We fell in love with WALL-E because of how Pixar “filmed” him

With the world teetering on the brink of sci-fi dystopia, it’s perhaps a good time to revisit our imaginary post-apocalyptic futures. The 29th-century Earth of WALL-E presents one of the more memorable images of planetary decline. Mountains of neatly cubed trash rise higher that the decaying skyscrapers. Closer to ground level are the ruined superstores of the Buy-N-Large (BNL) corporation, which appears to have had a global monopoly on everything from mass transit to soda pop, and ads for BNL starliners that, centuries ago, whisked away the survivors of this profitably unlivable world. There isn’t a human in sight—only the last lonely robot, who continues to stack and sort garbage in a landscape strewn with broken-down clean-up bots of the same model.

It’s an unlikely place to open a family film, but then WALL-E is already steeped in irony by the time we reach those first glimpses of ruined Earth. The opening credits play over shots of space, accompanied by a song from Hello, Dolly!: “Out there, there’s a world outside of Yonkers…” As we’ll learn by the end of the movie’s opening sequence, the 1969 movie musical is just about all that’s survived of the better aspects of our nature, in the form of a well-worn VHS tape. Otherwise, it’s just a lot of trash, which is as captivating to a robot as archeological finds are to us.

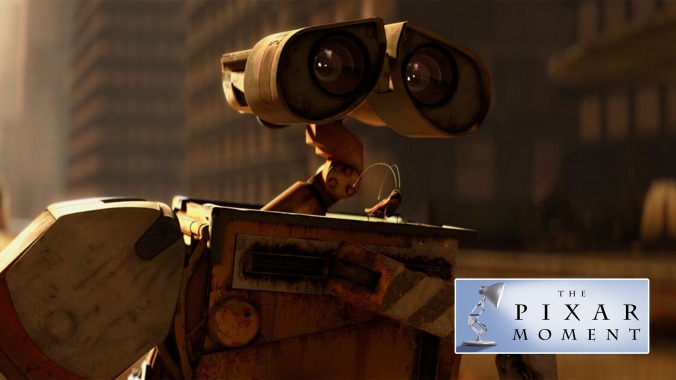

WALL-E, which was Pixar’s ninth feature, is for good reason considered to be one of the studio’s finest achievements. It immediately strikes a balance between the poles of sadness and whimsy that had by then already come to define Pixar. It’s also probably the best and most experimental showcase of its realistically inspired, on-model style of animation. In simplest terms, it manages to get viewers to identify with a character without a voice, mouth, legs, or elbows. WALL-E is mostly a box, and in theory, that’s about as inexpressive as it gets.

The larger part of WALL-E’s opening sequence, which runs about nine minutes, is spent following the robot as he finishes up a typical day. He putters on his tank treads past colossal machinery and an ancient superstore. (The movie is nothing if not a time capsule of turn-of-the-millennium concerns, not the least of which was a worry about the Wal-Mart-ification of American life.) He scavenges another WALL-E for spare parts. While the Cars series has always evaded the darker implications of a post-human reality, WALL-E’s slightly riskier sense of humor embraces them.

WALL-E rolls over newspapers and past holographic billboards that feature actual humans (including the late, great Fred Willard). Along with a clip from Hello, Dolly! that comes later in the sequence, this represents the first use of live-action in a Pixar film. WALL-E returns to his home in some kind of disabled transport; sorts through the finds of the day, including a spork and a Rubik’s Cube; looks up at stars that are briefly visible through a thick global cover of smog; feeds a cream-filled BNL snack cake to his only friend, a cockroach (in keeping with the old wisdom that members of order Blattodea and assorted species of Twinkie would outlive us in an apocalyptic scenario).

On the most basic level of storyboarding, this is great stuff. But what makes it work is a sense of scale, space, and atmosphere that goes well beyond matters of texture and particle physics. WALL-E’s long dialogue-free stretches and its focus on a non-anthropomorphic slapstick character are considered to be milestones in the history of the American animated blockbuster. But it is equally important as a tipping point in the development of simulated cinematography.

Lighting, shadows, and reflections are things that computer animation can always handle more fluidly than the hand-drawn variety. This is something that Pixar recognized from the start; however crude, the original Toy Story makes dramatic use of all three. Ratatouille, arguably the most modern-looking Pixar film, reached a new level of technical sophistication in its use of diffusion and depth-of-field. Nonetheless, it still employed a “cartoon” camera that was elastic and fluid. WALL-E, however, was the first computer animated film to successfully mimic live-action cinematography, from camera placement to the real-world properties of different focal lengths.

This was a process that involved tests with vintage Panavision lenses and consultations with Roger Deakins, whose chief advice was reportedly to simplify the lighting. The realism was a technical marvel in 2008. It’s why we can instantly gauge WALL-E’s size and the proportions of his surroundings, and why even the earliest close-ups of his binocular eyes appear so intimate. Not everything in the opening sequence of WALL-E is perfectly exposed; early on, there are shots with obvious hot spots, mimicking what a harsh wasteland sun might look like on film. Even if we don’t think we notice them, these subtleties are important to how we perceive WALL-E: Though he is the Pixar protagonist who least resembles an organic life-form, the movie immediately frames him like a human actor.