Vulnerable people are corporate assets in Test, an eerie comic showing where late-stage capitalism can lead

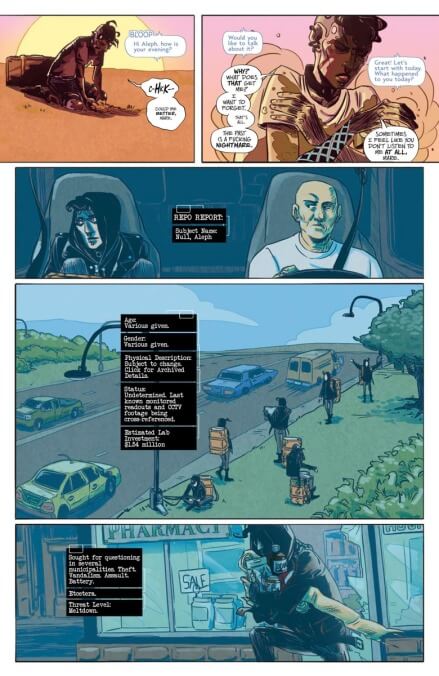

Test opens on a young person in the cab of an 18-wheeler, sparking anxiety in the reader about vulnerable hitchhikers and the threat long-haul truckers can pose. But expectations are thwarted as Aleph, Test’s protagonist and the fragile-looking young person in question, is released from the cab without incident and very quickly delivers violent acts instead of being the victim of them. This is the first of several moments where Test subverts expectations and twists back around on itself. At one point, panels progress backwards in order, and later on the story leaps to a flashback. But it’s easy to follow, and just as fractured as Aleph’s disorganized mind.

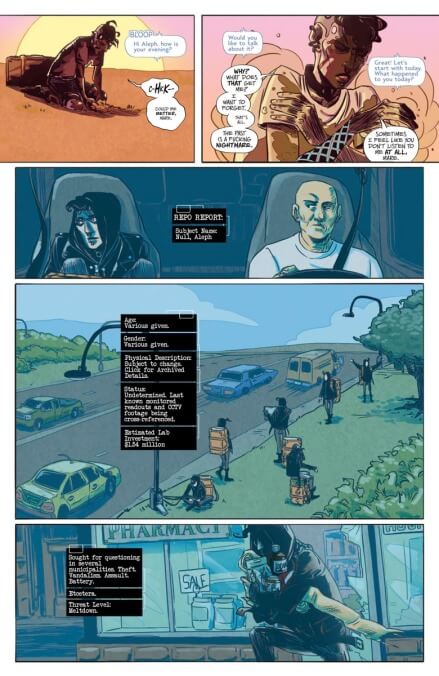

Aleph is on a journey to the middle of America, seeking a town that may or may not exist to solve a problem that only Aleph understands. There are echos of American Gods, with the strange isolation and sense of danger that comes from hiding in a small town in a flyover state. The Vault Vintage variant cover by Nathan Gooden and Tim Daniel is an intentional homage to Transmetropolitan, and both books feature body modifications sponsored by corporations. But it would be an overstatement to say that Test feels directly or even closely related to either one. Instead, the book occupies the center of a Venn diagram of genres and ideas, a testament to stories that have come before but fresh and unique in its own way. Test is in line with writer Christopher Sebela’s previous work, particularly Crowded and Dead Letters. In some ways, Crowded and Test feel like two sides of the same coin: Where Crowded is extrapolation of the gig economy and social media, Test shows a logical conclusion of late-stage capitalism and lack of healthcare options. Aleph’s body modifications are born of addiction and some inner demons of their own, but also born of a need for medical attention and income.

Laurelwood, the town that Aleph is looking for and ultimately finds in this first issue, unfolds as a strange, colorful combination of reality and hallucination. The implication is that the reader sees things as they really are—even though Aleph is posed as an unreliable narrator, it’s not clear if that unreliableness extends beyond Aleph’s perception. Artist Jen Hickman and colorist Harry Saxon make the lines between what is factual and what is inside Aleph’s blurry, spinning the reader out into Aleph’s confusion along with them. Aleph is the sole witness to a lot of things, and there’s doubt as to what can be firmly believed. But despite that, and the bad that Aleph does, they are sympathetic: androgynous enough to present as genderless, with the look of someone who never has as much as they need.

Saxon’s careful color palettes help distinguish between settings while staying cohesive overall, not so limiting as to imply that one thing or place is true and another is not. Aleph’s fractured, lyrical inner monolog takes up a lot of room on the page, and letterer Hassan Otsmane-Elhaou has to do a lot of heavy lifting. It helps to establish Aleph and the way they see the world, but it does make some pages feel cramped. Hopefully future issues won’t rely so much on Aleph speaking to themself or their potentially electronic companion, Mary, because Hickman’s work when Aleph is standing solo in a wide desert expanse and the pacing of silent creeping fears through multiple panels are compelling and deserve a lot of space to grow.

Test isn’t as overtly comedic or cartoonishly action-focused as Crowded, but fans of that book should check this one out. It’s definitely for readers that enjoyed Transmetropolitan and Private Eye, and the sorts of stories that warn us not only about the decisions that we make, but also the things we believe.