yearnings, the dots connected because each link represents a step closer to fulfillment, if not closure. At one point, filmmaker Éric Rohmer appears in an extended cameo, wearing one of the most fake beards ever committed to celluloid. Out 1 is the kind of movie that invents its own dimension, and here, a bad disguise constitutes reality. It’s all make-believe and play—and one can’t help but wonder whether the riots of May ’68, which hang over the movie like an overcast sky, were too.

Like much of the vanguard of the French New Wave, Rivette started out as a critic at Cahiers Du Cinema, the little French film magazine that ended up defining much of the way we talk and think about movies. He was one of the first Cahiers critics to start making movies, and one of the last to take up film full-time, staying on as the magazine’s editor while peers like Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, and Claude Chabrol became internationally renowned. It was only after the political turmoil of 1968 that he came into his own creatively, developing a distinct voice captivated by theater, conspiracy theory, and supernatural fiction, and marked by a spacious and adventurous relationship with actors. Despite its outsize ambition, Out 1 is actually an early work, first screened in a rough version in 1971, but restricted for decades to one-off screenings and a couple of TV broadcasts.

It’s broken up into eight chapters, usually shown four at a time over two days, each titled to suggest a change of point of view. (E.g., “From Lili To Thomas,” the title of the first chapter.) Out 1 is founded on ironies: It recalls the early years of fiction film, but is very much of its time; it has a vibe of adventurously unvarnished realism, but is about the fake and fantastic; and it’s staggeringly big, but looks very small. The most important of these ironies is the fact that Out 1 is all about things that only happen and exist in headspace, but focuses on relationships between dozens of characters. There are four major characters, each of whom makes their living by pretending to be someone else: Thomas (Michael Lonsdale), the leader of one of the theater groups; Emilie (Bulle Ogier), a mother of two with a missing husband, who runs a hippie shop as one “Pauline”; Frédérique (Juliet Berto, who went on to star in Rivette’s breakthrough, Celine And Julie Go Boating), a grifter who pretends to be an easily seduced virgin in order to rob skeezeball barflies of their cash; and Colin (Jean-Pierre Léaud), who walks up to cafes playing harmonica so badly that people pay him to go away, and harbors a secret best left unrevealed.

Out 1 is nothing if not a sprawling showcase for different acting talents and styles, everyone given room to dig deep into their character’s psyches, improvising from outlines written by Rivette and Suzanne Schiffman, one of the shadow talents of the New Wave. In large stretches, the movie’s mixture of improvisation, obsessive paranoia, and documentary stirs into a thrilling collision of fiction and reality, as in a scene where Colin, spiraling into madness, is followed around by children who have just wandered into the shot, and have become part of the scene because of Rivette’s refusal to yell “Cut!” and Léaud’s refusal to break character. Squint at the right angle, and Out 1 seems kin to the novels of Thomas Pynchon, similarly steeped in genre pastiche and the sad afterglow of the ’60s counterculture dream. But whereas Pynchon’s fiction inhabits its own world of wordplay and silly names, Out 1 is always venturing out into open streets and uncontrolled situations.

In other words, this is the most thoroughly and authentically paranoid movie ever made, its overtones of conspiracy and cryptic meaning so pronounced that they extend the borders of fiction out into the real world; a viewer may exit the theater, but they don’t really exit Out 1 for a solid week after. With all of these mind games, hall-of-mirrors effects, and moments of emotional collapse, it’s easy to overlook the fact that Out 1 is also pretty damn funny, carried in part by its sense of humor. (Rivette’s five-hour Out 1: Spectre, cut from the same footage, is a very different film, in part because it isn’t very funny, and as a result is nowhere as devastating.)

Perhaps now, those outside the deepest end of cinephilia can walk into a movie known as the longest and most ambitious work of one of the most highly regarded cult figures of the New Wave, only to discover that it opens with a shot of leotard-ed asses sticking up in the air, with highfalutin avant-garde actors frozen in a stretching exercise that makes them look like a gaggle of ostriches. However, to anyone who’s sat through all of Out 1, that opening visual gag will retrospectively seem like a cryptic allusion to problems of perceptions—a credit to the invasiveness of Rivette’s paranoid vision, which turns everything into coded transmission and makes every accident feel like esoterica that needs to be deciphered.