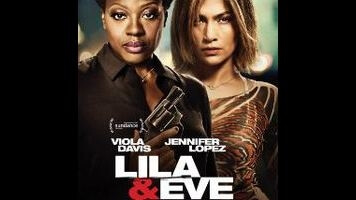

Davis plays Lila, an Atlanta city clerk whose teenage son is gunned down, seemingly at random, during a drive-by shooting. Frustrated by local detectives (Shea Whigham, Andre Royo), Lila decides to start her own investigation into her son’s death, accompanied by shearling-coat-clad Eve (Jennifer Lopez, who, per The Boy Next Door, seems to have a thing for movies that feel like parodies of themselves), a woman she met in a support group for mothers of murder victims. They bring along a revolver for protection, though it doesn’t take long for the trigger to get pulled. In between interrogating drug dealers and gunning down bad guys, the two women re-decorate Lila’s modest home. Director Charles Stone III (Drumline, Mr. 3000) strikes a self-serious tone that’s too understated for the movie to ever come across as howling camp, even as the plot grows increasingly ludicrous, throwing in clueless cops and a booby-trapped house that explodes in a digital fireball.

A dimly lit, psychological treatment of trashy pulp material isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but only Davis seems to have the skill set necessary to pull it off. The movie around her just feels uncomfortable with itself; when it manages to introduce serious tension—like having a murdered drug dealer’s mother join Lila’s support group—it defuses it awkwardly. What it amounts to is a whole lot of shrugs—about cycles of violence and the socio-economic realities of long-term grief—accompanied by near-compulsive, twitch-like winks about the aforementioned plot twist. The occasional shock of black humor (say, a drug runner falling to his death while trying to dodge bullets) or grim imagery does nothing but contribute to the impression of a movie struggling to decide on a point-of-view. But at least it has Davis, who can inhabit vulnerability and turn credibly scary with equal ease; in those moments when the camera locks in on her face, Lila & Eve almost passes for something graceful.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.