It is hard to imagine a world without refugees. Border-crossers fleeing war ravaged communities; evictees seeking refuge from economic misfortune; the persecuted, the hated, the victims of floods, fires, and hurricanes. Climate change, we’re warned, will soon force millions of people, whole cities and countries, to pack up all that is worth taking—or, to be sure, that which is most portable—and just go.

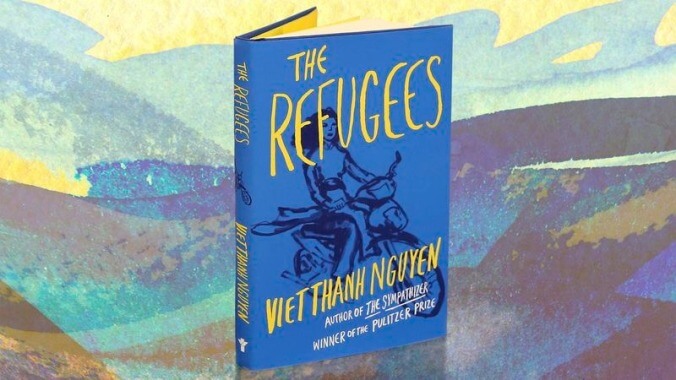

We are all refugees in the making, Viet Thanh Nguyen reminds us in his short-story collection, The Refugees, all potential exiles destined to be haunted by a place and the past. Nguyen’s debut novel, The Sympathizer, won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for fiction. His follow-up, Nothing Ever Dies, a series of essays on war, memory, and identity, was a 2016 finalist for the National Book Award in non-fiction. These earlier books were sparked by Nguyen’s experiences as a refugee of the Vietnam wars, but The Refugees, a collection of eight previously published stories, seems even more indebted to his life as a displaced person.

In “Black-Eyed Women,” the collection’s opener, and the strongest and most recently published among the group, the narrator, a Vietnamese refugee, works as a ghostwriter for individuals made famous for their suffering: “the kind that healthy-minded people would not wish upon themselves, such as being kidnapped and kept prisoner for years, suffering humiliation in a sex scandal, or surviving something typically fatal.” While at work on a particularly trauma-inducing memoir, the ghostwriter is visited by a ghost, her long-dead brother, a refugee from the living world, murdered and buried at sea while fleeing Communist Vietnam. She asks why he wears the same clothes he wore that awful day. “We wear them for the living,” he tells her. “The dead move on,” the ghostwriter learns. “But the living, we just stay here.”

Refugees, whether dead or alive, traffic in memories. Stories are the currency of those damned to survive. In “War Years,” another narrator recalls a painful episode from his boyhood, his mother’s feud with a Mrs. Hoa, who earnestly seeks donations in support of anti-Communist guerrillas back home, yet cannot come to terms with the decades-long disappearance of her own husband and son, both guerrilla fighters. “While some people are haunted by the dead,” Nguyen writes, “others are haunted by the living.”

In The Refugees the living are haunted by their lovers, their children, themselves. They are wealthy, poor, and middle-class. Tour guides, shopkeepers, and hucksters. They are Vietnamese, American, and Vietnamese-American. One mother is still haunted by “the fearful expressions on her children’s faces” who survived a journey on the South China Sea many years ago. A father is haunted by the nation he once flew over as a pilot—“if you’re going to bomb a country,” he says to comfort himself, “you should at least drink its beer.” His daughter now works as a teacher in a rural outpost in that country: “I have a Vietnamese soul,” she tells him, much to his disgust. Others are haunted by the strangeness of California, by months spent in refugee camps, by years, if not lifetimes, spent living in another world.

Fans of The Sympathizer might miss Nguyen’s finely filigreed prose, byzantine-absurdist plotting, and Kubrickian dark humor in these stories. Still, The Refugees will haunt its readers, especially in these times, when refugee stories need to be told, shared, and told again, ad infinitum. “Stories are just things we fabricate, nothing more,” Nguyen writes. “We search for them in a world besides our own, then leave them here to be found, garments shed by ghosts.”

Purchase The Refugees

here, which helps support The A.V. Club.