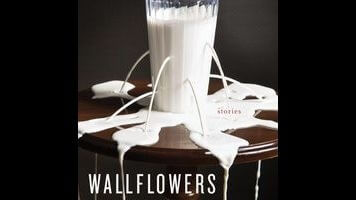

Wallflowers suffers from too much of a good thing

Eliza Robertson’s Wallflowers starts with a bang but quickly loses momentum. “Who Will Water The Wallflowers?”, the first of 17 short stories, begins with the promise of a flood as a teenage girl house-sits for a neighbor on a street of identical houses. A few hundred feet away, her mother’s routine is disrupted without her daughter. A neighbor man pays a little too much attention to the girl. Then comes the flood; the girl climbs to the roof of the house and scans the water-drenched landscape for her mother. The story ends there, on an unexpected but poignant cliffhanger.

There’s not much resolution to be found in this collection of short stories, each of which aggressively omits a clean ending. It’s a refreshing—if frustrating—change of pace from the common packaging of narratives tied up with a neat bow. Real-life experiences regularly eschew the plotlines learned in English class; likewise, Robertson renounces the neat framing that contains an introduction, climax, and resolution. Especially the resolution. The stories vary in quality, though all are fully realized. In the second story, “Ship’s Log,” a young boy chronicles his attempts to dig a hole to China while peripherally noting his grandmother succumbing to Alzheimer’s disease. It’s a moving piece, but it suffers for its placement after the first, much more gripping, story. “Where Have You Fallen, Have You Fallen?” is a story told backward, about young love that feels like an early memory examined through the cloudiness of time. It’s memorable in a way the following story, “Roadnotes,” is not. A woman writes to her brother from the road as she meanders around the U.S. in search of understanding her recently deceased mother. Toward the end of the collection, the gripping postpartum-depression story “Slimebank Taxonomy” is lost amid the surrounding, less-impressive entries.

In short, the volume weighs down its better pieces: Stirring characters and heartrending experiences are diluted through their close proximity to each other and to more forgettable vignettes. All bleed into one another, so that the first story, by favor of its placement, is the only one that really sticks out. The collection’s diminishing returns affects the impact, too. Most of the stories center on people we’d rather look away from, namely the poor and the grieving. It’s all too easy to put blinders on when walking past a homeless person, just as being around those suffering the loss of loved ones can be so uncomfortable that it’s easier to ignore than to engage. Robertson puts what we’d rather not see on arresting display. It’s too bad it mostly gets lost in the mix.