Val tells the life story of Val Kilmer, in the words and through the camera lens of Val Kilmer

Kilmer's personal archive of home videos gives voice to his journey as an actor and cancer survivor

If you know anything about actor Val Kilmer outside of his iconic performances in films like Top Gun, Tombstone, and Willow, it’s probably that he’s a “serious artist,” embodying all the positive and negative connotations of that label. Kilmer’s someone who treats his craft with the utmost importance and, like a true Method devotee, completely commits to any given project. This kind of creative intensity inevitably garnered him a reputation for difficulty or perfectionism on set, which has been both upheld and repudiated by various cast and crew members over the years. Regardless of the veracity of those claims, however, Kilmer’s behavior is clearly a manifestation (or a misapplication) of his artistic devotion. It’s his sincere hope that if he transforms for a role, it will in turn transform him.

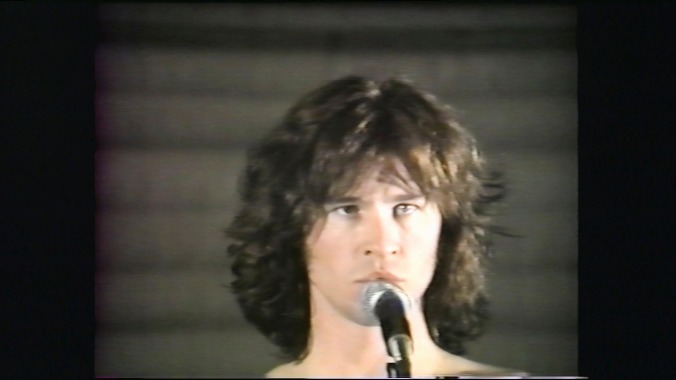

Kilmer’s raw vulnerability is on full display in the documentary Val, which chronicles the actor’s life primarily through a treasure trove of home videos and footage shot by Kilmer himself. His personal archive makes up the bulk of the film, so much so that he’s credited as Val’s cinematographer; from his early high school productions through his performance as Mark Twain in his one-man show Citizen Twain, Kilmer has compulsively chronicled much of his own life. Co-directors/editors Leo Scott and Ting Poo pare that material down to a mostly delightful highlight reel of his career. Some of the footage’s charm speaks for itself: There’s obvious fun in watching the young Top Gun cast check the paper for advertisements of their latest films, or seeing Sean Penn and Kevin Bacon moon Kilmer’s camera, or getting another look behind the scenes of the notoriously disastrous Island Of Dr. Moreau shoot. At the same time, the clips showcase lesser-known sides of Kilmer, like the goofiness that comes out when he’s with then-wife Joanne Whalley and their two kids. We also catch some of his casual fearlessness—the only way to describe his elaborate, slightly embarrassing audition tapes for Goodfellas and Full Metal Jacket, the latter of which he hand-delivered to Stanley Kubrick in London.

Val cuts between Kilmer’s own footage and contemporary scenes, which feature the actor post-tracheostomy after a two-year battle with throat cancer. With his voice impaired (he can only speak in a creaky rasp by pushing a hole in his throat; his words are subtitled), Kilmer felt compelled to account for his life and behavior as soon as possible. His resilience and good humor in the face of such physical damage is at once heartbreaking and inspiring, and it provides an intensely moving framework for Val, particularly because the film is such a family affair. The early sections feature many home videos of Kilmer and his brothers making movies on Roy Rogers’ old ranch, and his son, Jack, recites his father’s writings in voice-over. Much of the present-day footage is devoted to Kilmer traveling with his family, taking Jack to visit his old stomping ground of Juilliard or hanging out with his daughter, Mercedes. It’s clear that Val exists not just to remind the world of who Val Kilmer is and was but also to leave Kilmer’s children with an extended document of his younger self.

Nonetheless, Val feels stuck somewhere between a personal diary and a sales pitch; capturing the arc of an interesting life and convincing the world of Kilmer’s greatness are cross purposes. Scott and Poo might want the audience to draw their own conclusions about Kilmer’s problematic on-set reputation by juxtaposing a scene from the set of Dr. Moreau where Kilmer refuses to turn his camera off against director John Frankenheimer’s wishes because he’s “in a highly emotional state” against a montage of press coverage all but designed to dismiss this side of his persona. At the same time, that Val relies so heavily upon Kilmer’s archive and his willful participation hinders any chance for an impartial view of his behavior or beliefs. His Christian Science background, for example, is minimized (likely to ward off any thorny questions), despite it playing a major part in his parents’ marriage, his cancer recovery, and potentially his younger brother’s tragic death.

There’s an unresolved tension at play between the film’s conscious construction and Kilmer’s desire to present his unvarnished truth. It’s possible this is the film’s intention all along, considering it opens with Kilmer, through Jack, saying he wanted to make a film about acting that explores “where the actor ends and the character begins.” Maybe the Val in Val is another character he’s playing, and the life he’s presenting in the film belongs to “Val” instead of Val Kilmer. Nevertheless, the film still plays like a biography, and if the intent is to subvert that approach, the results are confused. If you’re already a fan of Kilmer’s work, there’s clear value in watching him pal around as a young man on the brink of stardom or rehearse as Jim Morrison for The Doors. But for everyone else, Val can sometimes feel like an uncomplicated victory lap.

It will also likely test the patience of those allergic to actorly pretension, but at least that’s somewhat offset by the humbling scenes of Kilmer going on the road to visit fans. He expresses reservations about capitalizing on his old career and image, amplified by a series of fans asking him to sign, “You can be my wingman,” on autographs at Comic-Con. But even these moments are undeniably touching, too, considering the physical toll it takes for him to make such treks. (It’s truly wince-inducing to watch Kilmer stop signing autographs so he can vomit in a trash can.) The actor’s acclaim during his commercial peak of the ’80s and ’90s was rooted in the idea that he was frequently the best element in otherwise imperfect films, that he stood out through sheer charisma and studious technique. Naturally, even after Kilmer’s star power declined, the cult surrounding him remained faithful. His appreciation and acceptance of this fact leads to some of Val’s strongest moments.

Throughout his career, Kilmer has doggedly pursued his whims within and outside the Hollywood system. By his own estimation, he never received many opportunities to do the type of acting he wanted to, either because of his reputation or because his moment had passed. Nevertheless, he’s kept pursuing pet projects at his own expense, like a film about the life of Christian Science church founder Mary Baker Eddy, which he tried to self-fund through performances of his one-man show as Mark Twain. His obsession with Twain might seem like another bizarre layer of an onion-like identity, but hearing him draw parallels between the author’s life and his own, particularly the family tragedies and the financial hardships, lends it some power. Val banks on various disparate, seemingly strange elements of his character—his spirituality, his personal fixations, his hunger to document his life—making sense as parts of a whole portrait. While it’s only occasionally successful in this regard, what comes through the most is the image of a man who reaches far beyond his grasp to be received among the stars on his own terms. That Kilmer is still doing this despite his physical setbacks and considerable loss is no small feat.