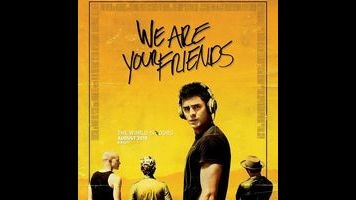

We Are Your Friends is as blank and empty as Zac Efron’s stare

Still in his nascence as a semi-adult movie star, Zac Efron has displayed an affinity for thinly sketched male camaraderie—dim bros who allegedly love each other’s company, but have very little to say to each other or anyone else. Neighbors made that desire for unchallenging friendship sort of touching, but movies like That Awkward Moment and We Are Your Friends place him in a dead zone that is full of bro signifiers and empty of actual friendship, leaning on his tendency to stare blankly instead of emoting.

To be fair, We Are Your Friends is only partially a bro-bonding dramedy. The DJ aspirations of Cole Carter (Efron)—and the more vaguely defined dreams of his trio of variously scheming, hustling, and drug-dealing friends living in the San Fernando Valley—position the movie as an update of ’90s youth-culture pictures like Trainspotting or, especially, Doug Liman’s Swingers and Go. Friends doesn’t need to live up to those movies to succeed, but it would have done well to harness their sense of urgency.

Director and co-writer Max Joseph—best known for holding cameras on Catfish—tries to oblige by augmenting a few sequences with on-screen text (usually redundant), rhythmic montages, and the occasional blast of invention, like a scene where Cole, inadvertently high on PCP, hallucinates paint bleeding off of an art gallery’s walls and enveloping partygoers. A less successful would-be set piece has Cole giving a tutorial on how to get people to dance at a party, a scene that deflates when it becomes clear that he and the movie are both mostly bullshitting. The movie flashes words and graphics, trying to sound like it’s actually explaining a process instead of contradicting its own pseudo-science and pseudo-math. Most confusing, Cole refers to the idea that a song’s beats per minute should mimic human heart rates as a “myth” seconds before saying that it is basically true.

A more energetic movie could power through this kind of earnest stupidity. But the tempo We Are Your Friends chases doesn’t come naturally to a lead character who often stands to the side of the action, bedeviled by constant requests to play “Drunk In Love” at parties and—like Vince from the Entourage movie—a crippling attraction to Emily Ratajowski. Unlike Entourage (which this movie, to its credit, can’t match in smug inconsequentiality), Friends doesn’t cast Ratajowski as herself; she plays Sophie, the personal assistant and girlfriend to James (Wes Bentley), a veteran DJ who takes Cole under his wing.

Before they meet, Cole describes James as someone who used to be good, but has gotten lost in lazy crowd-pleasing, but neither Cole nor the movie cares to elaborate any further on what makes his music (or, really, most music) particularly good or bad. James, a semi-functional alcoholic, maintains a low-key self-loathing that sometimes redirects to target the other characters: “You sound like an asshole. All that was missing was a hashtag,” he tells his mentee after Cole extols the virtue of a popular EDM technique. This admonishment alone makes him the most likable and interesting character in We Are Your Friends, even if his revelatory advice for Cole amounts to, “Hey, try using real sounds even if you’re creating electronic music.”

Sophie, meanwhile, offers barely more than a whisper of opinion about the music world she’s immersed in, beyond a few moments of damning Cole’s early work with faint praise. Even her dancing is wan, though the movie supposes that her tiny moves could help draw a crowd into a partying frenzy. (Throughout, music is portrayed as the playground of the attractive.) Ratajowski has a flat, almost affectless voice, from which the movie demands little; the conversations between her and Efron are astonishingly low content, even for people who have their big romantic breakthrough while high. The same goes for Cole’s buddies (Jonny Weston, Shiloh Fernandez, Alex Shaffer), emblematic of a world where characters speak in half-intelligible fragments and show off their realness by starting fights at the merest provocation.

By the time Cole reaches a point of self-reflection, even self-criticism, it’s too late; the vast emptiness at the movie’s center has become unintentionally funny. The story hinges on Cole’s ability to produce a melodramatic catharsis-mix EDM track, the genesis of which feels like a remedial introduction to pop music. (You mean music can be personal and danceable?!) As with Catfish, Joseph is there with his soulful handheld camera-bobbing, trying to convey the pensive thoughtfulness of a person who may not be thinking all that much. And as with Catfish, the audience catches on long before anyone on screen.