Shooting an entire feature film continuously, without a single cut, is a dumb idea. It was a dumb idea 67 years ago, when Alfred Hitchcock attempted to create the illusion of having done so in Rope (hiding the necessary edits by zooming into actors’ backs), and it’s still a dumb idea today, when lightweight video cameras make the feat genuinely possible. Even when it’s done with a sense of purpose—the best-justified example is probably Alexander Sokurov’s Russian Ark (2002), a whirlwind historical tour of the Hermitage Museum—it’s still fundamentally a gimmick, calling undue attention to its own virtuosity. (That’s especially true of Birdman, which pointlessly fakes a single-shot technique despite taking place over several weeks.)

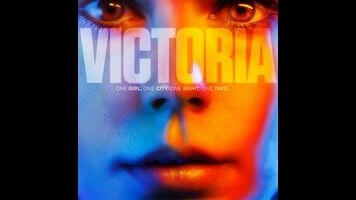

Victoria, a German thriller that unfolds in a single shot lasting two hours and 13 minutes, is even emptier than most such efforts. Director Sebastian Schipper and his heroic cinematographer/camera operator, Sturla Brandth Grøvlen (the latter gets top billing in the closing credits, appropriately) successfully mount a production that wanders all over a couple of Berlin neighborhoods, and the result is a logistical triumph. Good luck finding any point of interest other than marveling at the technical achievement, however. The film is certainly impressive, but “impressive” and “great” (or even “good”) aren’t remotely the same thing.

Opening in a strobe-lit underground nightclub, Victoria immediately locates its title character, a young Spanish woman (Laia Costa), on the dance floor, then follows her as she bumps into a quartet of friendly, playful young German men. One of them, Sonne (Frederick Lau), clearly has a crush on her, and he manages to persuade her to accompany him and his friends, at 4:00 a.m., to a nearby rooftop, where it’s revealed that Boxer (Franz Rogowski) has recently spent time behind bars. Soon, Victoria has agreed, rather improbably, to act as driver for the group on a vague job they say they have to do, which turns out to be robbing a bank at the behest of a gangster who’d provided Boxer protection in prison. While they get away relatively clean—even returning to the nightclub to celebrate—everything goes to hell shortly thereafter, with the camera in hot pursuit as Victoria and the others flee from the cops.

Right from the beginning, Schipper’s decision to capture the entire movie in one shot (he reportedly got it on the third take) bloats its running time for no good reason. He’s obligated to follow the characters in real time whenever they change location, and while he does his best to keep these jaunts short, and to fill them with behavioral detail, the first 45 minutes of Victoria would constitute perhaps 25 minutes in a film shot normally. And what’s gained, exactly? Cinema’s primary strengths are its ability to compress time and create meaning via the juxtaposition of images—for an example of both, think of the famous cut from bone to spaceship in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Insisting on following characters around with the camera trades both of those virtues for an ostensible uptick in urgency, though expert continuity editing arguably creates every bit as much breathless excitement as Steadicam pyrotechnics do.

Ultimately, though, the real problem with Victoria is that it isn’t about anything apart from answering the question, “Can we pull this off?” Costa makes Victoria herself immensely appealing—playful, curious, impulsive—but the character isn’t given much to do, apart from express some regret early on about her failure to make the grade as a concert pianist. Her decision to help these guys she’s just met rob a bank is never remotely credible. The back half of the movie (following the robbery, which is barely seen; the camera stays with Victoria in the car) is standard-issue lovers-on-the-run material, distinguished solely by wow it’s still that same shot that started an hour and a half ago! Having the characters return to the nightclub where the shot/story began seems expressly designed to call attention to the degree of difficulty (they’ve been all over the place by that point), and it works—you can’t help but marvel. But it’s like marveling at 20 square miles of dominos that, when toppled, spell out THESE ARE A WHOLE LOT OF DOMINOS. Well, yes. Mission accomplished. But was that really the best possible expenditure of that energy?

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.