Watergate isn’t the only frequency Francis Ford Coppola hit with The Conversation

The Conversation (1974)

Is it irony or just hypocrisy that Harry Caul, the professional snoop Gene Hackman plays in The Conversation, is obsessed with protecting his privacy? Maybe it’s neither. Maybe the guy’s just been doing what he does for long enough to know how easy it is to breach the firewall of someone’s personal life. Maybe a healthy supply of paranoia is just a side effect of becoming the “best bugger on the West Coast.” If there is an irony dripping off of Francis Ford Coppola’s suspense classic, it’s teased by the title itself: Harry spends the whole movie studying, dissecting, and decoding a single conversation, all the while remaining incapable of holding one himself. And it’s that failure, that inability to grasp the vagaries of human interaction, that causes him to miss a crucial detail—the most important clue—until it’s much too late.

The years have been kind to The Conversation. To say that it transcends the topical appeal it may have held upon first release is to acknowledge that surveillance anxieties haven’t exactly waned over the four decades since. And though the movie embodies much of what we’ve all come to cherish about ’70s American cinema—the moral ambiguity, the irresolution, the willingness to go downbeat in a way Hollywood never had before and hasn’t really since—Coppola’s understanding of alienation isn’t tethered to any one era. To that end, while The Conversation may look like the quintessential paranoid thriller of its decade, it also endures as a timeless character study, relevant so long as there are people with a knack for technology and a lack of social strategies. (Plant Harry Caul at a MacBook, and his prickly personality wouldn’t change, though watching him work would probably be less interesting.)

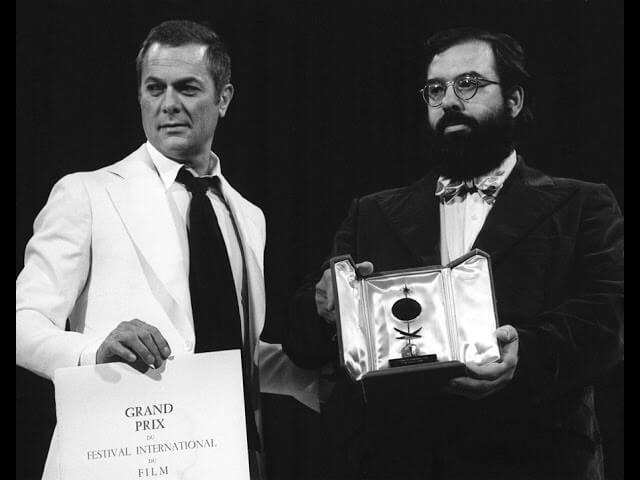

Has Cannes named a worthier winner? There are only a few in its league. The Conversation won the Grand Prix (not the Palme D’Or, which was reintroduced a year later) in 1974, a peak 12 months in the blooming career of its thirtysomething writer-director. This was also the year of The Godfather: Part II, which Coppola began work on before The Conversation was even finished; he ended up essentially losing to himself at the following year’s Academy Awards, as the blockbuster sequel picked up Best Picture, cementing his status as a giant of the industry. Coppola would next expend his clout, good will, and industry capital on Apocalypse Now, which clinched him a second top prize at Cannes five years later—the only time a director has won the festival twice in one decade. But that’s a story for a different piece.

The New Hollywood movement was making a splash on both sides of the ocean. At Cannes, Coppola bested no fewer than three fellow American mavericks: Robert Altman (in competition for Thieves Like Us, four years after his MASH took home the top prize), Hal Ashby (there with The Last Detail, for which Jack Nicholson won Best Actor), and Coppola’s soon-to-be-famous buddy, Steven Spielberg (whose Sugarland Express picked up Best Screenplay). Hackman, meanwhile, had starred in one of the previous year’s Grand Prix winners, Scarecrow, another New Hollywood export. But The Conversation’s roots can be traced further back, to a Cannes winner of a different decade and country: Michelangelo Antonioni’s arthouse sensation Blow-Up. Coppola essentially reconfigures and relocates that film’s plot, eavesdropping not on a London shutterbug with photographic evidence of a crime, but on a San Francisco audio expert who becomes convinced that the people he’s been hired to record may be in mortal danger.

The Conversation commences with the job already in progress, beginning with a famous telephoto establishing shot that immediately conveys an uncomfortable sense of surveillance. A slow zoom lands eventually on Hackman’s Harry, directing a team of technicians—perched on rooftops like snipers, shotgun mics in hand—to capture the private, intimate conversation of a young couple (Cindy Williams and Frederic Forrest) wandering a crowded, noisy Union Square. Two things stand out about this tour de force sequence. One is the guerilla shooting style of original cinematographer Haskell Wexler, who films like a peeping tom, catching quick glances of the “targets.” Wexler would spar with Coppola and eventually be replaced by Bill Butler, but his vérité-style contributions to the opening scene remain, clashing productively—especially during frequent flashbacks spliced throughout—with Butler’s less erratic approach. The second thing you notice is the complex, sometimes disorienting sound design by Walter Murch, who lets us hear the environment the way Harry does, complete with distortion and oppressive crowd noise. It makes sense that a movie about a sound guy would make sound design a priority, but Murch goes above and beyond; his work is crucial to shaping our (mis)understanding of events.

