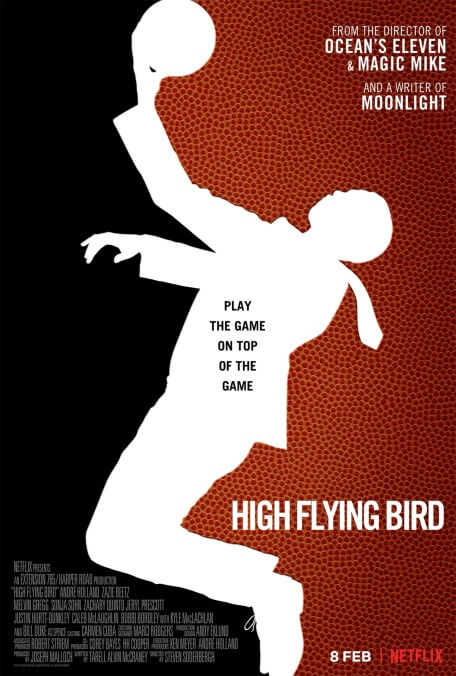

It takes guts, making a basketball movie with no basketball. Is there irony, too, in keeping players on the sideline of a story about returning power to the players? Steven Soderbergh has done both with his new low-fi Netflix drama High Flying Bird, which is interested in juking of a different sort—in backroom wheeling and dealing, not on-the-court action. (The one moment an actual game threatens to break out, Soderbergh cheekily and immediately cuts away.) This may be the closest we ever get to the director’s scrapped math-geek version of Moneyball, that $60 million data dump of a sports drama, which Sony pulled the plug on just five days before shooting was scheduled to begin. Here, though, Soderbergh is fantasizing about more than just loosening the stranglehold big spenders have on pro ball. He’s imagining a possible future without owners—a true reclamation of the game.

High Flying Bird is set during an NBA lockout, a protracted contract dispute that’s brought the season to a grinding halt, benched the talent, and dried up the revenue stream for everyone. Our window into this crisis, and into the sport’s shadow arena of politics and economics, is Ray (André Holland), a veteran agent with his back against the wall. The lockout has put the squeeze on his agency, which is hemorrhaging cash and clients, and Ray’s job is seriously endangered. They’ve even reassigned his loyal longtime assistant, the whip-smart and ambitious Sam (Zazie Beetz, from Atlanta and Deadpool 2), who’s still mostly in his corner—though the business will, occasionally, put their interests at odds.

Ray, who Holland plays with a sly mixture of sincerity and silver-tongued bravado, nurses a genuine political conscience—a resentment toward the way the NBA exploits the labor of young black athletes. (There’s a tragic backstory, a personal explanation for these feelings, that’s a bit underdeveloped.) But he’s also another of Soderbergh’s signature smooth operators, a slick and brilliant professional gaming the system, and High Flying Bird turns out to be a kind of shaggy heist movie, with a grand design (and payout) that’s only fully clear in retrospect. His livelihood at stake, Ray leaps into action, hustling across Manhattan to play multiple sides of the owner-player conflict. Part of this involves capitalizing on a social media beef involving a new client, the shit-hot rookie Erick (Melvin Gregg, who played a high school basketball star on the second season of American Vandal). Ray also crosses paths and trades fire with another star’s powerful mother/manager (Jeryl Prescott), the rep for the players’ union (The Wire’s Sonja Sohn), and an oily team owner (Kyle MacLachlan).

Whether wildly improvised or carefully engineered—it’s tough to say for a while—Ray’s master plan comes to involve a revolutionary rethinking of pro basketball: What if people would pay big bucks to watch stars directly square off, their head-to-head games broadcast like boxing matches? (That Netflix is one of the companies angling for the pay-per-view rights is a clever wink, more Bandersnatch-style brand integration, or possibly both.) This plot development mirrors the very structure of High Flying Bird, which unfolds as a series of one-on-one verbal showdowns. The script was written by Tarell Alvin McCraney, author of the play that became Moonlight, and Soderbergh can’t always disguise the staginess of the material—the film isn’t as fast and graceful on its feet as its protagonist. But McCraney’s shoptalk, alternately snappy and densely expository, is also heavy with insight about the imbalances and inequities of pro athletics. This is a movie with a lot of passionate opinions about basketball as a business.

For Soderbergh, it’s another DIY experiment, a chance for the director to play by his own rules. He shot the film on an iPhone 7, just like his last movie, Unsane. That psychological thriller looked cheap and ugly, probably by design: It reveled in its disreputability, finding a B-movie shorthand in the harsh and flat qualities of commercial tech. High Flying Bird is more polished and vibrant, more flattering to its motor-mouthed stars. There is also a sense and meaning in shooting this particular story from the vantage of a small, portable camera phone. Soderbergh understands how athletes’ lives are now filtered through the scrim of social media and viral video—and the film, rather optimistically, presents that same technology as a possible liberation, a way for the game’s stars to reclaim ownership of their own image through a platform not controlled by the corporate overlords of the league. Perhaps there’s a metaphor in there, too, about finding freeing alternatives to the Hollywood production model.

While McCraney’s plot keeps the focus locked on the suits and their mad scrambles, Soderbergh pulls one of his intended Moneyball tricks, cutting away to brief snippets of interviews with once and current stars of the game, like Reggie Jackson and Donovan Mitchell—a kind of Greek chorus, tossing around thoughts on what it’s like to live and work under the thumb of the NBA. At heart, High Flying Bird is another of the director’s films about the commodification of bodies, à la Magic Mike and The Girlfriend Experience. Whether that concern is compatible with its celebration of a big, juicy score may depend on where one lands on its hero, who’s a part of the very system (“the game on top of the game”) the film is implicating. Is Ray a prophet or just out for profit? Does he want to transform the sport or just save his own skin? By the end, Soderbergh has pulled off a kind of magic trick, bringing everything together in satisfying Ocean’s fashion while acknowledging that the underlying problem—the misdistribution of power in pro basketball—remains unsolved. If this is a heist movie, it’s one that leaves you wondering who’s really being robbed.

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)