Unlike many of the other unheroic heroes of ’70s American cinema (including some played by Hackman himself), Harry isn’t “cool” or especially dangerous, except in the sense that his tapes could get you killed. He’s a standoffish, introverted weirdo who makes a living depriving strangers of what he cherishes the most, spends whole days listening to people talk to each other without picking up anything resembling a way with words, and alienates anyone who seems to give a damn about him. Tamping down the blustery charisma that was then something of a hallmark for the actor, Hackman makes Harry a fascinating mess of contradictions, pulling you in even as the character pushes everyone away. It’s a performance as quietly controlled as Butler’s camera movements, panning menacingly and sometimes mechanically across the film’s claustrophobic interior spaces.

The Conversation dispenses information about Harry in drips and drops, each new detail feeding into the last one. We learn that he’s excessively careful and secretive, calling from pay phones, installing three locks on his apartment door, and walking out on his girlfriend (Teri Garr) when she has the gall to ask simple questions about his personal life. We learn that he’s a Catholic when he chastises a longtime co-worker (John Cazale) for saying the Lord’s name in vain, then goes to confession for the first time in months. And though Harry takes a hard policy of indifference about what his clients do with the audio evidence he provides them, we learn that he harbors intense guilt about an old job that ended with a body count—a bit of exposition that explains the nagging uncertainty he feels when going over his most recent, completed assignment. (This is one instance where a revealing backstory really lends a character dimension, instead of simply feeling like a cheap motivational device.)

The only time Harry looks remotely happy is when he’s blowing on his saxophone—though even that has an element of bizarre perfectionism, given that he plays along with a recording. He does take a certain pride in his work: As in Blow-Up, it’s enthralling to watch this professional practice his craft, twirling knobs and adjusting levels to achieve the perfect mix. (It’s not a stretch to see the man as a kind of proxy filmmaker, especially given Coppola’s on-set reputation.) The most Harry ever speaks is during the scene where he brings some fellow buggers back to his warehouse and is goaded into bragging about the especially tricky gig that sets the plot into motion. This moment, more than any other, also showcases the fine supporting cast Coppola assembled—not just Garr and Cazale (in one of only five performances he delivered before his death, all in Best Picture nominees), but also a young, sneering Harrison Ford as the flunky trying to intimidate Harry and especially Allen Garfield, providing notes of tragicomic insecurity as a jealous competitor. This may be Hackman’s show, but as in Taxi Driver, another Cannes winner from a New Hollywood upstart, there are glimpses of a working-stiff ensemble comedy on the margins of the movie.

Is Harry right to feel apprehensive about delivering the tapes? Will he take this opportunity to atone for the blood on his hands and intervene before someone gets hurt as a result of his expertise? As a pure thriller, The Conversation is sneakily effective: Danger lurks in the depths of its narrative, expressed only in the main character’s unarticulated unease, until it comes bubbling up to the surface, like evidence of an unseen crime. The last act is a master class of suspense and dawning horror, offering proof that going prestige didn’t rob Coppola, who got his start directing the Roger Corman exploitation cheapie Dementia 13, of his skills as a nerve shredder. “Just because you’re paranoid…” is an old saw, but the genius of The Conversation’s final minutes is how they both refute and confirm Harry’s worst suspicions. Again, Murch’s subjective sound design plays a crucial role: One of the great reveals in suspense-movie history, the film’s brilliant rug-pull hinges entirely on inflection, on a single word and how it’s spoken. “I don’t care what they’re talking about,” Harry insists of his marks early on, but it’s his failure to understand the nature of their discussion—as opposed to the details of it—that leads straight to the movie’s nightmare climax.

Just as Blow-Up seemed to anticipate the conspiratorial fervor that would develop around the Zapruder film, The Conversation feels intrinsically linked to Watergate, even though it was in development long before the story broke. (That Nixon’s perpetrators used some of the exact same equipment as Harry Caul is what you might call a significant coincidence.) The film’s accidental relevance remains high in an age of wiretapping and unprecedented government surveillance; Coppola touched a zeitgeist that’s 40 years old and showing no signs of decay. Again, though, topical takes tend to drown out The Conversation’s true power. What Coppola achieved is a psychodrama about the dangers of being locked in your own private world, of slipping on noise-canceling headphones of any variety. Listening and hearing are not the same thing. Confusing one for the other can have dire consequences.

Did it deserve to win? Last time in this space, I wrote about what may be my least favorite Cannes winner, Maurice Pialat’s dour, unproductively difficult religious drama Under The Sun Of Satan. For this month’s edition, I decided to move to the other end of the spectrum and tackle what might be my favorite. In other words: Yes, The Conversation deserves all the acclaim René Clair and the rest of his Cannes jury granted it. Among the other competition titles I’ve seen, it’s rivaled only by Ali: Fear Eats The Soul, Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s tough, tender homage to the forbidden-romance melodramas of Douglas Sirk. Both films, incidentally, make fantastic use of tight indoor spaces.

Up next: The Silent World